In the first of our series of archive articles celebrating our 180th anniversary, we unearth an editorial from 1847 on the construction of the Houses of Parliament

This year marks the 180th anniversary of Building, and to celebrate we are publishing an article from the archives each week. Building, first launched as The Builder in 1843, is one of the world’s oldest surviving trade publications. It started life at a time of huge national confidence, when Britain was the world’s leading industrial power, and when revolutionary new construction techniques were expanding the possibilities of what buildings could look like.

This piece, from April 1847, documents the construction of the Houses of Parliament. Written during the editorship of George Goodwin, it is glowing in its praise of the design of the new building, which it describes as “most satisfactory”.

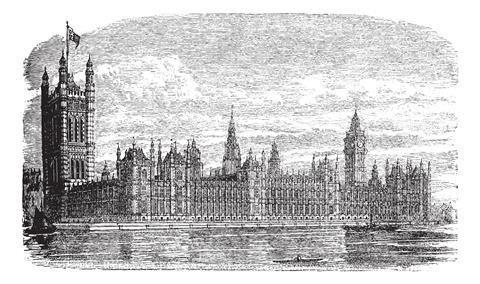

The medieval palace on the site had been largely destroyed by fire in 1834, sparing only Westminster Hall and a few smaller buildings including the Jewel Tower. Rebuilding the complex would become one of the most ambitious projects of the century. Designed by Charles Barry and Augustus Pugin, its construction started in 1840 and was not fully complete until 1876.

This extract from the editorial is partly a rebuke to criticisms of the slow progress of construction, and an explainer on the individual contracts for the work. It was written in the same year that the Lords Chamber, one of the most ornate parts of the complex, was completed.

Editorial in The Builder, 17 April, 1847

One portion of the most important building now going on in Europe is completed, with the exception of some intended frescoes, and the stained glass in the windows; and before the present number of our journal reaches the public, will have been occupied by that branch of the legislature for whose use it is intended.

As an example of what the whole structure, or rather pile of structures will be when finished, it is most satisfactory, and may be appealed to with confidence as an evidence of the constructive and artistic ability existing in England. There is nothing like it amongst us. It stands by itself; and cannot fail to have a great effect on the arts of the country.

The extent of the new “Palace of Westminster,” is not understood by those who, passing on their way, gaze on the elaborately carved façade presented to the river, nor fully appreciated by the majority of visitors, even, who penetrate the inclosure [sic], and pass with sight-seeing eyes around its length and breadth. It needs a longer acquaintance, a careful examination of it part by part, an ascent of scaffoldings, inspection of the means in operation, and comparison with other buildings, before the greatness of the work can be perfectly understood.

When a knowledge of this is fully acquired, the absurdity of complaints made by those who ought to know better, against the slow progress of the building, and reflected in the doggrels of burlesque, where “Barry” was made to rhyme with “tarry,” at once becomes apparent; and every intelligent mind must feel astonished that so much has been done so well, in the time that has elapsed since the commencement of the works.

The delay that was caused in respect of the ventilation, and the difference between working for an individual and working for Government, from whom decisions are sometimes not to be obtained for weeks, must also be remembered, and the surprize will be still further increased. Remember, the building covers nine acres, and has a frontage of nine hundred feet; that there are eleven open courts, and that the highest tower, to which we must refer again hereafter, will be 346 feet high.

As to an architect’s own power of production, that seems never to enter the mind of the public. As we said in an article written in the middle of 1845 (when some of the peers were pressing forward the works unduly), and which, as we were informed at the time, had a beneficial effect, “Some persons think, if we may use the word where no thought is really given, that when an architect has produced the design for a building his work is over, and that it may, without further thought, be forthwith carried out. Nothing is more erroneous, especially as regards Gothic architecture; it is then that the architect’s labour commences, and his skill is proved.

In such a work as the Houses of Parliament, every superficial yard demands the closest thought, and requires as many detailed drawings, in some cases, as for the whole of an ordinary dwelling-house. Every ornament, every moulding, every line, must be produced and delineated; and over all these does Mr. Barry’s pencil pass. An architect careless of his reputation may get through any amount of work, by deputy; but if determined to execute it to the best of his power, strive as he may, he can only produce a certain quantity; and we will venture to say, that the architect of the new Houses of Parliament finds little time for other occupations or for recreation, from early on Monday morning till late on Saturday night. The wear and tear must be immense.

The life of an architect, even under favourable circumstances, is one of toil and anxiety; and he needs to have no extraneous circumstances to harass and perplex him. We have heard a member of the lower House declare his ability to write poetry by the mile; we may probably find one of the upper House profess the power to design Gothic details by the acre, and laugh at the idea of limits to a man’s power in so simple a matter. They would be equally entitled to credence; we should merely say they were exceptions from the general rule.

Our present immediate business is with that part of the new Houses of Parliament which is finished, namely, the House of Lords; a view of which, taken from the north end of the House, below the “bar,” will be found in our present number; but we think it desirable to let this article treat of the building generally, and record briefly, for future reference, the progress of the works.

The foundation of the building next the river was commenced in 1839, by Messrs. Lee, of Chiswell-street. Messrs. Grissell and Peto undertook the first contract for the superstructure of the new Houses in 1840. It comprised the range of buildings fronting the river, with the returns next Westminster-bridge and at the south end towards Abingdon-street.

This building includes the residence for the Speaker at the north end, the corresponding terminal towards the south being the residence for the Usher of the Black Rod. Between the two extremes, and comprising what are called the curtain portions, are the libraries for the House of Peers and the libraries for the House of Commons: in the immediate centre is the conference-room for the two Houses. All this is on the principal floor, which is some 15 feet above the terrace, or high-water mark.

The whole of the floor above the libraries, and overlooking the river, is appropriated to committee rooms for the purposes of Parliament, the Peers occupying about one-third towards the south, and the Commons two-thirds towards the north. The House of Peers and House of Commons are situated in the rear of the front building, or that next the river, and will, when completed, be inclosed also towards the west, so as to be entirely surrounded by Parliamentary offices.

The second contract, also undertaken by Messrs. Grissell and Peto, comprised the House of Peers, the House of Commons, the Victoria Hall, the great Central Hall, the Royal Gallery and Commons Offices, next Palace-yard, and the Clock Tower, next Bridge-street. This was the second contract undertaken by Messrs. Grissell and Peto, but in Parliamentary votes, (we may mention it, in ease our readers should hereafter refer to them), it is called contract No. 5.

The third contract was St. Stephen’s Hall and Porch, extending from the Central Hall at right angles, and communicating with the south end of Westminster Hall, and having a principal entrance also, opposite St. Margaret’s Church and Poet’s corner. This contract which is now in progress is called No. 6.1

Contract No. 7 comprises the fittings of the entire building, and has been undertaken by Mr. Grissell alone, Mr. Peto, who was concerned jointly with Mr. Grissell in the previous contracts, having retired from the building business.

The plan of the building is exceedingly simple and beautiful

Contract No. 5 is expected to be completed in the course of the present summer. No. 6 will be completed by the end of the present year, as far as the carcase is concerned, and the contract No. 7, for the fitting and finishing of the whole building, can scarcely tail to occupy the next four or five years. It will be seen from this, that with the exception of a portion of the foundation, the whole of the contract works have been undertaken by Messrs. Grissell and Peto, and are now in the hands of Mr. Grissell.

Confining ourselves for the present to generalities, the plan of the building is exceedingly simple and beautiful. From the Central Hall, an octagon of 70 feet, a corridor to the north (to your right, if you stand with your back to the Thames), leads to the Commons’ Lobby and Commons’ House; and a corridor to the south, to the Peers’ Lobby, one of the chambers completed, and the House of Peers. Opposite to the spectator (still standing as before) is St. Stephen’s Hall and Porch, communicating, by noble flights of steps, with Westminster Hall, and forming an approach of unequalled magnificence.

It is worthy of remark, that when the floor of St. Stephen’s Hall is reached, there is no one step throughout the whole extent, all is of one level. In a line with the House of Lords, still further to the south, are the Victoria Hall (now finished), the Royal Gallery (a noble apartment, 108 feet. long, 45 feet wide, and 45 feet high, to be filled with paintings and sculptures), and the Queen’s Robing Room, communicating with the Royal Staircase and Tower at the southwest corner of the pile, now rearing itself in Abingdon-street.

The construction of the building throughout is externally of magnesian limestone from North Anstone, in Yorkshire, near Worksop, Notts. It is a beautiful close grained stone, of a texture considerably harder than Portland, and somewhat warmer in colour. The interior parts of the walls are of hard burnt Cowley stocks, exclusively from the fields of Mr. Westbrook, of Heston, which are admitted to be the best manufactured of any that are made for the London market. The bearers of the floors are of east-iron, with brick arches turned from girder to girder; the entire roofs are of wrought-iron covered with cast-iron plates galvanized; the gutters are also of cast- iron galvanized; so that the carcases of the entire buildings are fire-proof, not any timber having been used in their construction. Wrought-iron bond, in courses of brickwork in cement, is used throughout all the walls.

>> Also read: News in pictures: original home of House of Commons restored

>> Also read: Palace of Westminster: the mother of all refurbishments

>> Also read: Full decant for repairs of Parliament will save billions

No comments yet