Building charts the early years of what would become one of the world’s largest commercial districts

The transformation of the Isle of Dogs into one of the largest commercial districts in the world was arguably the biggest UK construction story of the 1980s. Mentioned in one form or another almost every week in the pages of Building, its creation was an epic saga which came to define the decade’s economic revival – and its boom and bust culture.

What had once been one of the busiest docks in the world, the West India Docks, was closed in 1980, a victim of the containerisation which revolutionished shipping after the Second World War. The London Docklands Development Corporation (LDDC) was created in 1981 to rethink the area, and the land surrounding the docks was designated an enterprise zone the following year, with a number of tax breaks intended to attract investors.

Several years of wrangling followed and construction was not to start until 1988, after the project had been sold to Toronto-based Olympia & York, then the largest property development company in the world. It quickly proved to be a poison chalice, with a slump in London’s commercial market at the end of the decade contributing to the firm’s collapse in 1992, a year after the completion of what is still Canary Wharf’s most famous building, the Cesar Pelli-designed One Canada Square.

Below is a series of news, feature and comment articles published in Building covering the early years of the project, culminating in the release of the first detailed images of what the new commercial district would look like. “It is not offensive and perhaps that is as much as can be hoped for,” was Building’s weary assessment of the postmodern Beaux Arts style chosen.

News item, 16 April 1982

First sites on offer in London’s enterprise zone

The London Docklands Development Corporation has announced that it is marketing the first commercial development opportunities in the 195-hectare Isle of Dogs Enterprise Zone. The corporation, which is also the landowner, is offering through agents more than 13 hectares adjoining Millwall Dock and the proposed production plant for the Daily Telegraph, and opposite its own headquarters.

Three major sites totalling almost 54 hectares are destined for speculative development by companies and investors. The largest of 2-4 hectares is earmarked for business uses of between 370 and 1840 square metres; a 1.6 hectare site will provide for institutional units from 322 square metres, and a third will cater for small business units. The remaining 8 hectares are scheduled for industrial, warehousing or office owner occupiers, and individual units will be on offer from a minimum 0.2 hectare.

All the sites will be fully serviced and the corporation is soon to start construction of a new access road to serve the area.

Ever since the Government announced its commitment to the concept of enterprise zones and indicated the financial inducements that would be on offer to attract new business into the 11 chosen areas, sceptics have stressed the two risks inherent in the new approach. Land values, they said, would automatically rise, off-setting the values of rated exemption, capital allowances, long ground leases without rent reviews, and other benefits available. Second, it was predicted that the zones would generate little new activity, merely redistributing existing firms.

The corporation refuses, however, to be drawn on what land values it is seeking for these sites. “Land values”, it says, “have yet to be established but will have to absorb the Corporation’s keenness to see high-quality development and occupiers.”

The question now is whether, when the offers come in, the Corporation will hold out for its own valuation of the land, taking account of the financial benefits available, or whether it will be prepared to see a much lower return to get development off the ground. Before this latest exercise, there were already reports of developers considering new investment in the zone being faced with price demands which seemed nearer prime industrial land values than the realities of a location as off-beat as the Isle of Dogs.

There is bound to be plenty of interest in London’s only enterprise zone. The rates remissions alone are highly attractive to any London businessman. Even before the agents were instructed, the LDDC claims to have had 600 enquiries about the zone, a quarter of them seeking the type of space which is now being planned, although the zone will not even be designated until later this month.

Such potential demand only underlines the need for the corporation to be flexible about the land values issue. London is awash with vacant industrial space and virtually every borough is pushing through new industrial estates, and that latest municipal virility symbol, technology “science parks”.

The Isle of Dogs needs some early successes in commercial development if the momentum established by the new Billingsgate Market and the Daily Telegraph plant is to be sustained. Some of the more grandiose projects paraded for the zone last year, for example the £200 million high technology Thames Island project, in which Balfour Beatty has an interest, have found the LDDC somewhat less welcoming than expected.

Docklands’ history is littered with grandiose projects that have failed to get off the ground, and the corporation’s modest start with a mixed development package clearly makes sense in marketing terms. It will do little, however, to allay the boroughs’ fears that the enterprise zone will merely redistribute existing businesses from elsewhere in north east and south east London.

The boroughs will be hoping that the rolling programme being worked out for the rest of the island zone will concentrate more on innovative enterprises and less on beggaring its run-down neighbours.

News item, 28 May 1982

Isle of Dogs Zone launched

Britain’s 11th and final enterprise zone – so far – was officially launched last Friday by the Chancellor of the Exchequer when 3,000 red, white and blue balloons sailed into the sky above London’s Isle of Dogs.

Back on the ground, Nigel Broackes, chairman of the London Docklands Development Corporation, reported that bids for the first sites, due in later that day, included food manufacturers, a pharmaceutical company, a firm of mirror makers, plastic manufacturers and a company engaged in the production of computer hardware and software systems.

The first six blocks of land on offer have covered some 30 acres (out of a total of about 480, including 120 water) opposite the LDDC offices on the west side of the inner Millwall Dock.

“Present indications are that the offer is already fully subscribed, in which case I would expect to have them all signed up in a month or two, with construction starting later in the year and people beginning to move in by the end of next year,” Mr Broackes said.

Mr Broackes also announced that the Daily Telegraph proposals for more than 250,000 square feet of newspaper plant opposite Millwall South Dock would somewhat resemble an ocean liner and that there would be provision for newsprint to be delivered by water.

London’s enterprise zone was formally designated on 26 April, which is the date from which the ten-years’ local rates holiday begins, as does the exemption from development land tax and the special capital tax allowances. The LDDC chairman pointed out that while the latter were attractive to some investors, they were of little use to pension funds and insurance companies, which normally paid little, if any, tax.

“In the zone itself, it’s the banks who can probably offer the best value,” he said. “It’s the leasing subsidiary of one of the joint stock banks which has completed one of the first financial packages here and I commend it to anyone who is interested.” Afterwards Sir

Geoffrey Howe sketched in something of the history of enterprise zones, which he put forward as an idea less than four years ago in a speech to the Bow Group at the Waterman’s Arms on the Isle of Dogs. In the meantime, 11 appeared on the ground in Britain, having been taken up by local authorities of both party colours.

In this country, in Clydebank, 82 firms with the potential of 950 new jobs have moved in to set up or expand and of these 32 were new ventures, he said. In Swansea, 47 firms had moved in or set up in the zone, including seven new ones. In Corby, nearly half the land was committed and the New Towns Commission was letting advance factories units as fast as it put them up.

News item, 25 July 1986

Site works start on Canary Wharf

Preliminary site works began this week on the £2bn Canary Wharf banking centre in London Docklands. Building work is being carried out by a joint venture comprising Costain, Laing, Mowlem, Taylor Woodrow and Sir Robert McAlpine.

Works being carried out include general site clearance, diversion of services, stabilisation of quay walls, site investigations and test borings and the erection of site offices.

The work is being undertaken under licence of the London Docklands Development Corporation, which owns the site.

News item, 19 June 1987

Setback on Canary Wharf

Backers of the Canary Wharf development suffered a series of setbacks this week with rumours that essential rail link improvements would be dropped unless the master building agreement is signed by next Monday.

This fuelled further speculation that the LDDC would approach a Canadian developer, Olympia and York, if the Canary Wharf Development Consortium proposals were not finalised shortly.

The consortium also came up against strong all-party opposition at the London Borough of Tower Hamlets where a policy sub-committee clashed with the developers over road schemes.

Feature, 2 October 1987

London Docklands: The next five years

With growing harmony between the left-wing borough councils and those rebuilding London Docklands, Russell Steadman looks at LDDC’s five-year plan:

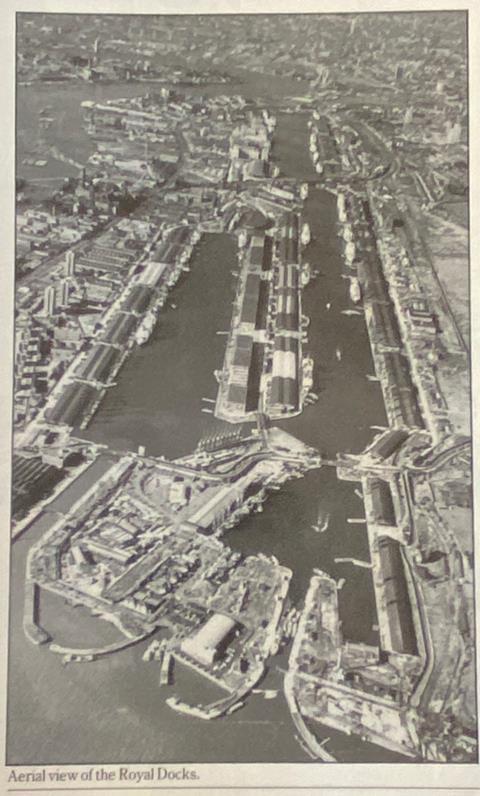

After six years of wrangling. Labour-controlled Newham Council and the London Docklands Development Corporation this week reached agreement on the redevelopment of the disused Royal Docks.

In return for council approval for infrastructure works and roads, the corporation will seek to ensure that 1500 homes are built either for rental or for sale at a low cost.

The council is hoping that up to £100m can be obtained from the corporation and developers for social and economic benefits. The two parties will also try to ensure that 25% of new jobs in the borough will go to local people.

Christopher Benson, chairman of the LDDC, says: “We are now in a position to invest more in social initiatives to ensure social gain for local people.”

Newham’s chair of planning, Councillor Stephen Timms, says: “Although problems remain with the LDDC plans, if the corporation’s board backs this agreement I am confident that there will be very substantial benefits for Newham. It will no longer be a case of the community being pushed aside.”

This significant agreement coincides with the launch of the LDDC’s corporate strategy outlining its thinking on development in the docks over the next five years.

Between April 1988 and March 1993 the LDDC will spend £531m on programme works including major road schemes as well as other infrastructure projects such as drainage and site clearance.

Over the five years the corporation will spend an additional £39.3m on land acquisition, mainly “in support of the corporation’s highway proposals, and to buttress regeneration proposals elsewhere, especially in the Royal Docks area”.

The road building programme will account for £102m of the LDDC’s expenditure, with major schemes in the Isle of Dogs and Leamouth (£63m) and Wapping and Limehouse (£39m).

In the Royal Docks the LDDC expects to spend £203m at the rate of £49.7m and £48.9m in the first two years. In 1990-91 expenditure will fall to £41.3m, with the remaining £63.6m to be spread over the last two years. These figures include spending on major roads in the area, site clearance and drainage. The plan assumes that much of the site infrastructure will be funded by developers carrying out large-scale schemes.

Schemes in the area include a Laing/Fox/Vom proposal to build a 25,000-seat stadium, an 18,500m2 exhibition hall together with 120,000m2 of space for offices, businesses and leisure, and 1,750 homes, on the north side of the Royal Victoria Dock. On the south side of the dock Conran Roche/Heron/Mowlem are planning to develop 3,000m2 of retail space, with 5,000m2 of offices and 1,630 homes.

A 230,000m2 science and commercial park is included in the proposal by Rosehaugh Stanhope for the Royal Albert Dock. The LDDC has allocated £15.7m to spend on social infrastructure projects in the area during the five years.

In the Isle of Dogs the LDDC will spend £107.4m between 1988 and 1993 with £33.7m and £32.4m allocated for the first two years respectively. Expenditure will then fall to £23.4m in 1990-91 with £17.9m spread over the last two years. A major road building programme will require £69.8m over the five-year period, with another allocated £30.8m for social infrastructure.

In Wapping and Limehouse, the Docklands areas closest to the City, where the population is expected to more than double over the next five years, the LDDC will spend £6.9m over the period.

An additional £40m will be spent on the Limehouse link road and for social infrastructure: “School and adult education facilities, new and upgraded parks and open spaces, plus enhanced shopping and leisure facilities are planned for implementation,” says the report.

On the South Bank of the Thames in the Surrey Docks, the corporation will spend £18.9m over the five years, with £6.7m and £5.4m spent in the first two years, £1.6m in 1990-91 and the remaining £5.2m spread over the last two years.

“Last year some 70% of corporation investment in the Surrey Dock area was in infrastructure. This year the same proportion of investment will be on superstructure and its maintenance.”

By the year 2000 a total of 2.6 million square feet of commercial space will have been completed in Docklands, while in 1991 there will be over 15,000 construction workers employed in Docklands.

News item, 1 April 1988

Pelli takes Manhattan to the Isle of Dogs

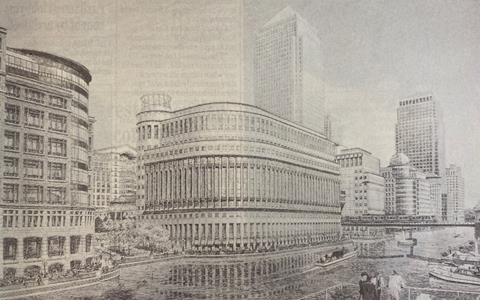

A strong American flavour is evident in the detailed architectural designs for the £4bn Canary Wharf development in London Docklands, which were revealed this week. The first phase takes the form of a sleek 240m high skyscraper shaped like an obelisk, set amid a dense collection of medium-rise blocks in a medley of turn-of-the-century Beaux Arts styles.

The skyscraper, which would be the tallest building in Britain, is designed by American superstar architect, Cesar Pelli. Pelli recently completed similar blocks in New York’s Battery Park City, which, like Canary Wharf, is developed by Olympia & York of Toronto. Three sets of associate architects and consultants are also involved in the Canary Wharf skyscraper: Adamson Associates from New York, Frederick Gibberd Coombes & Partners and Building Design Partnership, both from London.

Pelli says that he has set out to create “a rather archetypal vertical form, a square prism culminating in a pyramid against the sky. This is the form, of course, of an obelisk”.

He has narrowed the cladding materials down to two options - stainless steel or red granite. Stainless steel would shine or gleam in the light, while granite would be more monumental, argues Pelli. In either case, all external walls and the roof would be clad in the same material “to strengthen the simplicity and dignity of its form”.

The general site planning has been designed by American architects Skidmore Owings & Merrill and landscape architects Hanna/Olin. SOM says the buildings will relate to each other, with each retaining its own distinct architectural character.

Instead of sheer, featureless curtain walling, a grand Beaux Arts style, typical of turn of the century American cities, has been favoured. Traditional framed windows have been emphasised, while facades are vertically sub-divided into a classical format of base, central shaft and cornice. Classical rustication in heavy stonework is featured at ground level.

Hanna/Olin has designed three major open courts and include several thousand mature trees to line the edge of the scheme. The plan has been welcomed by Canary Wharf consultant Sir Roy Strong.

Comment, 8 April 1988

A question of style

The great public debate on architectural style continues to rage. This week alone we have seen violent disagreements on the validity of the environment department’s list of listed post-war buildings, a fascinating debate in the House of Lords on the subject, and the unveiling of the Canary Wharf designs in Beaux Art style.

By far the most important event must be Canary Wharf. Although we have been criticised for concentrating too heavily on this one scheme, Canary Wharf is having and will continue to have enormous influence on the entire UK property and construction scene.

The scale and intensity of the development inevitably dominate. Future generations will judge whether the rush to build was wise, but for those trapped in the spiral of ever-rising London office rents, the prospect of a freer commercial market must appeal.

Stylistically, Canary Wharf appears more leaden than exciting. But it is not offensive and perhaps that is as much as can be hoped for. What will make the scheme rise above a mere tatty speculative development will surely be the quality of finishes in the public areas.

The model for Canary Wharf should be New York’s Rockefeller Centre which today, 50 years, after it was conceived and built, remains a model of the way humanity can be brought to even the largest development.

More from the archives:

>> Nelson’s Column runs out of money, 1843-44

>> The clearance of London’s worst slum, 1843-46

>> The construction of the Palace of Westminster, 1847

>> Benjamin Disraeli’s proposal to hang architects, 1847

>> The Crystal Palace’s leaking roof, 1851

>> Cleaning up the Great Stink, 1858

>> Setbacks on the world’s first underground railway, 1860

>> The opening of Clifton Suspension Bridge, 1864

>> Replacing Old Smithfield Market, 1864-68

>> Alternative designs for Manchester Town Hall, 1868

>> The construction of the Forth Bridge, 1873-90

>> The demolition of Northumberland House, 1874

>> Dodging falling bricks at the Natural History Museum construction site, 1876

>> An alternative proposal for Tower Bridge, 1878

>> The Tay Bridge disaster, 1879

>> Building in Bombay, 1879 - 1892

>> Cologne Cathedral’s topping out ceremony, 1880

>> Britain’s dim view of the Eiffel Tower, 1886-89

>> First proposals for the Glasgow Subway, 1887

>> The construction of Westminster Cathedral, 1895-1902

>> Westminster’s unbuilt gothic skyscraper 1904

>> The great San Francisco earthquake, 1906

>> The construction of New York’s Woolworth Building, 1911-13

>> The First World War breaks out, 1914

>> The Great War drags on, 1915-16

>> London’s first air raids, 1918

>> The Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building, 1930

>> The Daily Express Building, 1932

>> Outbreak of the Second World War, 1939

>> Britain celebrates victory in Europe, 1945

>> How buildings were affected by the atomic bombs dropped on Japan, 1946

>> Rebuilding the House of Commons chamber, 1945

>> Planning the postwar New Towns, 1945-46

>> The Festival of Britain, 1951

>> The world’s first nuclear power station, 1956-57

>> Building covers the 1964 election

>> Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral, 1967

>> The new London Bridge, 1973

No comments yet