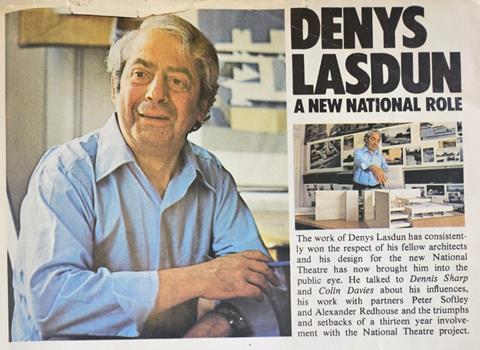

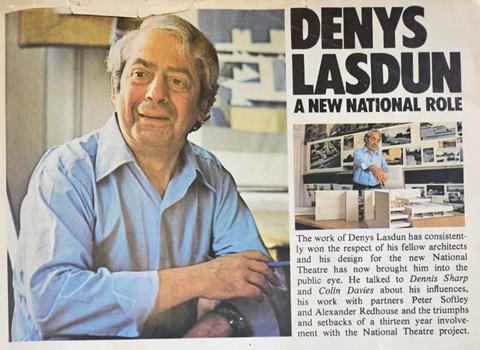

Building interviews legendary modernist architect Denys Lasdun following the opening of his masterpiece on London’s South Bank

Denys Lasdun’s National Theatre is widely considered one of Britain’s greatest modernist buildings. Completed in 1976 and now grade II*-listed, it was a project first conceived in the 19th century but repeatedly delayed, not least during its troubled construction.

In an interview with Building, Lasdun talks about his design approach for the theatre and the challenge of having to deal with constant government budget cuts. He also comments on his influences, his time as an engineer in the Second World War and why he found Le Corbusier’s utopian ideas “terrifying”.

Interview, 17 September 1976

DENYS LASDUN

A NEW NATIONAL ROLE

The work of Denys Lasdun has consistently won the respect of his fellow architects and his design for the new National Theatre has now brought him into the public eye. He talked to Dennis Sharp and Colin Davies about his influences, his work with partners Peter Softley and Alexander Redhouse and the triumphs and setbacks of a thirteen year involvement with the National Theatre project.

After leaving Rugby School Denys Lasdun went straight to the Architectural Association, London in 1931. His family had no direct connection with architecture.

His father, who died when Lasdun was only six, had been concerned with engineering and was a cousin of the famous French designer Leon Bakst who worked with Diaghilev. His mother was a pianist but the main connection his family had with the art world was through his paternal grandfather who was one of the founders of the Australian Impressionist Group in Melbourne.

His own interest in architecture was stimulated by a fellow student at Rugby, Bill Henderson, who at the time was going off to Reilly’s famous school at Liverpool.

Lasdun entered the AA First Year when it was going through a Neo-Swedish mood. A teacher who made a big impression on him was S Rowland Pierce, himself a classicist architect, who is probably best remembered today as a fine draughtsman and one-time co-editor of the book Planning.

Apart from Pierce, Lasdun was also influenced by EA Rowse who took over from Howard Robertson at the AA. “Rowse made it clear that architecture was a social art, to do with society’s values, which made me pick a thesis on housing”.

This sort of fresh thinking led to Lasdun’s early concern with town planning matters and cities. He still finds difficulty in understanding the incompatibility that exists today between the disciplines of planning and architecture.

Blurred boundaries

Referring to the current situation, he sees planning and architecture as interdependent: “I find the boundaries very blurred and I would be, I think, a lot happier if we accepted that the boundaries were blurred and not that there’s one very hard-and-fast division that calls itself town planning and another called, to use the overworked word, environment. It’s both buildings and collections of buildings and places; there is no rigid boundary.”

Lasdun speaks of the great impatience his generation at the AA felt with a five-year seclud- ed life. “We wanted to be far more involved, as indeed students always do.” But things were not always serious and he remembers with a smile that “the cinema on the corner (of Tottenham Court Road) used to run a programme which started at 2 o’clock in the afternoon and didn’t end till about 6, so it took care of the afternoon… it was a place we used to go to often”.

At the time Lasdun was an AA student, there were forces at work in European architecture which were eventually to have an irreversible effect on British design. Among these were new ideas on the use of reinforced concrete, on plainness in design, on a geometrical architecture and on “modernism” as an ideology. In 1927 the publisher John Rodker produced an English translation of Le Corbusier’s tract Vers une Architecture (translated by Etchells as Towards a new Architecture).

Lasdun recalls the impact this book had on him in the early 1930s: “I was absolutely hooked on Vers une Architecture, it was like a duck taking to water. I read it from cover to cover more than once and I went to Paris almost immediately… there was no question at all that this was what architecture was about and the way I was going… I found Le Corbusier’s Pavillion Suisse in Paris stunning.”

An AA project designed by Lasdun in the Corb manner (a hostel in Regent’s Park), received a “first mention” and in 1935 was his first published scheme. While it can clearly be seen that Corb’s ideas have been behind the development of Lasdun’s work, over many years this pronounced influence has been essentially architectural, and he is less inclined to accept Corb’s views on planning: “I was never attracted by, or accepted, any of the urbanist utopian theories - they struck me as terrifying.”

In 1934 Lasdun left the AA School to work for Wells Coates, another completely convinced Corbusian, and the founder of the English group of modern architects MARS. Lasdun worked on Coates’s Palace Gate flats. He also began to see the hazards and potentialities of reinforced concrete. However Coates was short of work and when Lasdun received a commission to design a house in Paddington for a friend, Bob Conway, he went out on his own.

First solo piece

The Paddington house, Lasdun recalls, “was my first solo piece of modern architecture”. It was Corbusian in essence with an added feeling for more friendly materials - Dutch tiles which had probably been seen by Lasdun in Tecton’s work High Point 2 at Highgate.

Lasdun next moved to Lubetkin’s Tecton group with whose later work he is closely associated. He joined at the time the Tecton Partnership was completing work on the Finsbury Health Centre. After that came reinforced concrete air-raid shelter work and eventually the outbreak of war.

Lasdun enlisted: “I went into the Engineers and was in charge of heavy earth moving equipment. Our job was to make advance airfields and we flattened everything in sight in order to make these rapid airfields. I made one of the first airfields of the war at Arremand, Normandy. I off-loaded all the equipment in 12-feet of water.”

This little known aspect of Lasdun’s career is important from a number of points of view, not the least of which is the comment he made in our interview that “I found those earth-moving machines extraordinarily exciting and I liked making hills, banks and ditches”. He commented: “It is earthbound architecture that I am interested in”, a reference back to his war years, but an idea reflected in the layout of the University of East Anglia.

After the war Lasdun returned to London and to the firm Tecton. It was a questioning period for Lasdun and his colleagues; indeed, with the return to normality controversy was in the air. Tecton, and Lubetkin in particular, was attacked as formalist but Lasdun felt that he wanted to go in another direction.

“I wasn’t sure which direction, but there was a definite change in my outlook and attitude although it was not to emerge for a while yet. I was doing the Paddington scheme with Redhouse and Drake presumably at the moment when Tecton were under the attack for formalism.” Tecton was dissolved in 1948 and the Tecton Paddington housing scheme was completed by Drake and Lasdun.

At the time of its completion Lasdun had a telephone call from Maxwell Fry saying that he was off to Chandigarh with Le Corbusier and asking him to look after his office. Drake joined him as a caretaker for Fry and Drew’s practice; they did not lose their own identity as designers in this involvement. It was at this time that they were introduced to working in the Tropics.

But a more exciting job was underway at Paddington. His Hallfield Primary School marked the beginning of an important new phase in his career in 1951, as well as a significant shift in architectural ideas in the year of the Festival of Britain. In the late thirties Lasdun had, with Wells Coates, gained fourth place in the News Chronicle school competition.

Lasdun continued to be interested in school building until the opportunity arose to design the Hallfields school. This school was different from almost anything else being designed in Britain at the time. The infants classrooms were clustered around a court and the junior block was serpentine shaped, constructed in specially designed dry-assembled precast concrete parts. It looked to some critics at the time more inspired by Niemeyer than Le Corbusier; it was in fact Lasdun himself finding a creative chord.

He recalls: “Some of the feeling of putting people and buildings around a space, as distinct from anything else, so that they could all communicate with each other, even though they were only five-year-old children, was something that was going to come up again, say in East Anglia University, where the whole plan is centred not on the buildings but on the space. I think that although architecture is of course cerebral, it’s also partly instinctive.

”There is a thing called gut reaction in architecture which I am not ashamed to admit operates in this office quite a bit. It’s not necessarily a popular way of discussing architecture, but I believe it to be a true one. I’ve always been aware of a self-conscious influence between what people write and what they do, and this goes for Corbusier as much as for anybody else.”

Following the school Lasdun’s work led to the experimental residential “cluster” blocks at Bethnal Green, which in their way were two further points of reference in the changing postwar architectural scene in Britain. Influenced this time by Kevin Lynch’s article on the Grain of the City Lasdun recognised that cities do not grow in enormous pieces but that it was possible to “take an area which had had six houses on it previously and actually develop into something of substance in quite a small area… that came straight out of the infants’ cluster block (Hallfield School) of 1951 into Usk Street and then into Fairbairn Street”.

In fact it gets left behind as a solution to housing by the very different programme for the luxury flats at St James’s in 1958, followed two years later by the remarkable Royal College of Physicians in Regent’s Park. The requirements of these buildings had brought wide cultural and historical issues to bear on the design process.

Lasdun was unwilling to compromise his modern movement’s position although there were pressures to historicize. At about this time he began consciously to extend the modern movement’s theoretical basis.

Platforms or strata

The flats at 26 St James’s were reduced simply to floors which were expressed as layers, or, as Lasdun prefers to call them, strata. These strata, he is keen to point out, were not merely balconies but devices to connect one visually with the outside views. In the case of flats it was with Hyde Park and later at the National with the whole Thames panorama. He suggests that it is this notion of platforms or strata which becomes a very important feature of the work in the office: “But it isn’t just a superficial stylistic one. It has other characteristics which we haven’t touched on - the public and private domains of public buildings.

“The strata, if I may put it this way, work on the practical level - they are floors. But they also work on the formal level, that is to say they give a language. And I believe in the case of the National Theatre, which is a rather unique affair in the sense that we’re trying to make monuments out of modern architectural language, the strata can also be made to work on a symbolic level. So you can work on three fronts. Hence the preoccupation with strata.”

The strata idea, which accepts the surrounding city, is argued out in the recently published book on Lasdun’s work A Language and a Theme (RIBA Publications, 1976). This book shows the development of this central theme in Lasdun’s work. East Anglia, “a key job in the office,” according to Lasdun, brought about an orchestration of his ideas: strata, earth-moving and forming and the preoccupation with systems of precast building.

The UEA scheme, the Royal College of Physicians’ building and the National Theatre and Opera House scheme, which Lasdun says was “the best thing we have ever done” (it was scrapped in 1966), brought all the latent ideas together culminating in the maturity of approach observable at the final design for the National Theatre. The aborted scheme may well have been better but, as Lasdun is quick to point out, “evidence of what it might have been like is in the National Theatre”.

Lasdun and his partner, Peter Softley, have been occupied with the National Theatre for the past 13 years. The preliminary project was for a combined National Theatre and Opera House. The building of a national theatre for Britain has been a dream for more than a 100 years; it now exists - a fulfilment of the national ambition to have a fitting showcase for our most prestigious art form. Denys Lasdun came to the project without any previous experience of theatre design, with a completely open mind but a well established method of designing.

Clearly the distinguished building committee (it included Olivier, Brook, Hall, St Denis, Devine, Gaskell etc) knew what sort of architecture they were buying. Lasdun, for his part, was not at all sure what they wanted.

The original brief was for an adaptable theatre. Lasdun recalls: “We analysed the problems of an adaptable theatre by studying American examples and looking at what they have done by way of adaptable theatres, and realised that intellectually it was not on. In a way you can sum that one up by saying that a national theatre must cater for a tradition of Greek or Elizabethan drama, which is roughly the open theatre condition, and for the post-Elizabethan drama, which is the proscenium condition. But these are merely labels. The real issue in spatial terms is what interests me as an architect, and what is there to be seen now, in the Olivier particularly, and in the Lyttleton, are the two visual and spatial relationships between actor and audience.

“In the Olivier room the action appears to be in your presence; you embrace it. In the Lyttleton you confront the action. They are totally different forms. Each of them can be very adaptable in their own form, but you can’t change the one form into the other unless you are prepared to change the walls, the ceiling and the floor.”

Idea and interpretation

Fortunately Lasdun was asked to design the National Theatre at a time when theatre ideas themselves were in a state of flux. Arena theatres, adaptable theatres and flexible theatre environments were very much in vogue and a lesser architect might well have been attracted to one of those ideas as the “with it” solution. Not so Lasdun. He encouraged the committee to erect a series of imaginative, hypothetical ideas which were interpreted in architectural terms by designing auditorium after auditorium until out of this process of idea and interpretation a solution gradually emerged.

Thus the original premise of a single national theatre gave way to a scheme incorporating three auditoria offering a flexibility undreamt of in the fifties. That in itself is a landmark in international theatre architecture.

A picture on the wall of Lasdun’s office shows the cast-off design models for the auditoria, thrown into a great heap; it also shows, claims Lasdun, “the relationship with the building committee”. He recalls the many dialogues that he and his partner had with the building committee: “We set out to search for the meaning of second-half 20th-century theatre in terms of actor/audience relationships. This was fundamental to our thinking and took about two years, which is what that photograph is about - trying to understand just what that meant before the design of any building at all. In fact the Olivier theatre is the nucleus. The whole building is generated by the Olivier and by that particular room.

“The building committee met every month. Everything they said was thought about, translated into model terms and re-discussed. The whole spatial feeling of course was not discussed - that’s an architectural matter. What they were searching for was discussed in terms of nobody feeling over or under-privileged - a sort of egalitarian theatre where everybody had a reasonable view and could hear properly. These were rather the mechanical sides of it.

“The issue itself was what was the dynamic of the theatre; what was the spirit of it? Should one have scenery, shouldn’t one have scenery? It was really going back to square one in terms of thinking and it was only after we had spent probably two years in finding out just what that did mean that we accepted the fact that there would have to be a proscenium theatre as well, and then after that an experimental theatre. The designing and the briefing were going simultaneously all the time. It was an enormous strain because we were dealing with intellectual matters, literary matters and theatrical matters, which had to be translated into architectonic terms.”

The intellectual problems took a long time to crack and the architects were all straining to the hilt to understand what all the discussion and experimenting meant architecturally. “Had we not had the confidence of what had been built up in our own past”, Lasdun says, “I don’t think we could have coped with it.” The team were convinced that “work on the design of the auditorium and the stage (the action area) was fundamental and had to come into existence before any architectural consideration from the outside of the building came into it”. The technological aspects of the design came later too. The early dialogues were uncluttered by the technology of the theatre.

Lasdun’s office had “a really good working relationship” with the stage machinery and lighting consultants and the mechanical, services and structural engineers who came in at a very early stage. Indeed, Lasdun sees the National Theatre as a very expressive building structurally: “The structure had to be considered very close to the architecture, and in fact when you move through the building you are primarily aware of the structure.”

Referring to the contractors, McAlpines, Lasdun said that “they played an extraordinarily important role… they put really first class people on the concrete…in fact the men behind the mixer and the men doing the batching and the men handling the shuttering did it with enor- mous skill…” There were however, inevitably, many difficulties which had to be overcome jointly with the contractors.

In Lasdun’s mind it is a traditional one-off building. “It’s an extremely difficult building, both for the architects and for the builders, it’s not repetitive in any way. It will be difficult in the future to build such a craftsmanlike building. Maybe a big shed with everything going on all over might be the new way of doing it. It doesn’t produce the same architectural results. Here you’re up against a very strong feeling in the office that architecture is not about technology, it is about space, and it isn’t about sculpture because you’re not so much looking at an object as actually moving through it.

“So that the experience of moving through space which compresses and expands and directs you and lights you as a complex arrangement is what we think of as architecture. It is not a flexible shed serviced on the outside. You could argue therefore that it’s a rather craftsmanlike building.”

Not the least of the problems that beset the architect, the contractor and indeed the management of the new theatre were the delays experienced during recent years. There seem to have been as many abortive opening dates for the National Theatre as retirement announcements for Frank Sinatra.

Many of the delays were, according to Lasdun, political. His office had to take a very responsible attitude to haphazard cut-backs and economies. “A great part of these delays was due to the constant monitoring of public expenditure and the time that was taken to redesign the building every time that someone said we had to cut £600,000 off, or another three quarters of a million - these were political figures. Somebody felt that it shouldn’t cost as much as it did and this meant overhauling the design three, four, five, six times. It’s been an enormous strain purely to keep the cost down. So far from being an expensive building, it is very low cost.”

Rock-bottom budget

Asked about the total cost of the National Theatre, Lasdun replied: “With all the knowledge. we had from the analysis of the quantity surveyor, that building is absolutely rock bottom budget, and it is one of the cheapest theatres in the world. It had rather less spent on it than a provincial theatre in Germany…it is a very, very low cost job.”

The low costs and the stringent economies have not, according to Lasdun, led to any diminution in the quality of the public spaces in the theatre, but on the other hand “the mechanical services have been dangerously cut and the comfort conditions inside the dressing rooms are possibly not so luxurious or as decent as they should be. The offices were done on a shoe string.”

Besides the nervousness about high capital cost buildings by successive governments and the GLC, a considerable amount of criticism has been made in the provinces about the concentration of so much talent and money in one centre in London.

Lasdun, who speaks as the architect of the building and not as somebody with a say in national theatrical policy, is sympathetic to this “very strong” regional argument. But he looks at it somewhat differently: “I think I’m right in saying that where the argument became unnecessarily severe, was in thinking that had there not been a national theatre the regional theatres would have got any more money.

“This would not have been the case. They would not have got the money that was voted to the National Theatre - it was only for the National Theatre. I regard the National Theatre as part of the regional theatre. I have never regarded the two things as mutually contradictory. I expect to see the regional theatres come to the National Theatre, and I expect the National Theatre to go out to the regions. There seems to me to be nothing wrong with England, whose genius excels in literature and drama, having a national home for what it’s very good at doing.”

Notwithstanding the broad cultural context in which Lasdun and his partners work, any discussion inevitably returns to the question of architecture and to the aims and responsibilities of the office. He concluded: “We are after all only the architects of the scheme. Given the National Theatre to do, the prime task was to give them what we think was wanted. We’ve done our best to do that and within the cost. That is the task of an architect.”

asda

No comments yet