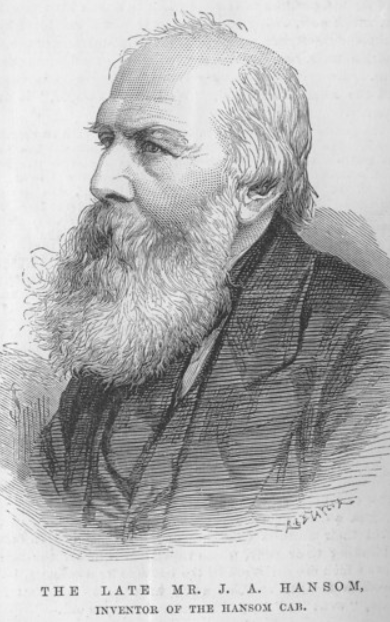

To celebrate Building’s 180th anniversary, Tom Lowe talks to historian Penelope Harris ahead of the publication of her biography of the magazine’s founder

It was a chance encounter with a street sign that inspired the new biography of Building magazine founder Joseph Aloysius Hansom. Its author, historian Penelope Harris, was driving into the Leicestershire market town of Hinckley to take up a new job when the sign caught her eye.

Hinckley has a long history. It was founded in Anglo-Saxon times and was mentioned in the 11th-century Domesday Book. It was also close to the site of the Battle of Bosworth, which ended the Wars of the Roses, and a key battleground of the 17th-century English Civil War.

But the sign which marked the entrance to the town proclaimed: “Hinckley: Home of the Hansom Cab”. The “hansom” for those who don’t know, is a two-wheeled carriage invented by Joseph Hansom in 1834.

Light enough to be drawn by a single horse and with a low centre of gravity to prevent it toppling over while turning tight corners, it was a Victorian phenomenon. Some 7,500 of the cabs plied the streets of London during the 19th and early 20th centuries, and they were exported in large numbers overseas to cities including New York, Paris, Berlin and St Petersburg.

It was an early triumph for its namesake, whose reputation had been boosted a few years earlier with his work designing Birmingham’s neoclassical town hall, now a grade I-listed and still much loved landmark of the city centre. He would go on to have a glittering, if chaotic, career in architecture which saw him become one of the 19th century’s pre-eminent designers of Catholic churches. It was in Hinckley where Hansom founded Building magazine, originally known as The Builder, in 1843, making this its 180th anniversary year.

Harris is from a family related to the Hansoms, but she had no idea that she had a connection to the town before arriving. It was the latest in a string of coincidences that seemed to be urging her to write the book which she is now close to completing, and which is due to be published next year.

When she was growing up she was made aware of the hansom cab and Arundel Cathedral, another of Hansom’s grade I-listed designs, but the architect was not much talked about. After leaving school, she lived in a flat in South Kensington, close to where Hansom lived for several years. Much later she had a job in Kent at a firm which held its AGMs in West Kensington, coincidentally next door to a house previously owned by one of Hansom’s close relatives.

After seeing the sign in Hinckley, Harris joined the local history group and was put in touch with the widow of Dr Denis Evinson, whose masters degree was based on Hansom’s life. His thesis “intrigued me”, Harris says. “How did Hansom work across the whole country, often simultaneously in locations very far apart?”

Her interest led her to get in contact with someone who was working on a major restoration of Birmingham Town Hall. He showed her around the building, which at the time was completely enshrouded in scaffolding.

It was after this visit that she started her research into Hansom in earnest. This quickly turned out to be a more daunting task than she expected. Hansom lived a highly mobile existence, hopping from town to town as he managed multiple projects in different parts of Britain at the same time.

“When I first set out to write Hansom’s biography, I naively thought I could begin in York, his birthplace, and follow through chronologically,” Harris says. “How very wrong - there was nothing logical in his life, which made the assemblage of a structure extremely challenging.”

But she soon started to accumulate a large amount of background information as she embarked on a zig-zag tour of the country, tracing Hansom’s steps from project to project. “Almost with a sense of destiny, it became something I had to do, becoming more and more personal, especially over the last few years,” she says.

In the Talbot Library in Preston she unearthed an original copy of Hansom’s entry into the 1855 Paris Exhibition. In Liverpool, she met an archivist who showed her letters regarding Hansom’s Training School for Catholic Schoolmistresses.

She also found extensive letters regarding the design of a church in Selby, North Yorkshire. She made the discoveries just in time; the Preston Library is now closed, and the Liverpool archives have been transferred to Belgium.

Numerous priests and nuns were also very welcoming and helpful with good records, sharing primary documents not to be found elsewhere, Harris says.

Other sources have included Building itself (previously called The Builder), archive copies of which are held in several libraries. From local newspapers she found details of opening ceremonies, lists of people involved in various schemes, including financiers and benefactors.

From archives in Birmingham she found a collection of letters between Hansom and stained glass designer John Hardman, who was married to one of Hansom’s daughters, while another daughter was married to Hardman’s chief draughtsman. The letters not only revealed technical details, but occasional glimpses into Hansom’s family life.

>> Also read: The many lives of Joseph Aloysius Hansom

Harris describes Hansom as a “true Victorian”, a man of almost manic energy, both in his work and his spiritual life. A devout Catholic, he was also active in early socialist politics. He had a Dickensian approach to social conditions, supporting the poor and encouraging education at all levels, Harris says.

As the Great Reform Act was making its way through Parliament in the 1830s, Hansom was encouraging his own workers to join unions. He took part in rallies of up to 200,000 people with social reformers Robert Owen and Daniel O’Connell. He even designed a guild hall for the builders union, placing a box beneath the foundations that declared a “confident hope of a new era in the condition of the whole of the working classes of the world”.

Yet his own financial position in those early years was always on the verge of, and sometimes was, collapsing. He won the commission to design Birmingham Town Hall through what would now be called suicide bidding, estimating a cost of £16,600, some £6,000 lower than the next cheapest entry.

His design, based on the Greek temple of Castor and Pollux in Rome, beat a shortlist including some of Britain’s greatest architects at the time – including future Houses of Parliament designer Charles Barry and Bank of England architect John Soane – to win the job.

But it came at a great personal cost. It appealed to the Birmingham street commissioners, the equivalent of a town council, but they did not trust his lack of experience or the financial shortcomings of his builder. To convince them, he agreed to act as the financial guarantor for the scheme.

This was highly unusual and unethical, but Hansom was “so keen to ‘have it’ as he proclaimed, that he threw caution to the wind and accepted”, Harris says. At this time he was working in three places simultaneously – Liverpool, Anglesey and Birmingham – but the commissioners denied him any travel expenses.

He battled on, “stretching his ingenuity to its limits”, working all hours and even purchasing a brickyard and resorting to loans, including from his partner’s father. He then suffered a tragedy when a hook on the pulley-block lifting the roof timbers snapped, throwing three workmen flying and falling the full height of 70ft from the scaffolding to the ground, killing two of them.

The final straw was a delayed shipment of marble from Wales, forcing Hansom to declare bankruptcy. The commissioners took the town hall project from him and gave it to Liverpudlian architect John Foster. Hansom was so shocked that he published a “Statement of Facts”, explaining how unfairly he felt he had been treated, and bemoaning that “his household goods were gone – my children and my wife had no home to call their own, no bed to lie on, no bread for his parents for he had none to give’ ”.

Though it turned out to be the making of his career, it was not the last of Hansom’s projects which suffered misfortune. During the construction of a cathedral he designed in Plymouth, defects were uncovered in a wall and the roof caved in, while two columns were found to be defective and replaced with granite.

Hansom was working in Boulogne-sur-Mer at the time and his brother, Charles, rushed to the scene. The incident was so great that the city surveyor was called upon to surround the building with a police cordon.

Hansom also became engaged in a “bizarre” partnership with Edward Pugin, the son of Augustus Pugin, designer of Big Ben and the interior of the Houses of Parliament. The pair planned to design and build a church in Edinburgh for the local bishop and a large school of ecclesiastical art.

Hansom arranged for 500 workers to be relocated from Preston and leased a large building nearby which was to be the initial site for the school. Disputes quickly arose between him, Pugin and the bishop, who eventually withdrew all funding. The partnership between the two architects barely lasted a year and culminated in Hansom taking Pugin to court, resulting in much mudslinging. The two were “incompatible”, Harris says.

Even Hansom’s invention of his famous cab turned sour. In order to focus more on his architectural work, he sold the patent to a cohort of directors who promised him £10,000, but eventually handed over just £300.

His editorship of The Builder was also short lived. The weekly journal he founded in 1843 was inspired by his political involvement and Robert Owen’s philosophies from time spent in Birmingham, but it suffered from lack of capital. Just a year after it was launched, and with its readership floundering, Hansom sold the publication to his printers JL Cox & Sons.

Against all the odds, The Builder survived, changing its name to Building in 1966, and the magazine Hansom founded is still going strong 180 years later. It is now among the oldest business-to-business magazines still printed anywhere in the world.

Hansom eventually achieved a more stable financial position, becoming comfortably well off later in life, although Harris says he was never really wealthy. After a career of more than five decades, he retired in December 1879 at the age of 76, dying less than three years later.

Historian Joseph Gillow said after Hansom’s death, remarking on the famous cab: “It is given to few to see their names spelt with a small initial, a distinction which assuredly marks extreme celebrity.”

From the Building archives

To celebrate Building’s 180th anniversary, we have been trawling through our achives to find some of our most interesting journalism. See below

>> Nelson’s Column runs out of money, 1843-44

>> The clearance of London’s worst slum, 1843-46

>> The construction of the Palace of Westminster, 1847

>> Benjamin Disraeli’s proposal to hang architects, 1847

>> The Crystal Palace’s leaking roof, 1851

>> Cleaning up the Great Stink, 1858

>> Setbacks on the world’s first underground railway, 1860

>> The opening of Clifton Suspension Bridge, 1864

>> Replacing Old Smithfield Market, 1864-68

>> Alternative designs for Manchester Town Hall, 1868

>> The construction of the Forth Bridge, 1873-90

>> The demolition of Northumberland House, 1874

>> Dodging falling bricks at the Natural History Museum construction site, 1876

>> An alternative proposal for Tower Bridge, 1878

>> The Tay Bridge disaster, 1879

>> Building in Bombay, 1879 - 1892

>> Cologne Cathedral’s topping out ceremony, 1880

>> Britain’s dim view of the Eiffel Tower, 1886-89

>> First proposals for the Glasgow Subway, 1887

>> The construction of Westminster Cathedral, 1895 - 1902

>> Westminster’s unbuilt gothic skyscraper 1904

>> The great San Francsico earthquake, 1906

>> The First World War breaks out, 1914

>> The Great War drags on, 1915 - 1916

No comments yet