Olympique Lyonnais’ new £340m home, designed by Populous, will host Euro 2016 matches this summer. But is it more typical of English stadium design than its continental counterparts?

While English national football struggles as a credible export commodity, English stadiums fare considerably better. European stadiums tend to be rather more consensual affairs than their English equivalents, with stadium sharing between teams and athletics tracks – both largely anathema in top-flight English football – being relatively common. In many ways several European football stadiums are the conceptual equivalents of the horseshoe parliamentary chambers favoured across the European continent that are, in theory at least, said to breed courtesy, consensus and collaboration.

English stadium design on the other hand, rather like our gladiatorially confrontational House of Commons, tends to take a somewhat more aggressive approach. English stadiums are famed across Europe for the intensity and implied oppression of their design, with steeper stands, encircling roofs and the lack of athletics tracks said to foster a more energised connection between spectator and pitch.

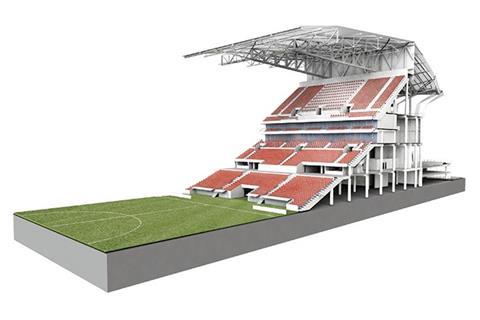

The latest European stadium partially inspired by these ideas is the new home of football club Olympique Lyonnais in Lyon. The £340m Grand Stade de Lyon, nicknamed the Stade des Lumières, in eastern France opened last month and replaced Lyon’s former 40,000 capacity Stade Gerland, which was built in 1926. The new 59,500-seater stadium was designed by stadium veteran Populous, architect of several iconic football grounds across the world, including Arsenal’s Emirates stadium in London.

Commercial imperatives

In fact, the Emirates stadium, which saw the creation of one of European club football’s most architecturally renowned and economically successful home grounds, proved another big inspiration for Lyon. Whereas in England the vast majority of football clubs own their grounds privately, the opposite is the case in France and, incredibly, Lyon is one of only two privately owned major football stadiums in the country and is the only club in France’s top division whose stadium is not owned by the local municipality.

There was therefore a tremendous imperative for the stadium to realise the kind of commercial revenues that have been so successfully accrued at Arsenal. The stadium design attempts to facilitate this financial ambition in three ways. First, the stadium itself is only the first phase in a wider masterplan that will eventually see it surrounded by homes, hotels, offices and multiple leisure and entertainment amenities. To facilitate this future development the stadium is encircled by an expansive raised podium which is treated as a public space designed to mediate between the stadium and planned future developments around its perimeter.

Secondly, the stadium offers a wide range of conferencing, hospitality, dining and corporate entertainment facilities on a scale not normally seen in French club football grounds. And, thirdly, the stadium has been designed as a flexible multi-purpose venue that can accommodate a wide variety of different sports and also host a diverse range of non-sports activities, such as music concerts, public performances and community events.

Accordingly, the Stade des Luimières will also host the rugby European Champions Cup final in May, as well as group and knock-out stage matches from the Euro 2016 European Football Championships, to be held in France this summer. Flexibility is ensured for these and all events by the ability to reduce its seating capacity down

Design influences

The design concept for the stadium is jointly influenced by local context and English stadium traditions. The structure sits in what can be loosely seen as the equivalent of Lyon’s green belt. This imposed a number of landscaping constraints, including the requirement to somehow accommodate parking for 4,500 cars around the stadium on soft rather than hard landscaping. The result is a 90,000m² grass car park, which is the largest turf park in Europe.

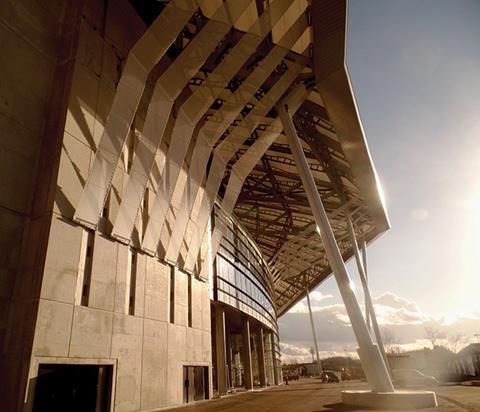

Local natural landscape, as well as historic precedents, also heavily informed the stadium structure. The stadium is essentially a concrete seating bowl enclosed within curving external concrete walls and surmounted by a vast, lightweight roof. The external walls beneath the roof are designed to overawe and intimidate opponents, sporadically punctuated with vertical narrow openings intended to mimic a medieval fortress built to defend the home team.

The roof, however, plays a far more conciliatory and conceptually significant role. In many ways the roof is the culmination of all the various conceptual drivers the stadium design is attempting to embrace. It provides the sense of continuous, full enclosure essential to replicating the intense cauldron atmosphere the design team has identified as a facet of English stadiums.

It also helps address the green belt location by forming an architectural representation of the canopy cover provided by trees in surrounding local forests. The roof is supported by a series of inclined steel columns designed to mimic the lean and sway of tree trunks. And the enwrapping roof structure folds and undulates to ape the natural shelter offered by branches and leaves.

In meeting these twin ambitions, the roof itself becomes a formidable and impressive structural entity in its own right. Measuring 53,700m² it is one of the largest stadium roofs in the world. Its steel trusses support three linked roofing systems. The inner roof over the stands is finished in polycarbonate sheeting. The middle section over the stadium structure is clad in an insulated corrugated steel membrane. And the outer roof over the podium comprises an innovative new lightweight flexible composite fabric known as Precontraint TX30.

Developed by French industrial manufacturer Serge Ferrari, this fabric has its origins in the silk weaving that French Huguenots (a protestant Christian group) have been renowned for for centuries and brought to the East End of London in the 17th century. Today it is polyester yarn that forms the basis of the material which is spun, overlaid and then coated with PVC resins to provide a strong, durable but lightweight architectural material.

Precontraint TX30 is so named because it is manufactured by means of a crosslinked process normally used on rigid materials and offers a 30-year guarantee. In total 33,000m² of the fabric is used on the stadium and its section of the roof is divided into 144 panels of varying widths but all 37m in length.

The use of the fabric was essential to provide the canopy expression that was central to the “tree shelter” architectural concept. However, it presented a key construction challenge. While France enforces no specific building regulations with regard to the construction of flexible roofs, common practice dictates that they adopt some kind of curvature in order to withstand bad weather and minimise snow loading.

However, prior to the fabric being selected, the architectural design specified an inclined but flat surface to provide a sinuous canopy appearance, minimise complexity and maximise stability. The compromise as built features an undulating series of faceted fabric panels that still satisfy the stringent tension control requirements demanded by the flexible fabric but also provide the dimensional stability required to enable the roof effectively to perform its structural role.

Stadiums once had a reputation for being works of engineering rather than architecture. The increasing utilisation of design innovation and ambition on stadiums worldwide has reversed this trend and encouraged stadiums to be viewed as works of architecture in their own right. The Stade de Lyon certainly adds to this process and in its hybrid assimilation of both French and English traditions proves that stadiums can have cultural potency too.

No comments yet