A year after London hosted the 2012 Games, Ike Ijeh looks at how quickly work is progressing to convert the venues for public use

A year ago today the world’s eyes were on London as the 2012 Olympics began and the Queen pirouetted out of a helicopter. One year later the first part of the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park is set to reopen to the public this weekend. The handball arena also reopens today, the first Olympic venue to do so.

The majority of the park however, including showpiece venues such as the velodrome and aquatics centre will not open until next spring. Many people, with good reason, are irked by the almost two-year closure period and predict that the triumphant 2012 spirit and momentum may well have been exhausted by the time the majority of the park has reopened. Nonetheless the park authorities contend that the closure period has been essential to accommodate the major reconstruction works required and that this weekend’s reopening will provide a tempting taster of what is to follow.

No previous Olympics aligned itself to the pursuit of regeneration as wholeheartedly as London 2012. While a year may not be long enough to gauge how successfully these ambitions have been achieved, the reopening of the park does offer an apt opportunity to provide an update on the reconstruction progress of the various venues and gauge how London 2012’s ambitious legacy aspirations are faring so far.

VELODROME

LEGACY FUNCTION Velodrome and velo-park

STATUS Closed

RE-OPENING DATE April 2014

ARCHITECT Hopkins

CONTRACTOR ISG

CONSTRUCTION COST £93m

For many the velodrome was the architectural jewel in the Olympic park. By the time it reopens to the public next spring, its prominence would have been enhanced all the more by the removal of the basketball arena that once stood adjacent to it and the new Lea Valley VeloPark that will have been constructed around it. The VeloPark will include a BMX track, mountain bike trails and a road cycle circuit and replaces the old Eastway Cycling Circuit demolished to make way for the Olympics, a key legacy commitment. Little conversion work is required to the velodrome itself, with its retractable 6,000 seat capacity maintained. Both the velodrome and VeloPark will be owned and managed by Lee Valley Regional Park Authority. Like the Aquatics Centre, they should provide a world class public leisure facility for the local area and beyond that will be a fitting municipal tribute to the first sports building to be nominated for a RIBA Stirling prize.

AQUATICS CENTRE

LEGACY FUNCTION Public swimming pool

STATUS Reconstruction

RE-OPENING DATE April 2014

ARCHITECT Zaha Hadid

CONTRACTOR Balfour Beatty

CONSTRUCTION COST £269m

The aquatics centre’s much derided wings were arguably the most architecturally controversial (and flawed) feature of London 2012. But all the fuss has been forgotten now they have been dismantled and the streamlined, sculpted profile of the venue has been revealed. Hadid’s building has emerged as what she originally intended, a stunning, billowing, wave-like roof seemingly suspended over the space below. The vast sheets of curtain-wall glazing now being constructed in the voids left by the absent stands help reinforce this concept. Throughout the building’s reconstruction, its three pools are being kept filled with water in order to maintain filtration. When it reopens next spring, its capacity will have been reduced from 17,500 to 2,500 and it will have been reconfigured as a public swimming pool. Operator Greenwich Leisure is committed to pegging prices “to the price of a local swim”, currently around £4 per session. The aquatics centre will also continue to provide elite training and competition facilities and will easily become London’s principal swimming venue.

OLYMPIC STADIUM

LEGACY FUNCTION West Ham FC / Multi-purpose venue

STATUS Closed for partial reconstruction,sporadic event reopening

FULL RE-OPENING DATE August 2016

ARCHITECT Populous

CONTRACTOR Sir Robert McAlpine

CONSTRUCTION COST £486m

History has shown that the Olympic stadium is always the single most difficult venue for which to secure a viable permanent legacy and up until very recently, London maintained this calamitous tradition with assiduous resolve. In March it was finally announced that tenancy and not ownership of the Olympic stadium will pass to West Ham FC on a 99-year lease payable at £2m a year. The club will move in at the start of the 2016/17 football season, by which point the stadium will be reduced from an 80,000 to a 54,000 seater venue and will operate as a multi-purpose venue also hosting concerts, rugby and cricket. The retained running track will also preserve its use for athletics.

New retractable seating and hospitality suites will also be installed at the converted venue. The only significant change to its external appearance will be on its roof which will be rebuilt with a translucent, PVC structure to form, at 84m, the largest span tensile roof in the world. Other developments will include the relocation of key back-of-house facilities such as toilets and concessions from the temporary pavilions that line the stadium perimeter to inside the main stadium structure. A new building will also house the ticket office and merchandise store.

But getting here has not been easy and the lamentable eight-year catalogue of indecision and delay that preceded the decision this March outlines the lunacy of designing a venue of this scale without fixing its post-Olympic role well before construction has even begun. Had this happened then conversion design criteria could have been embedded into the stadium’s initial design thereby avoiding the additional £150m now required to convert it for football use, most of which will be public money.

Nevertheless, the Olympic stadium has already proved its worth as a large-scale events venue and will host the Rugby World Cup in 2015 and the World Athletics Championships in 2017.

ETON MANOR

LEGACY FUNCTION Hockey/tennis centre

STATUS Reconstruction

RE-OPENING DATE April 2014

ARCHITECT Stanton Williams

CONTRACTOR CLM

During the 2012 games the Eton Manor site, named after a philanthropic Victorian East End mercy mission by Eton College, was the site of wheelchair tennis and also housed aquatic training pools. It is being converted into the Lee Valley Hockey and Tennis Centre set to open next year. It will have a capacity ranging from 3,000 to 15,000 and will incorporate a 5,000-seater stadium relocated from the dismantled Riverbank Arena on the opposite end of the park. In 2015 it will host the EuroHockey Nations Championships.

OLYMPIC VILLAGE

LEGACY FUNCTION Residential

STATUS Reconstruction

RE-OPENING DATE August 2013

ARCHITECT Various

CONSTRUCTION MANAGER Lend Lease

CONSTRUCTION COST £1.1bn

The accommodation for the 10,500 athletes who took part in London 2012 has been somewhat anaemically rechristened as East Village and will open to its first residents next month. Of the 2,818 homes provided, 1,379 have been sold to Triathlon Homes to provide affordable housing with the remaining 1,439 now privately owned by a Qatari Diar/Delancey joint venture.

The fact that the private homes have only been offered for rent and not sale is significant, the Olympic village will become the UK’s first private sector residential investment fund. Aside from offering a variety of units ranging from one-bed flats to four-bed townhouses, the 27 hectare site will also provide local shops and restaurants, tree-lined boulevards and from September, an 1,800-pupil school in the new AHMM-designed Chobham Academy.

Part of the reconstruction process involved in converting the site from Olympic to residential use included the installation of thousands of kitchens and the retrofitting of undercroft car parks that had been used as medical, administration and laundry areas for the athletes. The Olympic village is arguably the biggest single test of how well London 2012’s regeneration legacy aspirations will perform. However, as it takes cities and neighbourhoods years to evolve the character that eventually defines them, it will be some time yet before we can judge its success or otherwise. For now the omens look promising, although perhaps considering London’s housing shortage not entirely unexpected. By January, 17,000 people had registered their interest.

HANDBALL ARENA

LEGACY FUNCTION Multi-purpose venue

STATUS Re-opened

RE-OPENING DATE July 2013

ARCHITECT Make

CONTRACTOR Buckingham Group

CONSTRUCTION COST £41m

The Copper Box proved to be one of the most popular venues during the 2012 Olympics, hosting rousing crowd entertainment intermissions as well as handball and modern pentathlon heats. Reopening at the end of this month, London’s third largest arena is the only indoor arena remaining on the Olympic

park after the dismantling of the basketball arena.

It will now host a wide range of sporting, performance, community and cultural events and will provide a gym, sports halls and a cafe as well as concert, meeting and exhibition space. Retractable seating will either maintain or reduce its 7,000 seating capacity as necessary. The simple and restrained architecture is indicative of a venue whose pragmatic approach to post-Olympic conversion has made it a model for how best to design Olympic venues.

Unlike the Olympic stadium, the handball arena was designed to be completely flexible right from the start, hence the lack of any significant post-Olympic conversion works, the admirably prudent budget and the fact that it is the first main Olympic venue to fully reopen.

MEDIA CENTRE

LEGACY FUNCTION Business hub/digital quarter/broadcast studios

STATUS Reconstruction

RE-OPENING DATE August 2013

ARCHITECT Allies and Morrison

CONTRACTOR Carillion

CONSTRUCTION COST £355m

The dullest building on the Olympic park is hopefully set to enjoy a more exciting future when BT Sport, the company’s new group of sports channels, starts broadcasting from here next month. The channels will operate from the new iCity complex, a 900,000ft² “digital quarter” providing commercial accommodation for digital and creative industries and designed to capitalise on east London’s established reputation as a hub of creative enterprise. Loughborough University, Hackney Community College and a data centre operator will also rent space within the complex. The site will cost £100m to convert and the operators have promised to deliver 4,500 jobs.

ORBIT

LEGACY FUNCTION Sculpture/observation tower

STATUS Closed

RE-OPENING DATE April 2014

DESIGNER Anish Kapoor

CONTRACTOR Sir Robert McAlpine

CONSTRUCTION COST £22m

Anish Kapoor’s cyclopean corkscrew certainly enjoyed its share of controversy when its design was first revealed in 2011. But it proved to be a hugely popular attraction to the millions of visitors to the Olympic park last year. It will continue its role as a public observation gallery when it reopens next spring. By then it will also form one of the key landmarks of South Plaza, the recreational epicentre of the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park. It will still charge the public for entry, although officials have intimated that this might be less than the £15 charged to Olympic ticketholders last year. No reconstruction work is required at the Orbit, the only reason it is currently inaccessible is because the southern half of the Olympic park, in which it is located, is shut. When it re-opens, it is hoped that the Orbit will provide an artistic legacy for London 2012 and that it will increase the tourism appeal of the new park.

REGENERATION

On one level, it might be possible to argue that the Olympics have not changed much for the local area. Newham, the principal host borough, is still London’s poorest. Also, despite construction of Westfield and the Olympic park, it still maintains London’s highest unemployment rate and despite the thousands of new homes in the Olympic village it still administers the capital’s longest social housing waiting list, around 70,000.

Some point to key decisions taken during the Olympic construction period as actually aggravating Newham’s problems, namely the government’s move from 100% affordable housing at the Olympic village to 50% (only 350 out of its 2,818 homes will go to Newham council) and Westfield’s commitment to employ only 10% of its construction workforce from the local area. Even worse many, including local Hackney North MP Diane Abbott, allege that of the 44,000 construction jobs available during construction of the Olympic park, less than 10% were allocated to the local workforce.

But disheartening as these statistics may sound, they do not tell the whole story. The physical and economic transformation of the Olympic park and its environs has been astonishing. Eight years ago when London won its bid most of what is now the Olympic park was a derelict and abandoned post-industrial wasteland. Today, Europe’s largest urban park for 150 years is surrounded by scores of housing and commercial developments and the area’s built environment, civic profile and economic confidence have been rejuvenated. Construction has begun on some of the 11,000 further homes planned for the area over the next 20 years and building work is also well under way at The International Quarter (see image, left), a £2bn scheme to create 4 million ft² of offices, 52,000ft² of retail and 25,000 jobs beside Westfield Stratford City.

There can be no doubt that Stratford is a better place after 2012. Gentrification may be creeping in and few of the developments already built, particularly along Stratford High Street, exhibit anything approaching genuinely exciting architecture. But a momentum has been established and a vision defined. It will take time but it is from these seeds that regeneration, eventually, grows.

OLYMPIC PARK

LEGACY FUNCTION Public park

STATUS Partial re-opening

RE-OPENING DATE April 2014

CONCEPT DESIGN EDAW, Buro Happold, Arup, WS Atkins, LDA Design/Hargreaves Associates

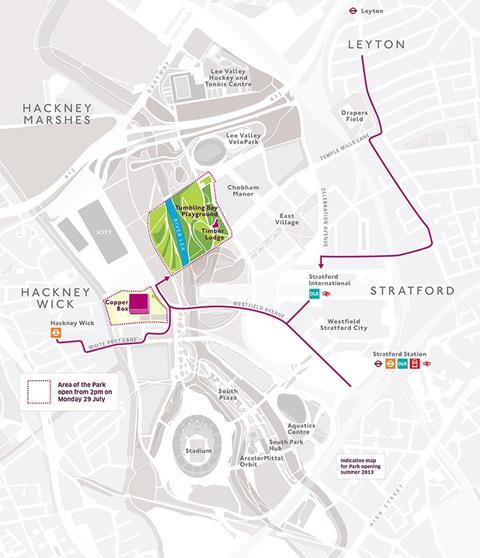

At 2.5km² the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park is the biggest physical legacy of the 2012 games. Larger than Regent’s and Greenwich Parks combined and bigger than Monaco, its enormous size indicates the scale of regeneration ambitions at London 2012. Namely, that the Olympics were not merely about providing a handful of sporting venues but about reshaping a part of the city and bequeathing it a new urban quarter. With 8km of waterway and 4,000 new trees, the park also provides east London with a rich new natural landscape in an area that once scarred by contaminated rivers and disused factories. The park is reopening in two stages. Part of the northern area of the park around the Velodrome opens this weekend with the remainder re-opening next spring.

The northern part of the park has been designed with an organic, naturalistic character and has rolling verges and wildflower embankments akin to a typical English rural landscape. In keeping with its showpiece attractions like the stadium, aquatics centre and Orbit, the southern part will adopt a more urban character with fountains, promenades and a 28-acre plaza.

TRANSPORT

If there is one area where the Olympics can irrefutably claim to have benefited the local area already it is public transport. Not only did the apocalyptic predictions of transport meltdown fail to materialise last summer but various upgrades before and after the Olympics now mean that the Olympic stadium is arguably the most accessible major stadium on earth. Stratford is served by dozens of bus routes and up to eight rail and tube lines including the seven minute “Javelin” service to St. Pancras, the UK’s fastest commuter railway.

There is still more to come. Crossrail will serve Stratford from 2017 and Deutcshe Bahn is involved in albeit protracted channel tunnel license negotiations to break Eurostar’s 19-year monopoly on rail travel to Europe and run services to Frankfurt from Stratford International. Of course the Olympics can’t take all the credit and many of these services, such as High Speed 1, were planned long before London won its bid. But Stratford’s stellar public transport infrastructure already provides the perfect conditions to fuel further post-Olympic regeneration.

Furthermore, it is truly ironic that the one area consistently identified by many as a significant flaw in the 2012 proposals may soon leave Stratford as one of Europe’s key international transport interchanges.

GONE BUT NOT FORGOTTEN

Basketball arena

With a seating capacity of 10,500, Wilkinson Eyre’s rippled marquee was the largest ever temporary indoor arena constructed in Olympic history. The 12,000 capacity arena’s fame was considerably heightened by widely publicised plans to dismantle it after the Games and transport it to Rio to act as the basketball arena for the 2016, a venture that was sadly abandoned shortly before the games began. Instead it has now been dismantled and is on sale for £2.5m for relocation and reassembly at an alternative site. The sale involves the shell alone: 3,000 seats will be incorporated into the new Lee Valley Hockey and Tennis Centre, 7,000 have already been sold and the remaining 2,000 will be leased for rent. The basketball arena site will soon be the location of Chobham Manor, a development of 850 homes.

Water polo arena

The water polo arena’s mono-pitch profile was one of the first sights to greet visitors to the Olympic park last year. Its lightweight construction was similar to that of the basketball arena - high-tension PVC cladding stretched over a skeletal steel frame. When dismantled, most of its materials were recycled or, due to the quantity of temporary construction industry components used, fed back into the supply chain.

Riverbank arena

See Eton Manor box above.

3 Readers' comments