Building looks into how Rosehaugh, Stanhope and Bovis managed to build the first two phases of the now redeveloped City estate so quickly

British Land’s 32-acre Broadgate development on the northern edge of the City of London has become synonymous with the capital’s 1980s revival. Built using innovative construction techniques imported from the US, it revolutionised Britain’s construction sector and domestic expectations around how quickly large schemes could be built.

The first two phases were completed in just 12 months, ready in time for the Big Bang on 27 October 1986, the much-anticipated deregulation of financial markets which supercharged the growth of London’s financial services sector.

Below is a feature in Building published on 11 July that year looking into how developers Stanhope and Rosehaugh, contractor Bovis and Arup Associates architect Peter Foggo finished the project so quickly.

Feature in Building, 11 July 1986

BROADGATE AT THE DOUBLE

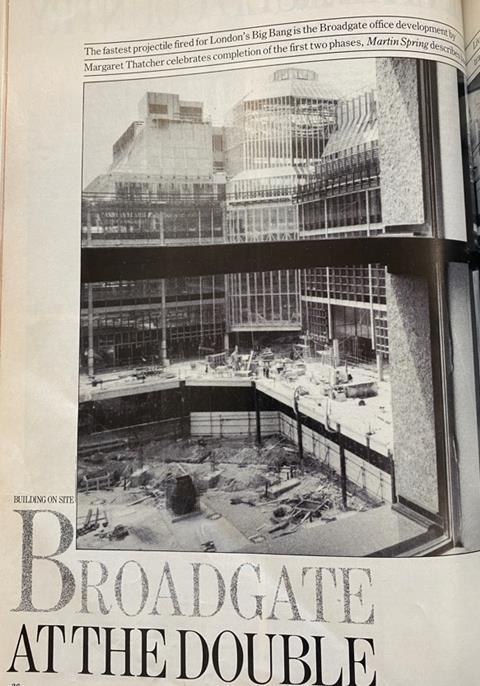

The fastest projectile fire for London’s big bang is the Broadgate office development by Liverpool Street station. Today, as Margaret Thatcher celebrates completion of the first two phases, Martin Spring describes how track construction was carried out.

Last year’s winner of the Financial Times architecture award, No 1 Finsbury Avenue, set a record for speed of construction, with its shell and core completed in only 15 months, ready for tenants’ fitting out.

The first two phases of the Broadgate development next door are roughly twice the size, some 68,000 m2, yet have been completed in only 12 months. It is no coincidence that the two office schemes have developer Stuart Lipton and the multi-disciplinary design team Arup Associates in common.

In intention, the breakneck speed of the Broadgate development is to provide financial trading floors and office space in time to service the City’s Big Bang on 26 October this year. In practice, however, the development team was able to hand over the first phase building to the tenant for fitting out a full four weeks ahead of schedule, with the second phase also being handed over two weeks early. By mid-June this year, the date originally agreed for handover, the first phase tenant had already completed £1 million’s worth of fitting out.

American inspiration

The open secret at Broadgate is that the fast construction methods - like the American. Express and Security Pacific banks that will be occupying the first two phases - are American in origin. Admiration for American attitudes, as well as experience in their techniques, radiates from developer Stuart Lipton, from his project director, Peter Rogers, and from lan Macpherson, project director of the construction management firm Bovis. For good measure, the Chicago-based construction management firm of Schal has also been given an advisory role.

Development concepts, construction techniques and management and contracting arrangements are all American inspired. First is the developer’s end product which comes in the form of a bare “shell and core” of a building ready for the tenant to fit out with partitioning, ceilings, raised floors and services geared specifically to its operational requirements, along with desks and furnishings. The shell and core approach avoids the absurd waste of materials, money and time of the tenant ripping out the developer’s fittings to replace them with its own.

Second, construction using at steel frame and composite metal decking allows much speedier dry construction techniques than an in-situ reinforced concrete frame. The system was introduced to London from New York by Stuart Lipton five years ago in his Cutler Street development.

Third, the contractual arrangement at Broadgate, as at London Bridge City, is the American construction management system. It differs from management contracting in that the client plays an integral part in the construction process and indeed holds the contracts with the individual trade contractors. And whereas management contracting can easily get bogged down in paper shuffling, the client in construction management can knock heads together by sitting down at the table with the project’s construction managers, designers and trade contractors and mobilising the spectrum of experience at hand. An expert and committed client’s representative is of course vital to the system.

Not that the Broadgate team waits around for problems to arise. Problems are forestalled by the fourth American technique known as value engineering. As with other novel techniques used at Broadgate, it was developed for another industry, in this case the United States defence industry. “It is a way of assessing the cost and efficiency of each design decision,” says Ian Macpherson. “In a disguised fashion, every good contractor already does this for his own profit, but with the client’s involvement through construction management, it is done for the client’s benefit.”

“There are two key catchwords at Broadgate,” sums up Macpherson. “The first is “why?”, which is what value engineering is about. The second is ‘can do’, which comes with construction management, as distinct from ‘no can do’, which is the usual British approach.”

Specialists on the front line

Trade contractors, who play a critical role in the fast-track process, are closely vetted for their ability to cope. “These are high-risk contracts here,” stresses Macpherson. “If they don’t succeed, the penalties are very high. But we make sure to get the A-team of every contractor.”

The A-team approach starts at the top at Broadgate. Peter Foggo’s team are accepted as the crack troops of Arup Associates, while Macpherson himself admits to having plugged for a contract from Stuart Lipton for five years. He was recently promoted to Bovis main board for his perseverance.

Overseas suppliers

One of the less praiseworthy results of the intense vetting procedure is that some 30% of the building’s components come from abroad. One example is the lifts, the contract for which was awarded to Thyssen of Germany. “We originally went to the British Express firm,” explains Macpherson. “We warned them that this would be a key job, and we even negotiated a higher price than we eventually got from the Germans. But Express wouldn’t accept the conditions and risks of the contract. I even went as high as Lord Weinstock, but with no success.”

The net effect of the dual approach of value engineering and construction management is that the phenomenal speed of construction has largely been achieved through the rationalisation of construction techniques rather than by throwing thousands of men at the site. It is an approach that naturally points to off-site prefabrication. “The worst place to build a building is on site,” quips Macpherson. In fact, shift working was used on site only for special operations such as cutting the steel decking, the noise of which would disturb neighbouring offices, and the installation of large prefabricated components, which could only be transported in through London streets outside office hours.

The cladding panels make up a fascinating case study of the whole Broadgate approach. Arup Associates had designed a quality-specification panel with sealed double-glazing and granite fins externally to give a sense of solidity. The ace German company Gartner, who had supplied both No 1 Finsbury Avenue and Lloyd’s, was appointed as contractor. The value engineering approach led to the creation of a full-scale mock-up of the cladding three storeys in height, from which the design concept and buildability could be assessed. A leading role in the experiment was played by Bovis’ central research and development team, led by Bob White. “It confirmed to us that pre-assembly would be possible,” he recalls. “We proved to ourselves that assembly on site could not meet the deadlines, and anyway there wouldn’t have been the skilled manpower available in Britain.”

The solution that was eventually adopted was to pre-assemble each panel one storey in height (3.2 metres) and 7.5 metres in width, with glazing units, external granite fins and internal heating radiators all intact. These large and delicate panels were then hoisted into position using a specially designed A-framed sky-hook. Value engineering applied to the mock-up also led to the replacement of the original steel structural core of the panels with a more economic aluminium core. The district surveyor and fire officer were kept abreast of design developments, so that statutory approvals caused next to no delay.

The construction team also discussed how such a large quantity of natural stone could be procured and assembled on time. A convoluted solution was eventually arrived at in which Swedish granite was pre-bought and supplied to Italy for working and then shipped to Gartner’s yard in Bristol, where it would be assembled with the aluminium section and glass, both supplied from Germany, along with the British radiators. As well as meeting the all-important deadlines, the value engineering exercise on the panels also produced cost savings. amounting to 10% of the contract, or more than £1 million, Peter Rogers alleges.

Both the structural steelwork and the sprayed fire protection were contracts that benefited from the team approach and study trips to the United States. As a result, steel contractor Redpath Engineering along with its erectors Smallman agreed to lift the steel sections into position three at a time using the chandelier method. In addition, basement walls were inserted after the superstructure had been erected above, while the superstructure itself was put up not conventionally floor by floor but by dividing each building into a dozen or so blocks to be erected in a carefully planned sequence.

As for sprayed fire protection, Bovis proposed that the quickest method would be to spray from a central source rather than laboriously move the batching plant and pump around the building. A visit to the United States followed by tests in England eventually persuaded sceptical British specialists.

Although the design of financial dealing floors had been painstakingly researched before construction began and both phases had been successfully pre-let, these were inevitably changed during construction to suit specific tenants’ requirements. In the event, the tenant of phase 2 decided after construction had begun to fill in the atrium on three floors. However, this was achieved while maintaining the overall construction programme, as foundations and steel columns, beams and bolt holes had been deliberately overdesigned by some 15% in bearing capacity.

Perhaps the most spectacular time-saving devices used at Broadgate were the entire pre-assembly of toilets and air-conditioning units. The concept was borrowed by Bovis from its Lloyd’s site, where the “pods” have been used to much more flamboyant if risky effect on the exterior of the building.

After having been completely fitted out at the trade contractor’s yards, the pods were hoisted into the Broadgate buildings through gaps left in the cladding. They were then floated over the floor into their final positions by a fleet of air-skates or miniature hovercraft used in heavy industry. After that, on-site work on the toilets and air-conditioning units comprised little more than final connections and commissioning.

No cost penalty

What in retrospect have been the extra costs of such frenetic activity at Broadgate? “Negligible,” claims Peter Rogers, “because the client’s involvement in construction management ensures that trade contractors are paid promptly, and this saves them interest payment on outstanding loans.” Bovis’ team of 30 is fewer than would be required in management contracting, adds Ian Macpherson: “We have a small and efficient team here.”

High speed building likewise accomplishes one of developers’ prime goals to reduce the period a site is out of production and bringing in revenue through rents. Total building costs at Broadgate, including standard developers’ fitting out and consultants’ fees, amounts to only about £850/m2, some 20% lower than comparable spec office blocks in central London and less than a third of the cost of the new Lloyd’s building, designed by Peter Rogers’ brother, Richard.

The most off-beat American import at the Broadgate site takes the form of frequent celebrations to maintain team spirit. Despite the American influence underlying the whole project and the European supply of components, the British development team has good cause to celebrate. “The rest of the world could learn a lot from this site,” boasts Macphersone.

More from the archives:

>> Nelson’s Column runs out of money, 1843-44

>> The clearance of London’s worst slum, 1843-46

>> The construction of the Palace of Westminster, 1847

>> Benjamin Disraeli’s proposal to hang architects, 1847

>> The Crystal Palace’s leaking roof, 1851

>> Cleaning up the Great Stink, 1858

>> Setbacks on the world’s first underground railway, 1860

>> The opening of Clifton Suspension Bridge, 1864

>> Replacing Old Smithfield Market, 1864-68

>> Alternative designs for Manchester Town Hall, 1868

>> The construction of the Forth Bridge, 1873-90

>> The demolition of Northumberland House, 1874

>> Dodging falling bricks at the Natural History Museum construction site, 1876

>> An alternative proposal for Tower Bridge, 1878

>> The Tay Bridge disaster, 1879

>> Building in Bombay, 1879 - 1892

>> Cologne Cathedral’s topping out ceremony, 1880

>> Britain’s dim view of the Eiffel Tower, 1886-89

>> First proposals for the Glasgow Subway, 1887

>> The construction of Westminster Cathedral, 1895-1902

>> Westminster’s unbuilt gothic skyscraper 1904

>> The great San Francisco earthquake, 1906

>> The construction of New York’s Woolworth Building, 1911-13

>> The First World War breaks out, 1914

>> The Great War drags on, 1915-16

>> London’s first air raids, 1918

>> The Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building, 1930

>> The Daily Express Building, 1932

>> Outbreak of the Second World War, 1939

>> Britain celebrates victory in Europe, 1945

>> How buildings were affected by the atomic bombs dropped on Japan, 1946

>> Rebuilding the House of Commons chamber, 1945

>> Planning the postwar New Towns, 1945-46

>> The Festival of Britain, 1951

>> The world’s first nuclear power station, 1956-57

>> Building covers the 1964 election

>> Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral, 1967

>> The new London Bridge, 1973

No comments yet