Can the dirt, grime and decay of industrial sites provide a good basis for mixed-use development? Josephine Smit finds out

Paintworks, Bristol - Verve Properties

Project

Ashley Nicholson had an ambitious plan. The director with developer Verve had around 80 projects to his credit, some commercial, some residential and almost all involving reviving old buildings in off-pitch locations. At Paintworks, he set out to apply all his knowledge to produce the perfect regeneration, create a model of best practice, and set out Verve’s stall as a developer of “heart and soul”.

The 12-acre site was an industrial estate packed with dull industrial buildings of varying ages. A combination of conversion and new build will produce a mixed-use village of around 277 homes and live/work units alongside business units housing everything from a sculptor to a dentist. The site also has a 59,000ft2 studio for television production company Endemol West. The developer has worked with architects Tooley and Foster and Acanthus Ferguson Mann, contractors Greenhill Regeneration and Bilton and Johnson, mechanical and electrical consultant Silcock Dawson, engineering consultants FMH Consulting Engineers and Engage Consult and project manager Strebor Management.

Phase one comprises 20 apartments and live/work units and 32 business units, plus a bar/cafe and gallery, all conversions and now complete. The first element of phase 2 was completed this year and delivered 15 business units. The second element of phase two, refurbishment of a 1930s-built administration building into seven apartments and seven business units, will be completed next year. The developer has applied for outline planning permission to develop the third and final phase of around 250 new-build homes with more commercial space and a piazza. Homes are sold as loft-style shells at prices from £125,000.

The brief

Nicholson is more interested in creating environments that work than architectural statements, more interested in the little man than big business, and, in case you hadn’t got the message already, anti-corporate. This is regeneration with attitude.

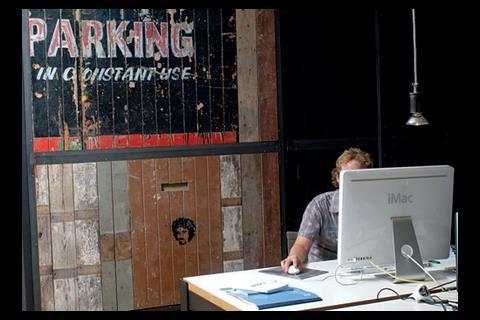

The brief was unconventional. Nicholson wanted perfection in community and regeneration terms, but not aesthetics. He says: “At first, the architect architecturalised it. I didn’t want everything squared off. We were terribly hands on. We wanted it designed from how it would work, who would use it, mixing uses to provide natural surveillance.” The end result is a scheme that is medieval in its compactness, and which Nicholson describes as “really raw”.

Feedback

If the planners had got their way, Paintworks would not have been a mixed community. The developer paid cleared warehouse values for the land five years ago, but the site’s hillside location made it difficult for articulated lorries to access and Verve would not have made money by letting the warehouses.

Although residential seemed a natural use, the developer’s first planning application was E E to create a hub for small businesses. Nicholson was taken aback by the planners’ reaction: “They said, over our dead body will you get any housing on this site, although we hadn’t mentioned housing at that stage. We always thought this site was perfect for mixed use and we got there. All we’ve done is use the airspace above the business units for housing.” The scheme has no shops, because the planners did not want competition with existing retail; instead there are “make and sell” units.

The retained rows of Victorian sheds make for a far more inviting place now that courtyards and alleyways have been cut into them to create more external space, and coloured renders, bold graphics and big windows have been added. The apartments’ only private space is at balcony or rooftop level, while the courtyards are lined by doors that lead to homes, businesses or both.

The rawness of the scheme is accentuated by re-used materials. The bar’s counter is made from old doors, gabion walls have rubble fill, and second-hand cattle troughs will be planters for a communal roof garden. Nicholson went so far as to ask the contractor to put their worst plasterer on the job of putting an authentically rough Mediterranean-style finish to external walls.

This is not speculative because we know our market– we might be appealing to 20% of the overall market, but we'll pick up 80% of that 20%

Ashley Nicholson

Nicholson’s counter-culture has won over the council: “The council wrote a report on creative industries and took ownership of the scheme. Now they’re massively behind it.” The council has good reason to be supportive: before development the site was a derelict eyesore and employed just 30 people. Now it looks slightly alternative with its wiggly-lined zebra crossings, the bar is buzzing on a Saturday night and the number of people employed on site, 750, will double by completion.

One battle Nicholson cannot win is with legislation, which is an ongoing source of frustration for the free-thinking radical. “I reckon 65-70% of my time is spent fighting the grown-ups – things like the Disability Discrimination Act and building control. The system is discriminatory against the guys with the least. We provide cheap space, but the system makes it difficult,” he says. He is particularly vexed he couldn’t use the cobbles he wanted – not red ones next to a red brick wall “because the visually impaired would not be able to see what was what”; none at all allowed on pedestrianised alleyways – it would be “a trip hazard”.

Occupants are chosen with care. “So far we’ve been able to be picky,” admits Nicholson. “I’ve met everyone here, in the commercial and residential. We wouldn’t let investors in. We knew we needed creative energy to kickstart this.” Accountants and mortgage brokers were rejected; the dentist and hairdresser got the nod. Community value wins over cash.

Nicholson’s ultimate project has, he says, taught him fortune favours the brave: “Everyone said this wouldn’t work, but it has. Housebuilders and commercial developers say you can’t create communities, but this proves you can. The deterrent is that it is hard work, takes effort, input and desire.”

The scheme proves a point or two for Nicholson. “There is so much crap development around, driven by people interested in money and brands. Mass market housebuilders are machines where product is more important than people. The commercial sector is driven by the need to get institutional funding.

“I wanted this to be ammunition for planners. They get bullied by housebuilders and commercial developers on why it is not possible to do something. This site would have been either wriggly tin sheds or dull flats. We hope this will become a seamless part of town.”

Nicholson may think Verve can do better than mainstream developers but he has no qualms about selling the third phase site to them. “We’re a small company and lack the procurement to deliver housing. We accept the limitations of housebuilders but push them our way to produce a workable solution. We’re being pragmatic.” Verve will retain control over design and investor sales levels, and Nicholson says it too will be a sustainable community: “There will be mews, arcades, deck walkways – which have been badly represented. You can introduce all the elements here into new build. And there will be humour to show it is not sterile.”

Kelham Riverside, Sheffield Raven Group

Project

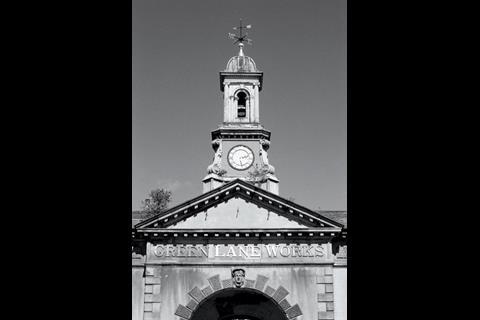

Sheffield’s Kelham Island on the River Don has the perfect heritage ingredients: the traditional Fat Cat pub, a museum charting the history of the steel industry, and a miscellany of industrial buildings.

This is an area of ongoing regeneration, and Kelham Riverside is the latest manifestation. The scheme in fact comprises two sites, sitting either side of a mill race, or goit, and has an illustrious history as the home of the heavy industry of steel rolling mills.

The sites include some fine redbrick Victorian buildings that are being retained, including a Grade I-listed gatehouse, a formal square of workshops and an elephant house, built for the elephants that once lifted the steelwork. But much of the land was covered by 1950s and 60s built sheds that are now being demolished. In their place, more than 400 homes are being developed, alongside commercial premises including offices and bar and restaurant space in buildings up to five storeys high. Under the project, the development team is also restoring the goit, which becomes the centrepiece of the scheme.

The island is already home to a highly regarded residential conversion, Cornish Place and Brooklyn Works. That was developed just over a decade ago and was at that time a pioneering scheme, featured in the government report, Mixed-use development: practice and potential. Many of the same people who worked on that scheme are also behind Kelham Riverside, with developer Raven working with Axis Architecture, contractor Mansell, structural engineer BSP Consulting, and project manager and cost consultant EC Harris. Landowner was Miba-Tyzak.

We are putting mobility access homes in the new build. That would have been very difficult to do in a converted factory

Kevin Seers

The first phase, which is under construction, comprises 15 refurbished homes, including two houses being created from the elephant house, plus 130 new apartments. The 380-unit second phase includes 90 refurbished homes and is expected to go on site next year.

The brief

Raven Group director Clive Wilding says the aims were simple: “We wanted to make the best use of what we’ve got. Old industrial buildings sell well because of their quality of space and light. We learned from Cornish Place that simplest is best. Fussy things don’t work on industrial buildings.”

Although the scheme sits within an industrial conservation area, the new buildings were not intended to copy their Victorian neighbours: “The new build replicates features of the old, but you can’t do pastiche,” says Wilding. Kevin Seers, director with Axis Architecture, adds: “We’ve had long discussions with English Heritage and they are adamant that they don’t want crude copies of old buildings; they want good contextual modern buildings and good quality restoration.”

There is one exception to this rule. In the second phase one building is to be replicated to re-form the long-demolished fourth side of a square of Victorian workshop buildings.

Feedback

Cornish Place and Kelham Riverside might be separated by more than a decade in time, but some of the learning from the former is being applied to the latter. Both schemes pose challenges, says Wilding, in understanding the existing structures. “At Cornish Place cleaning up the building resulted in some efflorescence of the brickwork, so we told residents that occasionally when they were hoovering the floor, they should hoover the walls too. You go into old buildings thinking that you know what is there, but often you don’t.”

The new buildings refer to the heritage context in their use of industrial-style materials, including red brick, zinc and planked oak. The architect has also picked up on traditional industrial features like northern lights, the large north-facing windows that factories were equipped with to ensure there was enough daylight for working processes without letting in bright sunlight. “We have used them to create a sawtooth roof, evoking the industrial heritage,” explains Seers.

The challenges of bringing old buildings into line with present day regulations appear to be universal. Seers says: “It is difficult, but it helps if you have got several hundred new build units alongside, as then you can offset some of the legislative problems in the new build.”

“If you are working in a conservation area it is a question of what takes priority,” says Wilding. “At the beginning you need to set out what the objective is and try to be sympathetic to that, but it requires all agencies to understand the principal objective: to retain a lovely old building.”

Making the existing buildings environmentally friendly by adding green technology is a challenge that is not yet being faced by this project, but one environmental issue cannot be ignored. When floods hit the UK this summer, Sheffield was severely affected and the Kelham Island museum remains closed because of damage to exhibits. Existing buildings on the site have been surveyed and extent of the flooding marked, says Seers. “Water came part way up the buildings. As a result, we are looking with the Environment Agency at flood wall defences.”

Irrespective of the flooding, the first phase of new build homes has sold out ahead of completion, and the scheme looks set to follow the lead set by Cornish Works, where homes have quadrupled in value since they were built. Industrial buildings can make good residential conversions for a number of reasons, says Wilding. “They have character and they are often in interesting locations, often beside water because they needed it for industrial processes. They are often built on a more structural basis and have big windows for natural light – and the space is easy to convert.”

Still, a long time has elapsed between the two schemes, a factor that Seers explains: “The first buildings to be refurbished at Kelham Island were the buildings at risk. Then there was a lull of several years, but now industry is moving elsewhere and bit by bit sites are freeing up. Most of the sites coming through now are new build and have no real potential for conversion. We’re now finding that it is a matter of mixing new with old.”

Products used

Cobbles: Bradstone carpet stones

Windows: Cotswold casements for Crittall replacements. Solaglas and Bristol Window Company for new aluminium

Render: Alsecco

Source

RegenerateLive

No comments yet