It is the latter that Rogers believes has so far failed to impact on the UK market. In contrast to Asia, the uptake of integration between the separate controls systems within buildings has been under exploited and the biggest barrier to this stems from the way buildings are designed and built. "One of the reasons is we still work by disciplines," says Rogers. "The building design is split up and those disciplines go away and design silo systems". The upshot is five or six head ends for each different, and often proprietary, system.

Integration at this stage means extra cost to the client, but the benefits for both building users and operators can make the price worth paying. "It's got to be sold on benefits, there is no point integrating unless it's a benefit to the client," adds Rogers. "For a lot of buildings clients are happy to have separate systems so why bother?" For others there are obvious advantages to be had from integration. Energy management is a traditional driver, but where it truly comes into its own is with large multi-purpose facilities typically airports, hospitals and universities. The reasons can largely be put down to the constant movement and flow of users in these facilities, compared to the relatively static environment encountered with staff in offices.

Gate allocation at airports is a classic example. Typically used for short periods, these spaces allow cost and energy saving benefits to come from feeding information from the building services sub-packages, such as the lighting and hvac, into the main management system along with flight information from the master airport control. The running time of air conditioning plant and lighting can be reduced by programming it to turn on when a particular gate is required, and off when the area is vacated and the flight departed. In this way only those areas that are occupied will receive full air conditioning.

The key to overcoming the barriers for better integration is to get on board in the early stages of design believes Rogers, allowing the controls engineer or system integrator to design for integration from day one. Ultimately somebody has to tie the various systems together, but early involvement can help reduce duplication in the various silo packages, whether it is monitoring and metering devices, or public address systems that can be used for emergency evacuation or electronic signage. The resulting savings can then help offset the cost of integration.

"Open systems like Lon have gone a long way to integrate what I'd call the products," says Rogers. But there are drawbacks. One, even with hundreds of products there will probably never be the point where every system you want to integrate will have Lon products available to do it. Two, binding these products together still involves a lot of engineering. "For certain areas of the subsystem it's great and for the client it's good because he's not tied to any one supplier. But it's not the only answer.

"I think you'll find especially on the bigger projects IP addressable systems will probably overtake Lon based anyway but again it's not fully there yet. There are a number of IP addressable systems working on common structure cable systems and the growth in that will accelerate."

For now when most people talk about integration they still want separate local area networks for systems such as hvac and fire. Getting information from each subsystem into a common overall management system is achieved using OLE for Process Control (OPC). "We're pushing this on the bigger projects. Individual subsystems function on their own but they are integrated at the management end," explains Rogers.

The head end of each subsystem acts as a server – allowing a laptop to be plugged in for maintenance – and communicates via an OPC driver to the head end management system. This collates data from all the other subsystems, acting as a viewing platform with facilities to support pdas and other devices.

Enhanced reporting

Integration can also enhance management reporting and encourage better maintenance. One public transport operator uses bms technology to monitor the performance of the company contracted to clean the smoke detector heads in its passenger train tunnels. The system indicates when the heads need cleaning and if any have been accidentally missed, and is also tied into the payment system, whereby the contractor is paid only for the heads that have been cleaned. This flows onto other areas. With maintenance contractors often tied to performance related contracts – relating to call out times or down time – accurate management reports can be used for validation, and subsequent payment.

In many ways the Arup designed City of Manchester Stadium is a good example of an intelligent building. Its inherent adaptability guaranteed it had a useful life well beyond the 2002 Commonwealth Games. Now home to Manchester City FC it is also using a smart card ticketing system for season ticket holders. "One of the biggest areas of intelligence coming is the access/security side," says Rogers. But it goes beyond just entry systems. While Man City fans can pre-book seats and not worry about queuing for tickets, the potential of smart card technology goes much further. The Octopus card in Hong Kong was designed as a ticketing system for the local underground and was subsequently extended for use on buses, ferries and taxis. Potentially this could become an access card for the holder's apartment, offices or university complex. Linked with a truly integrated building it has the potential to monitor occupancy and traffic flows within a building and vary internal conditions accordingly. Arup is pushing to use similar technology on its design for Beijing's Olympic stadium to track the movement of athletes and official throughout the complex, preventing them from missing events and even providing them with a cash-less e-purse. Today China, tomorrow the UK?

The price of integration

As an advocate of the LonMark approach to open systems, Paul Mason sees the adoption of integrated systems within buildings as a way to improve how buildings are procured, constructed and run. The barriers to change are similarly entrenched in the procurement process. “The key point for me was always getting it to work,” says Mason. “Things don’t work at the moment. The natural response is let’s just do it the traditional way.”The challenge for open systems is to improve the adaptability of the system, remove lock-in, reduce the risk in the controls element and lower costs. On paper, Mason’s answer is straightforward. Don’t treat controls as a system but consider them as commodities hooked up to a wire. “The only way to manage this is to horizontalise the system components into traditional packages and then employ a network integrator to link them horizontally. The traditional approach is to buy vertical, end-to-end disintegrated systems.”

This means the m&e contractor can use its buying power to purchase the equipment, install it when in the schedule it needs to and then leave it to the integrator to link the various controls together and make sure they work. By bringing the integrator on board early and employing them directly through the main contractor makes them well placed to provide support at management level. They become responsible for the general systems integration including understanding the scope of the installation, detail designs responsibility, checking the installed cable and equipment, and user interface requirements, bringing with them a vested interest in making sure the design can be integrated as easily as possible.

Cost is a major issue and it is here that Mason is adamant that integration has an advantage. Taking the 2: 20: 200 ratio for capital cost, lifecycle and staff cost respectively. “We’re all focussed on the two,” says Mason. “If it became 2·1 would that really in the great scheme make a huge difference especially if it allowed your 20 to become 19.” In theory no but in reality no-one is going to spend more money than they need even if it is an intelligent building. “I say, I can guarantee you a 4% saving on the whole m&e if you went full out you might get 8%.” But saying this and proving it are two different things and clients willing to publish the true costs on a project are few and far between. Rather than hold out indefinitely for such a client Mason has taken things into his own hands and designed a building which he can own and then make freely available for use in the public realm as a cost comparison of systems and solutions. The project incorporates Mason’s philosophy, engaging the whole supply chain to achieve accurate costing while developing benefit from new technology and ways of working. It was also designed to reduce risks for all those involved, improve accountability and reduce costs.

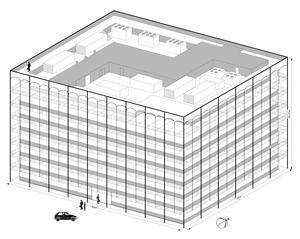

The virtual building is a typical office development. The eight storey 11 000 m2 building is compliant with current Building Regulations and British Council for Offices specifications. Mason has taken his design to RIBA Stage D. The building has an 80:20 nett to gross floor area and encompasses all the trappings expected of a generic hq office.

The initial scenario compares the cost of a traditional conventional proprietary standalone controls compared to an integrated interoperable open system based on an IP web-server backbone system with a LonMark system at the sub network. All the building services systems are fully integrated, including the fire system, which is supported on an independent network. The Lon/IP open system solution provides complete data sharing through LonMark Interoperability products whereas the proprietary systems are each independent and have their own head ends or panels. Interoperation by the proprietary systems is by volt-free contacts as appropriate.

Turner & Townsend Cost Management took the specification away and carried out an independent cost comparison of the two systems based on current rates. Pricing is conservative claims Mason to ensure even handiness. Product manufactures are listed and cost manager’s notes included detailing the interpretation of the spec. Both the traditional and the Lon solutions are run side by side to highlight where the differences occur. The outcome of this was a 4% saving on capital cost, amounting to £323 000.

Further verification is also in the pipeline. Mason has recently finished a scheme for the Department of Constitutional Affairs in Petty France, London. The finished building is virtually fully integrated except for the security system and Mason is hopeful of using the cost information from this scheme to cross-reference it with the virtual building study.

The Lon road to interoperability

Launched in February LonMark International has been created to overcome some of the shortcomings of the former LonMark Interoperability Association.The new trade association will now be independent from Echelon and will be responsible for administering, developing and maintaining technical design guidelines and standards. It will offer a complete, off-the-shelf networking technology platform for designing and implementing interoperable control networks. In addition it is working on a web-based tool that will allow member companies to self-certify products, thereby saving time getting products to market.

The association is now divided into three regions, the US, Europe and Asia, each with equal voting rights on the international board and its own task groups who provide a forum for members to develop the functional profiles that define the scope of products and systems.

Source

Building Sustainable Design

No comments yet