High-density housing conjures images of the nightmare slum tenements seen in some other global cities, but can modern design make high density attractive in the UK?

In her 1961 book ‘The Death and Life of Great American Cities’, American urbanist Jane Jacobs identified density as one of her four key ingredients for thriving and diverse cities – contrary to academic theory at the time. She wrote that in order for cities to work, “there must be a sufficiently dense concentration of people, for whatever purposes they may be there. Crucially, this includes a dense concentration in the case of people who are there because of residence.”

Over the past two decades, successive UK central and local governments have belatedly agreed with this view and actively pursued policies that encourage greater residential density. Partially as a result of these, the UK stands today as the most densely populated large country in Europe. However, the country’s ongoing housing crisis means that the national policy of densification is set to intensify further with the recent announcement of two major changes to national and local planning policy.

Last month the prime minister announced potentially sweeping changes to how land is developed in her draft proposals for the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF). These included giving councils powers to refuse development on the grounds of insufficient density, renewed emphasis on brownfield development, further measures to promote the conversion of shops into housing and crucially, the reintroduction of minimum density targets for housing developments around transport hubs and in city centres.

These developments follow hot on the heels of last December’s draft London Plan, which, too, announced a wide-ranging set of new densification measures for the capital. As with the NPPF, greater densities are to be encouraged around city centre transport hubs, higher densities are to be promoted in the suburbs.

The political impetus behind these revisions is clear: it is simply to raise density in an attempt to increase housing supply and thereby ease the housing crisis. The Greater London Authority (GLA) seeks to double London’s housebuilding target to almost 65,000 new homes a year and central government has committed to increasing housebuilding target by almost 50% to 300,000 new homes a year in order to create 1 million new homes by 2020.

The changes are perhaps most radical in London, where the density matrix (see Density: defining terms, above) has effectively been scrapped. It will be replaced by a more ambiguous requirement to ensure that high densities are supported by a management plan on case-by-case basis. The plans have received predictably mixed reactions.

Density: defining terms

Superdensity Term coined by landmark Superdensity reports of 2007 and 2015 by HTA, PRP, Pollard Thomas Edwards and Levitt Bernstein. It defines superdensity as any development with more than 350 dwellings per hectare (dph)

Nation Planning Policy Framework Before 2012, Planning Policy Guidance 3 (PPG 3) set a minimum density of 30dph for residential development. The introduction of NPPF in 2012 removed this requirement and gave local planning authorities the freedom to set their own density thresholds in line with local circumstances. Now, minimum densities may be reintroduced.

London Density Matrix First introduced in its current form in 2004, this is a formula that uses the distance of a residential development from public transport hubs to dictate its densities varying from 150 to 1,100 habitable rooms per hectare (35-405dph).

Reception

Many in the industry have applauded the new revisions to density targets, with Russell Curtis, RCKa Architects director and mayor’s design advocate, welcoming the London Plan’s density changes as “good news” and Ian Anderson, partner in Cushman & Wakefield’s planning and development team, hailing the draft NPPF as a “big opportunity for planning reform to increase housing density […] and to make it as easy as possible for brownfield sites in town and city centres to be converted to residential.”

But others were more cautious, with Julia Park, head of housing research at Levitt Bernstein warning that “a fine balance must be struck between the overwhelming demand for numbers and the need to protect quality and create a lasting legacy.”

Duncan Bowie, former lead housing planner at the GLA and one of the key instigators of the London density matrix, goes further, accusing the new draft London Plan of “ignoring the relationship between density and type of housing output” and stating that “the focus on densification represents a failure to consider the benefits and dis-benefits of alternative development options”. He also predicts that the unilateral pursuit of higher densities and the abandonment of the London density matrix will do all of the following: lower affordability, reduce sunlight levels, restrict privacy and – since it reduces amenity space – create inadequate housing for families.

To find out how high-density housing might work best under the proposed NPPF and London Plan density targets, we explore two new London schemes that have already been built to around “superdensity” levels, and might offer clues as to what residential development and housing quality might look like were proposed densification measures to be introduced.

Population density of some UK and global cities

inhabitants per square mile

Manila: 184,570

Mumbai: 73,837

Paris: 55,673

Barcelona: 40,000

New York: 27,000

Tokyo: 16,120

London: 15,400

Portsmouth: 13,365

Manchester: 11,439

Birmingham: 10,391

Los Angeles: 7,544

Cardiff: 6,400

Glasgow: 3,521

Abell & Cleland House

Westminster, London (2018)

Architect: DSDHA

Developer: Berkeley Homes

Units: 275

Affordable: 25%

Storeys: 13

Density: 1,033 habitable rooms per hectare / 319 dwellings per hectare

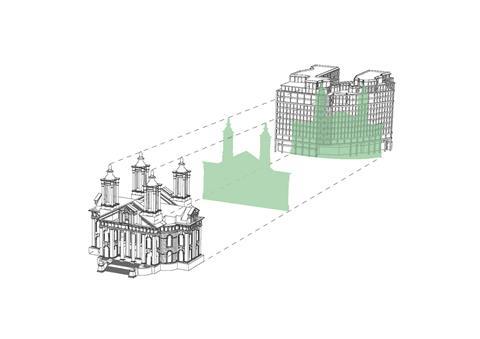

Achieving high density is often tricky, as it’s not every location that has the social or transport infrastructure to support mass housing. But doing it in a historic area only yards from the Westminster Unesco World Heritage Site and directly opposite the high-security MI5 headquarters – one of the most sensitive sites in the country – makes the attempt even more challenging.

But according to Deborah Saunt, co-founder of architect DSDHA, the process of achieving high density was actually helped rather than hindered by the historic context, since the densities often sought today were routinely achieved in the 19th and early 20th centuries. “Luckily it’s in an area of big buildings. Slums and rookeries here demolished in the 1920s and 30s and replaced with large residential and office buildings such as Dolphin Square and the Millbank Estate. These already achieved high densities and set an important precedent that we were able to respond to,” says Saunt.

That response comes in the form of two handsome stone-fronted blocks that face each other across opposite sides of John Islip Street and are clustered around gardens. The biggest, Abell, contains 141 private units while Cleland houses 118 units, around two-thirds of which are affordable. But while such a substantial level of affordable housing in one of the country’s most prestigious neighbourhoods is impressive, it is the scheme’s exceptional density score of 319 dwellings per hectare that is significant.

Incredibly, DSDHA has calculated that in terms of site usage, the development is 2.1 times more dense than Erno Goldfinger’s seminal Trellick Tower, built in north Kensington in 1972. Furthermore, were Trellick Tower to achieve the same level of density as Abell and Cleland, it would need to be 66 storeys high, well over twice its current height.

So how did the scheme do it? For Saunt, there was a key driver: courtyards. “The idea of using the courtyard model along with the gardens were the missing elements that enabled us to balance density with beauty and delight. Modernism tended to prohibit courtyards but the residential courtyard model is highly effective in providing a large number of units while still enclosing shared space, providing double-aspect flats and avoiding oppressive perimeter walls, all the elements that modernist slab housing usually failed to achieve. But crucially, it also enables a high-density scheme to have a positive impact in terms of public realm and architectural quality.”

Saunt also points out that the extruded exoskeleton that encases the buildings allows insertion of terraces and balconies between the two skins of the facade, extending the pattern of private and shared amenity vertically as well as horizontally. Amenity space such as gardens and communal areas are often thought to be one of the elements sacrificed to deliver high density, which is often alleged to make it inappropriate for family housing. As well as the courtyards, Saunt also identifies “wide corridors and generous lobbies” as other design features that “balance density and beauty.”

The Trellick comparison also inevitably allows Saunt to compare the relative merits of mid and high-rise housing for providing high density and she has no doubt which model wins. “It’s a myth that high-rise automatically means high density. Towers come with a host of cost and environmental problems and unless you’re building the super-tall towers we’re now seeing in New York, they’re hopelessly inefficient.

“Mid-rise however can achieve higher densities while still providing an opportunity to connect with the street and ensure that gardens rather than facades have the biggest public realm impact. Unlike towers, mid-rise residential development can become part of a neighbourhood.”

In light of her work on Abell and Cleland, what then does Saunt think of the recent proposals to deliver higher densities as laid out in the NPPF and new London Plan? “More density is welcome, we shouldn’t see the centre of the city as alien in residential terms. But it has to be delivered with high-quality design at its core. There need to be meaningful outdoor spaces, a total engagement with context and a renewed respect for local precedent. We need to go back to design basics to ensure that density is delivered within a tailored urban response.”

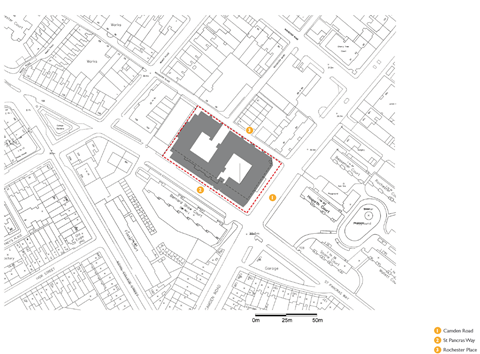

Camden Courtyards

Camden, London (2018)

Architect: Sheppard Robson

Developer: Barratt London

Units: 164

Affordable: 50%

Storeys: 7

Density: 1142 habitable rooms per hectare / 410 dwellings per hectare

With its ashen brickwork, strong vertical proportions and muscular attic storeys, Camden Courtyards, lying between Camden Town and Kentish Town, is a block of flats carved straight from the London vernacular handbook. But its modest appearance belies the fact that this housing development has a radical approach to design that enables it to achieve a density of 1,142 habitable rooms per hectare, one of the highest densities attained on any recent mid-rise London housing scheme.

It does so by being closely based on European precedents. “I’ve lived in both Paris and Berlin and in both those cities you offer a very high-density context of compact and close-knit accommodation that isn’t oppressive but on the contrary is extremely civilised and convivial. They’re also often based on a key residential model that we built this scheme around: courtyards.”

So it would seem that here as well as at Abell and Cleland, courtyards are the magic ingredient that unlocks high density. At Camden Courtyards the building assumes an “S” or double-doughnut plan that enables the building to tightly wrap around two sheltered courtyards. According to Burr, this immediately solved a number of layout problems and offered a slew of density-related advantages.

“It ensured that despite the site being surrounded by two busy main roads, we were still able to maximise accommodation by arranging the building around quieter, sheltered courtyards. We were also able to achieve a high number of dual-aspect flats and the double-courtyards meant we had a profusion of corners which in layout terms generated some flats with multiple aspects and a quirky, interesting character. Crucially, by also placing cores within these corners, we were also able to group no more than eight flats around a single core and ensure that flats were served by relatively short corridors.”

The level of intimacy and individuality these measures achieve are important factors in diluting the institutional impersonality high-density schemes can sometimes evoke. Also, despite being attractively landscaped, Burr is careful to point out that as per the European model, the courtyards are prioritised for circulation rather than communal amenity use. Private and shared amenity space comes in the form of the inset balconies and communal terraces.

Despite the significant role the courtyards play in delivering high density, Burr also reveals that there were three other important aspects that enabled the site to be used so efficiently. “First, the site is located in a high activity area with lots of public transport, retail and leisure amenities already provided. Secondly a local authority requirement was that there was no on-site parking, thereby unlocking the entire lower ground floor for flats rather than a car park. And finally the site dimensions are optimal for housing”.

The site is approximately 46m wide, which is the perfect dimension for two 14m blocks with an 18m courtyard in the middle. Also, 14m deep is an optimal width for a residential block to provide dual aspect units and 18m provided an ideal courtyard dimension for overlooking distances. This also determined the height of the seven-storey blocks in terms of admitting sufficient daylight into the courtyards and flats, some of which achieve daylight performance indicators of up to 87%.

Despite Camden Courtyards’ impressive performance in density terms, Burr is less willing than Saunt to dismiss high-rise outright in favour of mid-rise, claiming that “if high-rise is done well, it need not be aggressive or out of scale and can work well with existing townscape.” The challenge, he maintains, is “high density not high-rise” and convincing people that high-density can still deliver “a network of green and amenity spaces, family accommodation and affordable housing.”

Accordingly he supports the new density measures drafted by the GLA and central government and offers Camden Courtyard as a “neat diagram that sets a benchmark” for how densification can be responsibly achieved. “Achieving higher density is about holistic design, not numbers. Good design and a variety of responses will be central to balancing housing and townscape needs and crafting an appropriate response to context and setting that isn’t brutal or overbearing. If this can be done then there’s a huge potential for good architecture to unlock the housing potential of sites across the country.”

So, is density our destiny?

The NPPF and the London Plan seem to signal a deliberate push towards building UK housing at higher density than has typically been seen in recent years. But does this mean a proliferation of high-rise blocks?

It is significant that both schemes considered here attribute their high densities to the utilisation of courtyards, and ironic that this traditional low-rise building format could unlock the higher densities that were more commonplace in British cities up until the second half of the twentieth century. Therefore there seems to be a strong case for the claim that the high densities being pursued by the new NPPF and draft London Plan can be beneficial, as long as high quality design is used to deliver them.

But there is another important consideration that both case studies give more weight to than the current legislative revisions: context. High density cannot be autonomously imposed and must be appropriate to its surroundings. Therefore the NPPF and draft London Plan need to work harder to strike a responsible balance between numbers and the quality of the wider neighbourhood.

No comments yet