Brian Mark and his wife set out to redevelop a Surrey site with sustainable ideals, but found the process far from straightforward. Stephen Kennett hears their cautionary tale

You can pretty much predict how an episode of Channel Four’s Property Ladder will unravel. An inexperienced couple will confidently launch into redeveloping a property – only to discover that things are not quite as straightforward as they appear. As the costs begin to spiral and the construction program begins to slip, the only certainty is they’ll ignore the advice offered by the presenter Sarah Beeny.

You might expect, though, that the founding partner of one of London’s foremost building services consultancies and his wife – a water and waste consultant – would have a better chance than most at the property development game.

“Well, looking back, naming the project Bliss was probably asking for trouble,” says Brian Mark ruefully. “It was in no way blissful.” Bliss, or Beacon Low Impact Structures and Services, was the company that Brian Mark set up with his wife Gwen and two friends in May 1998 to develop a site in Kingston upon Thames. What followed constitutes a sobering lesson for any would-be developer.

The Marks never set out to be property developers. According to Gwen, it came about by accident. “A good friend of ours, who I’d worked with at the Kingston Green Forum – a local forerunner of Agenda 21 – was living in a community house and wanted somewhere to move in with his girlfriend,” she explains.

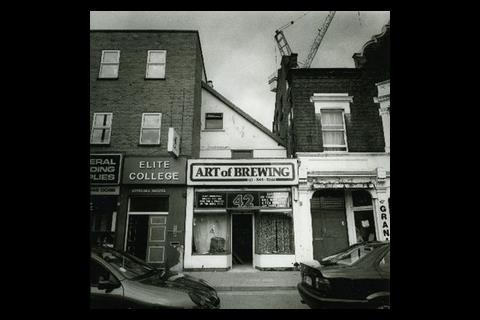

As it happened, the lease on the building housing the Green Forum was coming up for renewal around this time and the owners, The Higgs Trust, had decided to sell the property. The site included a collection of buildings, but one in particular – number 42A – stood out. It was the only Victorian building left on the road and had been built by a chemist, Alfred Higgs, in the 1890s. “It was an extraordinary example of Victorian engineering,” says Brian. “For example, the basement, which was used as a laboratory, was built from three different grades of limestone to make it watertight.”

It interested Brian Mark for another reason, too. Like many Victorian shops, it had been built with a large yard behind to accommodate the horses and carts that would have originally serviced it. These sites, although common in Britain, are usually viewed as undevelopable because they are fragmented and access is difficult. “I wanted to find out whether you could develop them and make money,” says Brian.

The original shop over the basement was being used by an electrical wholesalers, but above this was a large three-bedroom flat, complete with marble fireplaces and a winding mahogany staircase. “We came up with a business plan whereby we’d form a partnership and rent out the two shops, while our friends would get the flat above the shop to live in and we’d redevelop the rear of the site,” explains Gwen.

The Higgs Trust agreed to sell the site to BLISS and in July 1998 the deal went through, with the Marks putting in £260 000 and their friends investing £50 000.

The original plan: offices

For the next two years, things went to plan. Tenants were found for the shops, but for the business case to work, plans for redeveloping the rear of the site had to move forward. The initial idea involved building an office block that was passively cooled by using Termodeck combined with a flat roof flooded with water. Exposed to the night sky and shaded from the daytime sun, the water would chill and this could be used to cool the building with minimal energy requirements. “I thought the best way to see if it would work was to build it. It was going to be a research project,” says Brian.

Planning permission for the office block came through in April 2000 – and this was when the reality of being a property developer kicked in. “At this point, it became clear that there was a glut of office accommodation in Richmond and that letting the space was going to be a real issue,” reveals Brian.

So it was time to switch tracks. The plans for an office block were shelved and a decision made to develop the site for housing instead.

As if this wasn’t enough, a breakdown ensued in the BLISS partnership in the meantime. Initially, the Marks agreed to sell their 84% share of the business, thinking this was the easiest way to move on. However, when their former friends couldn’t raise the capital, they agreed to sell them the flat they were living in on the understanding that the rest of the site would still be redeveloped. Despite this, the couple’s actions held back the granting of planning permission until February 2004. Work finally began on site the following December.

Looking back now, naming the project bliss was probably asking for trouble. It was in no way blissful

The next phase: flats

While one surveyor managed to squeeze 12 one-bed flats onto the site, the Marks – wanting to create a pleasant environment for residents – opted for a design by Lawray Architects with four flats in a three storey flat-roofed building containing living spaces linked to a two storey block containing bedrooms.

The initial design included floors and roof made from hollow core concrete slabs – something not tried before in a residential building. Cooler, summer-night air would be drawn through the hollow cores using the coolth stored in the solid mass of the plank as a buffer, smoothing out the peaks and troughs of annual and diurnal temperatures to create a low-energy, comfortable living environment.

The design included two other novel ideas. One was a centralised community heating system that recovered heat from the waste domestic hot water. Coils connected to heat pumps would be wrapped around the clay drainage pipes in turn surrounded by concrete to act as thermal mass and absorb the heat of hot water from baths, showers and washing up that would otherwise be wasted. This was difficult to monitor, but would act as an experiment to see what benefits it might offer.

The second idea was dynamic insulation – an idea used by Gaia Architects in the McLaren Community Leisure Centre, Callander in the Trossachs, Scotland. This draws on a technique used to construct animal sheds in Sweden where winter temperatures drop to -25°C. Essentially, a mechanical ventilation system is used to ventilate the sheds but rather than simply exhausting the warm air, it is drawn out through the insulated walls, helping to prevent heat loss.

The plans were drawn up, quotes obtained and the project costed. “Then the QS told me: ‘if it all goes perfectly to plan you’ll make £134 profit’”, recalls Brian. “That’s when I had to do what developers always do to me and strip all this stuff out.”

Although it was back to the drawing board, it didn’t mean the building couldn’t still be pioneering in its own way. “Everything I do here is an experiment for a bigger thing,” says Brian.

The reworked scheme now under construction uses straightforward blockwork cavity wall construction with block and beam floors. Enhanced wall insulation brings the U-value down to 0.23 W/m2K, while the outside is clad in locally grown coppiced sweet chestnut from a nearby sawmill. High performance timber windows from Norway - they were twice the price in the UK - provide a U-value of 1.6 W/m2K, considerably better than 2002 Part L.

Each flat has a mechanical ventilation system, partly to overcome its urban location and the effects of PM10s and also to cut down on energy – each system is installed with heat exchangers to recover 60-70% of the heat from exhaust air with control provided by room CO2 sensors.

The idea is that when the building is completed, the flats will be sold on long leases – but written into the contract will be a clause that each flat agrees to take its share of the freehold in a year’s time. “This is because I want to spend a year optimising the building and finding out how it performs and then I never want to see it again,” grins Brian, half joking.

One of the inherent issues with large-scale residential developments he wants to tackle is the use of solar thermal collectors. Although these are one of the most economic renewables, the problem with a multi-storey building with a limited footprint is to ensure everyone can benefit? The obvious answer is a communal heating system, but this brings with it meter reading and billing issues, with no landlord this could become a problem.

Low-energy solutions

On Richmond Road, the solution has been to install a 15 m2 installation of solar collectors which feed a landlord’s pre-heat hot water cylinder. The incoming mains water supply splits, supplying each of the flats as well as the cylinder, where it is preheated before being piped separately to the gas-fired combi boilers installed in each flat. “I’m embarrassed at having installed boilers,” says Brian. “But ultimately the solar collectors should provide up to 50% of the domestic hot water.”

The QS told me that if it all went perfectly to plan I’d make £134 profit

The system operates off mains pressure and is a cheap way of providing a communal heating network under PPS1, despite it being a single pipe system. “We’re already using it on much larger projects because it is so much cheaper to put in and manage,” says Brian.

Each flat will be provided with an electricity supply via check meters from a single centrally metered landlords supply. The leases will be drafted placing a responsibility on the landlord – and after a year, the tenants’ association– to source renewable electricity from a Renewable Energy Guarantee of Origin (REGO) supplier.

Other features built into the design include a 3000 litre rainwater storage tank that will collect rainwater from all the downpipes. This will be used for toilet flushing and, as part of the overall water management design, each flat uses low water twin flush wcs, low flow shower heads and low water capacity baths.

Each flat will also be provided with purpose built recycling for the separate collection of paper, metal, plastics and glass and a bay will be set aside outside for their collection and storage and another for biodegradable waste.

So would the Marks do it again? It’s fair to say the experience has been stressful at times and something of a learning curve, especially given that they haven’t just opted for conventional solutions. “It’s a little bit worrying that we’re the guinea pigs,” says Gwen. “But we’ve only ourselves to blame for that”.

As well as the usual funding worries, there have been other problems that would have tried even an experienced developer. These include the neighbouring development building having its foundations over the site boundary with the result that when it came to setting out the plans no longer fitted the site. It was decided that cutting into the foundations was not an option. “We swivelled our building to get it to fit but they had to cede a piece of their site to make it possible,” says Brian. “They’ve also been very helpful in giving us access”.

Despite building in the winter months there were virtually no days when building wasn’t possible and construction is on programme. Brymans DBS are currently doing the services installation and so far so good. “They’re a brand of thinking electricians and plumbers who aren’t phased by the innovation and seem to be enjoying it,” says Gwen.

Currently there are hold-ups on the delivery of the windows and the installation of the ductwork for the mechanical ventilation but construction should be completed the end of the year when the flats will go on the market.

“The biggest problem,” says Gwen, “is that we have no idea what the flats are worth. There is nothing comparable in Kingston [in terms of low energy developments] to provide a guide as to their market value.”

That said, talking to local estate agents the feedback has been positive. “Buyers like gated developments, which effectively is what this site has given us,” says Gwen. “But I think we need to find the right estate agent to put them on the market with.”

Taking into account construction costs, design fees and servicing the loan, Brian estimates they might make £400,000 on the project. The biggest unknown is the land value, which given the poor access would be almost valueless. “Whether or not I’ve proved that these type of sites are suitable for development is debatable. It would probably work if you could buy, say, six shops and demolish one to give good site access.”

The Marks wouldn’t rule out doing it again, but say it probably won’t be for a few years yet. “If there’s one thing that’s come out of this,” says Brian, “it’s that I have a new found sympathy for developers.”

Source

Building Sustainable Design

Postscript

Brian Mark is partner of Fulcrum Consulting. He will be speaking about his experience as a developer on 11 October at M&E, The Building Services event. For more details, visit www.buildingservicesevent.com

No comments yet