Building reported the official opening of the controversial project and wondered what the world would make of it

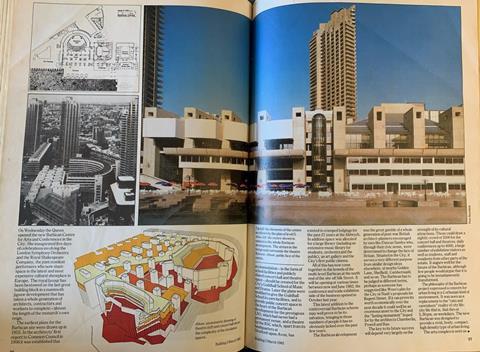

The Barbican Centre was built on five-and-a-half acres of bomb-damaged ground. It cost the rough equivalent of £500m to complete and London’s expensive postwar gift to the nation experienced a mixed reception.

Construction work began in 1965 and finished 11 years later, forming the final phase of the Barbican Estate, which comprises around 2,000 residences. The centre was inaugurated by Queen Elizabeth II in March 1982. She described it as “one of the wonders of the modern world”.

Although the building has now become a symbol of London’s performing arts scene, its brutalist 1970s design and ziggurat facade was met with criticism. Despite earning grade II listed status in 2001, it was voted “London’s ugliest building” in 2003 by a Grey London poll, echoing disdain from previous decades.

Western Europe’s largest arts centre is famed for its concert hall, where the London Symphony Orchestra and BBC Orchestra are based. The venue was re-engineered in 1994 in response to complaints that the acoustics were too dry for large-scale performances, despite others enjoying its auditory warmth.

Throughout its life, the Barbican has undergone refurbishments and upgrades, from the addition of statues and decorative features in the mid-90s, to bold signage and improved circulation in 2005-2006.

On Wednesday the Queen opened the new Barbican Centre for Arts and Conferences in the City. She inaugurated five days of celebrations involving the London Symphony Orchestra and the Royal Shakespeare Company, the joint resident performers who now share space in the latest and most expensive cultural showplace in Europe. The royal favour has been bestowed on the last great building block in a mammoth jigsaw development that has taken a whole generation

of architects, contractors and workers to complete - almost the length of the monarch’s own reign.

The earliest plans for the Barbican site were drawn up in 1955. In the architects’ first report to Common Council in 1956 it was established that accommodation - in the form of school facilities and publicly shared concert hall and theatre space - should be created for the City’s Guildhall School of Music and Drama.

Later the plans were modified to give the Guildhall School its own facilities, and to provide public concert space in the heart of the Barbican development for the prestigious LSO, which had never had a permanent venue, and a theatre for the RSC which, apart from its headquarters at Stratford-upon-Avon, has existed in cramped lodgings for the past 21 years at the Aldwych. In addition, space was allocated for a large library (including an extensive music library for students, orchestra and the public), an art gallery and the City’s first public cinema.

All of this has now come together in the bowels of the multi-level Barbican at the north end of the site off Silk Street. It will be opening at various times between now and June 1982; the conference and trade exhibition side of the business opened in October last year.

This latest addition to the controversial Barbican scheme may well prove to be its salvation, bringing in those numbers of people it has so obviously lacked over the past few years.

The Barbican development was the great gamble of a whole generation of post-war British architect-planners encouraged by men like Duncan Sandys who, through their civic sense, were determined to change the face of Britain. Situated in the City, it serves a very different purpose from similar design ideas elsewhere, at nearby Golden Lane, Sheffield, Cumbernauld, and so on.

The Barbican has to be judged in different terms, perhaps as someone has suggested like Wren’s plan for the City or Nash’s proposals for Regent Street. If it can prove its worth economically over the next decade it could well be an enormous asset to the city and the “lasting monument” hoped for by the architects Chamberlin, Powell and Bon.

The key to its future success will depend very largely on the strength of its cultural attractions. These could draw a nightly crowd of 3500 for the concert hall and theatres, daily conferences up to 4000, a large number of exhibition visitors as well as students, staff and residents from other parts of the estate. It augurs well for the future of the Barbican, although few people would argue that it is going to be instantaneously transformed.

The philosophy of the Barbican project expressed a concern for urban living in a Corbusian kind of environment. It was seen as a replacement to the “cats and caretakers” reality of city life: city life that is, that dies at 5.30 pm, on weekdays. The new Barbican was designed to provide a vivid, lively, compact, high density type of urban living.

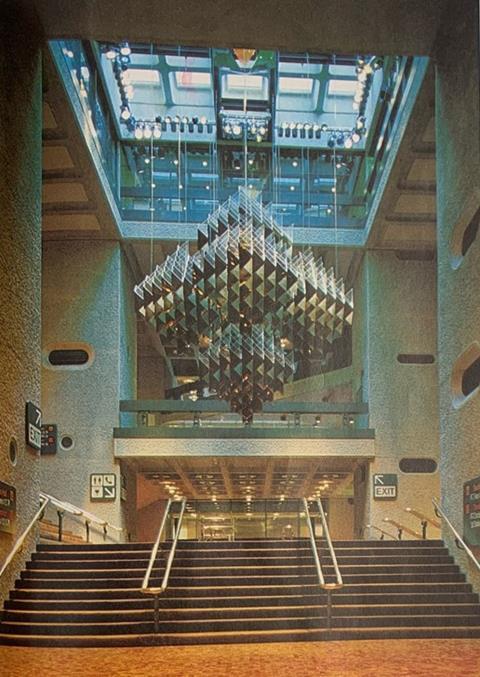

The arts complex is seen as a binding element in the City’s new urban mixture. Locked into a vast subterranean area of multi-use spaces and held in a rigid rectangular grid of structural supports the two new public halls share a common foyer area. This circulation space is approached from two sides of the site with the north entrance reserved largely for taxis and pedestrians and the lower level south one for setting down from patrons’ own vehicles.

Once inside, the visitor is presented with two bulky building elements, a brightly coloured painted surface that defines the concert hall and the “external” street-like facade of the Barbican Theatre. Stairs and lifts take the visitor down to “The Pit” and the cinema, or up to the fresh air of the lakeside promenade and the many restaurants.

Of the two auditoriums the aisle-less theatre is the more interesting. It accommodates an audience of 1160 in specially widened rows of “continental” seating approached through individual doors on either side of the shallow interior. This unique design idea eliminates circulation space from inside the theatre.

Externally, small stepped foyers lead to the individual doorways. The bonus provided by this compactness is good sight lines for every seat in the house with none further away than 65 feet from the point of command. The 73-foot stage is an open one but flexible enough to provide a proscenium stage, whenrequired, of 44-foot width. The three balconies above are drawn into the compact concave of the theatre’s section and project forward towards the stage rather than backwards as at the RSC’s home at Stratford.

The mechanical guts of the theatre are housed in a huge fly tower which not only gives the stage a “double height” but acts as a giant tentpole for the ambitious conservatory on the arts centre’s roof. At this level things come together by a process that can only be called serendipity; left-over space that the engineers and architects had at their disposal has been transformed into a spectacular winter garden.

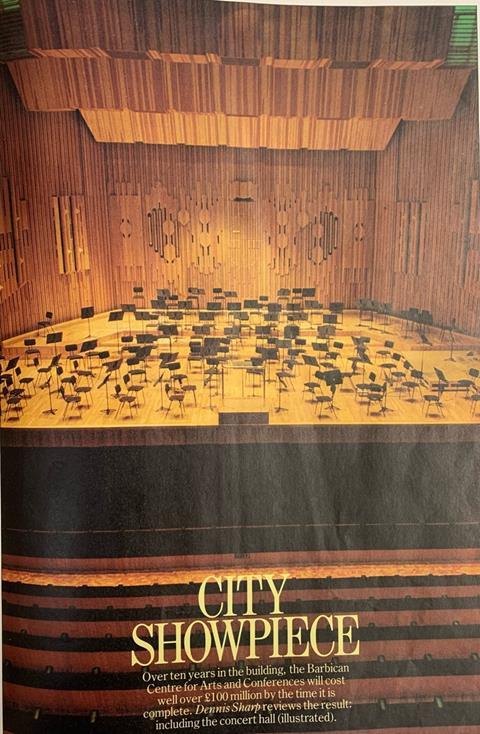

The concert hall appears less innovative. It is, however, impressive in its layout providing a large, clear space for an audience of 2000 and an orchestra of 120 players; it can also be adapted to accommodate a large choir as well as daily conferences.

Unfortunately, the plan to provide a large pipe organ was dropped (on the assumption that other venues would be used for organ works), but the warm-coloured internal woodwork which surrounds the platform is treated in a sculpted and organ-like manner in order to bring this important area into focus. Sound is, however, the key factor in a large concert hall such as this. From the reports received so far the acoustics are successful but this cannot be confirmed until a whole range of musical works have been performed.

The Other Place has proved to be a much liked, small experimental theatre for the RSC. Situated in The Warehouse in Covent Garden it has attracted a rather special and enthusiastic local, rather than tourist, audience. This theatre will now be repositioned in an irregular shaped space under the Barbican Theatre. Its Poe-sounding name, The Pit, is entirely appropriate to its almost secret location and black decor, dreamt up by Trevor Nunn himself.

Adjacent to The Pit is the 280-seat cinema which, when it was originally designed by the late Joe Chamberlin, promised to be a rather special place with banks of lounge seats, angled screen, and mid-auditorium projection. Now it has been conventionalised; and festooned with hanging television monitors and “enlivened” by rows of multi-coloured seats. Two other cinemas, seating 250 and 150 people respectively, are available for private booking.

The opening exhibition in the spacious two-level art gallery is one partially created by the Centre Pompidou on French Art in the post-war period, 1945-54. At least this suggests that the gallery may well have an international bias in its selection of future exhibits, although it does not explain why on such an auspicious occasion as this it has not produced something more original and at least residually British.

Indeed, this will be part of the price that the administrators and conference organisers will have to pay if the centre is to succeed. It could be sold as a venue of one of the world’s great orchestras, hired as usable space or even “sold” in architectural terms like the Sydney Opera House. It would be very sad if its multiple uses, urbane quality and flexibility were ever compromised. They are as profoundly a part of the architects’ original intention as the monumental modernism of its multi-layered and complex layout. The Barbican is indeed the brainchild of the 1950s, but through a difficult upbringing it has now reached maturity.

More from the archives:

>> Nelson’s Column runs out of money, 1843-44

>> The clearance of London’s worst slum, 1843-46

>> The construction of the Palace of Westminster, 1847

>> Benjamin Disraeli’s proposal to hang architects, 1847

>> The Crystal Palace’s leaking roof, 1851

>> Cleaning up the Great Stink, 1858

>> Setbacks on the world’s first underground railway, 1860

>> The opening of Clifton Suspension Bridge, 1864

>> Replacing Old Smithfield Market, 1864-68

>> Alternative designs for Manchester Town Hall, 1868

>> The construction of the Forth Bridge, 1873-90

>> The demolition of Northumberland House, 1874

>> Dodging falling bricks at the Natural History Museum construction site, 1876

>> An alternative proposal for Tower Bridge, 1878

>> The Tay Bridge disaster, 1879

>> Building in Bombay, 1879 - 1892

>> Cologne Cathedral’s topping out ceremony, 1880

>> Britain’s dim view of the Eiffel Tower, 1886-89

>> First proposals for the Glasgow Subway, 1887

>> The construction of Westminster Cathedral, 1895-1902

>> Westminster’s unbuilt gothic skyscraper 1904

>> The great San Francisco earthquake, 1906

>> The construction of New York’s Woolworth Building, 1911-13

>> The First World War breaks out, 1914

>> The Great War drags on, 1915-16

>> London’s first air raids, 1918

>> The Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building, 1930

>> The Daily Express Building, 1932

>> Outbreak of the Second World War, 1939

>> Britain celebrates victory in Europe, 1945

>> How buildings were affected by the atomic bombs dropped on Japan, 1946

>> Rebuilding the House of Commons chamber, 1945

>> Planning the postwar New Towns, 1945-46

>> The Festival of Britain, 1951

>> The world’s first nuclear power station, 1956-57

>> Building covers the 1964 election

No comments yet