News item on the death of engineer Sir Thomas Bouch, who designed the bridge which collapsed in a storm killing 75 people

The collapse of the Tay Bridge was one of the worst engineering disasters of the 19th century. At more than 3km long, the bridge was the largest ever built when it opened with great fanfare in May 1878. Queen Victoria herself had travelled over it and its designer, the engineer Thomas Bouch, had been knighted.

But, on a stormy night in December 1879, disaster struck. Steel cross-bracings buckled under high winds, tearing down the entire middle section of the bridge. Around 75 people who were travelling across the bridge in a passenger train died when the carriages crashed into the waters of the River Tay.

Bouch, who we mentioned in last week’s archive piece about the Forth Bridge, was at that time considered among Britain’s greatest engineers and at the peak of his career. His reputation was utterly ruined by the collapse of the Tay Bridge, for which he was held responsible.

He had been appointed to design the Forth Bridge and construction on his scheme had begun at the time of the disaster. He was swiftly removed from the project and a new design was drawn up. A public inquiry in 1880 found the Tay Bridge had collapsed due to a series of design flaws, including piers which were too narrow, and decisions made by Bouch which had not made allowance for high wind loads.

Bouch died later that year, a “stricken man”. The news item below reports on the “sorrowful ending of so successful a career” .

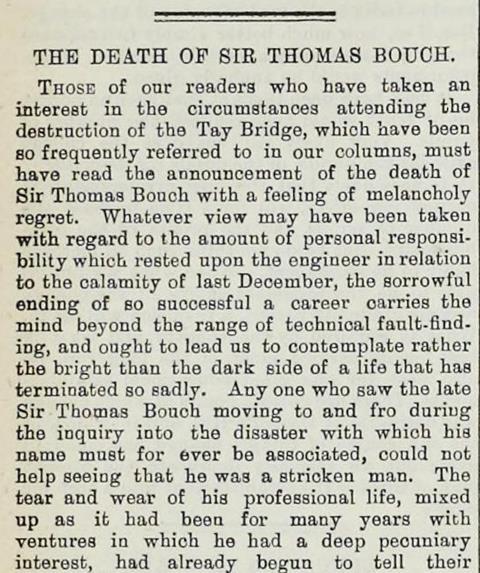

News item in The Builder, 6 November 1880

THE DEATH OF SIR THOMAS BOUCH

Those of our readers who have taken an interest in the circumstances attending the destruction of the Tay Bridge, which have been so frequently referred to in our columns, must have read the announcement of the death of Sir Thomas Bouch with a feeling of melancholy regret. Whatever view may have been taken with regard to the amount of personal responsibility which rested upon the engineer in relation to the calamity of last December, the sorrowful ending of so successful a career carries the mind beyond the range of technical fault-finding, and ought to lead us to contemplate rather the bright than the dark side of a life that has terminated so sadly.

Any one who saw the late Sir Thomas Bouch moving to and fro during the inquiry into the disaster with which his name must forever be associated, could not help seeing that he was a stricken man. The tear and wear of his professional life, mixed up as it had been for many years with ventures in which he had a deep pecuniary interest, had already begun to tell their tale.

When, in addition to all this, he suddenly found himself thrust out of the position of trust and responsibility which his abilities had rendered apparently secure, and placed in an attitude of defence towards the work of his own intellect, and the anxious labour of years, the strain that was thrown on his constitution could be read by the passer-by.

The circumstances, in the mere aspect of their human interest and as a commentary on the vanity of human affairs, appear to us to afford the materials for a tragedy, the motive of which is peculiar to the times we live in. In the climax, when the fates have come with the shears, the end, instead of being a culmination of the sorrow, is rather of the nature of a kindly remedy for evils that could not longer be borne.

It is very questionable if any opportunities that might have been afforded by the prolongation of life, even beyond the common span, would have so altered the aspect of what has passed as to have removed the causes of mental anxiety and suffering. We hope that, now he has gone, the lesson he has left to the living may never be taught at the expense of a kindly regard for the dead.

The curtain has fallen on a human tragedy, which we have already spoken of as having a motive peculiar to the times we live in. It is true that in its external aspect there is not much to strike the mind as different from the exigencies of an ambitious career in all ages. The successful general who, after having conquered his enemies, has himself been conquered, is a familiar subject for the dramatist.

With him each action of his life has to be judged from the individual circumstances surrounding it. If his enemies were fighting for their rights, success could never justify the object of his labours. But in this 19th-century tragedy we find a general in the army of labour, fighting in a noble cause, who has fallen a victim to the inexorable watchfulness of natural laws that are ever ready to revenge themselves upon mistakes. The foes with whom he fought were never encountered in support of an evil cause.

Let us not, then, think of Sir Thomas Bouch as one who destroyed the Tay Bridge, as might have been done by the leader of an invading army. He did his best, in circumstances surrounded by trial and difficulty, to make it secure. In his battle with the elements, it was at least his sincere wish to succeed in the interests of progress and civilisation.

Even those who were ready to quote the sad death of the sufferers from the accident as a ground for indictment are silenced by the mournful event that has followed. Sir Thomas has died of a broken heart, and gone to join the multitude of the rank and file of the army of labourers whose lives, in the great vortex of modern civilisation, have met with an untimely end. In spite of the sad termination to his career, we can still look back on his previous work, and deplore the loss of a great builder.

Requiescat is a sentiment that all men, even those who felt most keenly and spoke most loudly about his responsibilities, will now be ready to express. Rest from such afflictions appears the most merciful interpretation of death when hope has ceased to secure a hearing.

More from the archives:

>> The clearance of London’s worst slum, 1843-46

>> The construction of the Palace of Westminster, 1847

>> Benjamin Disraeli’s proposal to hang architects, 1847

>> The Crystal Palace’s leaking roof, 1851

>> Setbacks on the world’s first underground railway, 1860

>> The opening of Clifton Suspension Bridge, 1864

>> Alternative designs for Manchester Town Hall, 1868

>> The construction of the Forth Bridge, 1873 - 1890

>> The demolition of Northumberland House, 1874

>> Dodging falling bricks at the Natural History Museum construction site, 1876

>> First proposals for the Glasgow Subway, 1887

No comments yet