Windows are a cheap, efficient and sustainable solution to fresh air and climate control in schools, once teachers learn to use them properly, says Andrew Mylius

You don’t need expensive fans or stacks to ensure schoolchildren get enough fresh air. Well-designed windows do the job equally well and for a fraction of the cost, as two secondary schools in Sheffield have shown.

First lesson after lunch: the classroom is warm and stuffy, pupils are struggling not to nod off and the teacher has to stifle a yawn. It is an all-too-familiar scenario that designers of a new generation of schools are trying to avoid.

Technical guidance has been redrafted and huge effort is being put into ventilation design to ensure that there is adequate fresh air and that classroom temperatures are neither too hot nor too cold.

“Looking at the existing stock of school buildings, in many classrooms, when the windows are closed, CO2 concentrations routinely go above 2000ppm,” says Eddie Murphy, technical director at Mott MacDonald. “The healthy maximum is 1000ppm, and CO2 concentration should never go above 1500ppm.”

Various pieces of legislation stipulate ventilation rates ranging from a continuous minimum of 3l/s per person to an occasional maximum 8l/s per person. To achieve these rates, designers are frequently incorporating fans into classroom designs. Stacks feature in some designs, taking advantage of buoyancy circulation to drive airflow.

Murphy, however, challenges whether fans and stacks are necessary. “While fans may help you to meet regulations for ventilation to the letter of the law, they emit noise so they make it harder to comply with regulations covering acoustics,” he says. “And fans and automatic stack control systems are costly, adding anything up to £6000 per classroom. Funding is limited not only for building schools but for running them. If you stick in lots of extra mechanical and electrical kit, you’re paying to operate and maintain it as well as install it. That’s money that could be going to enhance front-line education. Then, when you’re manufacturing, installing and running the kit, you’re also increasing your carbon footprint. Where is the sustainable thinking in that?”

Recognising the problems of poor ventilation design in schools procured under earlier private finance initiative (PFI) deals, Sheffield City Council specified stack ventilation for two third-wave PFI secondary schools ordered in 2004. Westfield and Meadowhead secondary schools were awarded to the contractor Kier with Mott MacDonald as consultant.

Funding restrictions meant, however, that the cost of building a design with stacks was prohibitive. Murphy seized the opportunity to demonstrate “all that you need are properly designed windows, placed in a well-designed facade”. Eliminating the stacks from the design saved £500,000 per school.

The windows used are 1180mm wide by 2m high and touch the 2900mm high ceiling. Vertically, they are divided into a 400mm high tilting pane at the top, a 1020 mm high pivoting pane in the middle and a 300mm high tilting pane at the bottom.

“The windows are tall enough to let in lots of daylight and drive effective buoyancy ventilation throughout the year. The crucial thing is that people must be able to open windows as much or as little as they need all year round,” Murphy says.

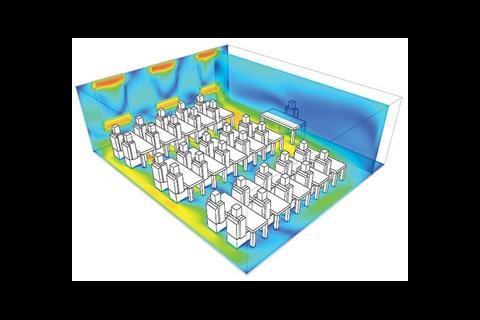

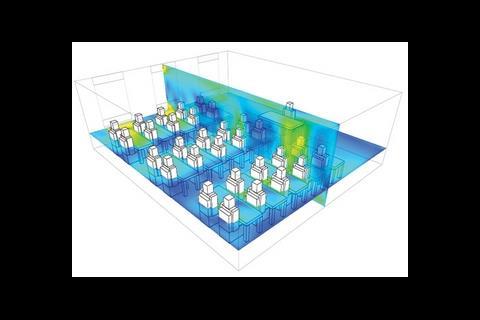

Each child in a classroom gives off heat equivalent to a 65W light bulb and each adult the equivalent of a 100W bulb. The columns of warm air rising from each pupil draw in fresh, cool air through the bottom of the windows, where it falls to the floor, while warm air laden with CO2 is purged through the top of the windows. With a couple of exceptions, there are three windows per classroom.

Thermal models of both schools were developed and possible trouble spots identified. “There were rooms with higher occupancy, rooms that were deep plan, and rooms with only two, rather than three, windows,” Murphy explains. Computational fluid dynamics modelling was carried out to explore in more detail how these rooms would perform.

To verify the CFD models, the testing specialist BSRIA was commissioned to carry out physical performance tests on the two potentially worst-performing classrooms in each school once they were completed, in January 2007. Temperatures and CO2 concentrations were found to be well within allowable levels, in line with modelled predictions. CO2 ranged from 900ppm to 1100ppm.

“What we predicted – and what we found – was that the classroom’s occupants drive the circulation system. The column of warm air rising from each person draws fresh air to where it’s needed,” Murphy says.

“And the system is self-regulating. When a class is over and all the children have left, the buoyancy system slows down so in winter you don’t come back in to a freezing room. By the same token, the greater the gain from solar heating, the greater the buoyancy driver that ventilates the room.”

Applying the radically basic idea of using only windows to ventilate a room requires understanding from staff and some common sense. A simple user guide has been drafted, setting out the ventilation philosophy and giving examples of how much window to open in different kinds of weather. “Teachers need to ditch the idea that if it’s cold outside, you shut the windows. They have to be open to a greater or lesser degree.

“Also, you need to leave a decent space between the window and the first desk so the child on the end doesn’t feel a draught. Provided you make that allowance, cool air will drop to floor level and disperse.” Any local chilling effect next to windows has been counteracted by putting radiant heating into the ceiling. “It feels like the warmth of the sun,” Murphy says.

There is a danger with buoyancy ventilation that when outside air temperatures rise, the “motor loses power”, he admits. The higher the temperature differential between air entering and leaving the room, the more effective the system is.

“In the summer, as the outside air temperature approaches the same level as the inside air temperature, the convection current slows down and can stall. On a calm day, even with windows wide open, there may be relatively little air exchange.

“We were concerned, “Murphy says, “and modelled the number of hours where the system would fall over. Based on average annual weather patterns, it turned out to be less than one hour per year,” he says. “So I don’t see the value in spending huge amounts of money on fans or stacks to achieve the prescribed ventilation value for that one hour. This shouldn’t be an M&E problem. It comes down to proper facade and window design.”

The same approach is being applied by Mott MacDonald on current projects in Sheffield’s Building Schools for the Future programme – where, once again, funds are tight.

BSRIA carried out tests at Meadowhead and Westfield schools in January 2007. In the two worst-performing classrooms at each school, BSRIA installed 32 metal cylinders, one at each desk place to represent a child, plus one at the front representing the teacher. Each cylinder housed a light bulb rated at 65W for children and 100W for the adult, giving off heat equivalent to a full class. Carbon dioxide was released from multiple points to simulate exhaled CO2.

CO2 levels were monitored in the classroom and in the corridor outside over the course of a full school day. Periodic checks were carried out and windows opened or closed to varying degrees to maintain a comfortable temperature.

Testing at each school lasted a week. The weather conditions were windy during the Westfield testing week and calm while tests were under way at Meadowhead.

BSRIA reported that there was no problem in meeting the minimum 3l/s per person ventilation requirement stipulated in Building Bulletin 101 Ventilation of School Buildings. At no time did CO2 concentrations exceed the maximum allowance of 1500ppm. Concentrations averaged 900-1100ppm throughout the week-long tests.

A note of caution was sounded by William Booth, BSRIA’s head of site investigations and physical modelling, because the tests were carried out in winter. Cold outside air temperatures and windier weather promote a high air exchange rate. But feedback from Kier’s facilities managers after a year of operation confirms that the ventilation strategy works in summer as well.

Source

Building Sustainable Design

Postscript

Andrew Mylius is publications editor at Mott MacDonald

Original print headline 'Back to basics'

No comments yet