Efficiency has long eluded the construction industry - but now the government is demanding cuts in costs of up to 20%. So any company wanting public sector work had better think up some pretty clever ways to help make that happen

When George Osborne sat back down after delivering his Budget speech to roars of approval from his own benches last week, the industry may have momentarily relaxed. No new surprise cuts, and a decent package for businesses. Yet buried in the Treasury’s Plan for Growth that accompanied the chancellor’s speech was the mother of all challenges for the industry: reduce costs by up to 20%.

The government envisages a three-pronged attack. It is going to “encourage standardisation rather than bespoke designs,” set “clear criteria for asset performance” and bring in “new models of procurement”. The Cabinet Office has clarified that it is looking to save “10-20% over the next four years” but will only reveal exact details in May. Most in the industry think the savings are possible. Yet how can construction shave a fifth off its costs when the Latham and Egan reports in the nineties seemed to bounce off an entrenched industry?

Although few complained at the time, the Building Schools for the Future programme is now seen as the most extravagant example of the “bespoke” design the government wants to squeeze. David Mathieson, head of public sector at Turner & Townsend, says savings of 20% can easily be made by passing design from architects to contractors. “A bespoke school might come in at £2,500/m2, but a contractor-designed one can be done for £1,700-£1,800/m2,” he says.

Standardisation of hospitals is perfectly possible too, says Christopher Shaw, director of MAAP architects. “Standardisation is something that has sat behind hospital design for as long as I have been involved with it,” he says. They were made more uniform after the oil crisis in the seventies, he adds, and have become even more so since. Compared with the French, for example, Shaw thinks British hospitals are 20-30% more expensive. “We do things expensively on the engineering side,” he says.

Yet this is largely down to a “gold plating” of specifications like fire safety, which risk-adverse NHS managers will be loath to discard, rather than “bespoke” design, Shaw believes. And without a big drive of work, it will be impossible to get the large contractors to standardise public buildings like hospitals for production off site. “You want to go to Laing O’Rourke or Balfour Beatty and have systems, but we don’t have the demand or appetite for large hospitals of that type.” In other words, a public sector recession is the worst possible time to try to standardise.

“Flat pack” public buildings could also run into problems from a generation of architects determined to make their mark with a signature project. “We don’t want to work with architects who are trying to build the new Stirling Prize,” says Chris Gilmour, director of design and marketing at BAM. He thinks standardisation will squeeze them, but most are determined to work within a budget. “Most architects try extremely hard to standardise,” says Shaw. “It needs to be driven by architects not contractors.”

Architects argue that not only are they open to standardisation but that they are crucial to cutting costs through good design. “You do not throw out the architect to save money,” says Angela Brady, RIBA president-elect. “If they [the government] ask us, we can tell them about new ways of working that can save money and time and that good design in itself does not cost money but can enhance all aspects of our built environment,” she says.

Standardisation could also constrict the localism agenda. “Headmasters may get to choose their own design [of school] but from a limited pattern book,” says Stephen Ratcliffe, director of the UK Contractors Group. “It doesn’t feel like it’s gelling together.”

The second weapon in the government’s armoury is better procurement. Few doubt savings can be made here, and this emphasis is hardly a surprise. The Plan for Growth argues that “fragmentation of the public sector client base” drags down public sector efficiency, as do “inconsistent procurement practices”. Some expect that fewer, bigger frameworks are the answer to this problem, yet this clashes with the parallel aim of bringing in more SMEs to the public sector table. “From the SME side, bigger frameworks would be counter to what the government has been saying,” says Alasdair Reisner, head of public affairs at the Civil Engineering Contractors Association.

The third - and most nebulous - idea the government has floated is “setting clear criteria for asset performance”. Chief construction adviser Paul Morrell says he understands it means looking at “whole life value based on a clear stated understanding of the outcome the asset is intended for,” presumably instead of detailed design specifications. Morrell, who will be leading the cost-cutting drive, has put forward the idea of getting contractors to run public sector buildings for five years after construction to force them to think harder about how they will operate. But there could be a contradiction between spending less on buildings and pressing for them to be cheaper to run while operating. “There’s a tension between capital and revenue spend,” says Shaw. “You can make the savings in capital, but it might lead to a higher revenue outlay.”

Still, everyone thinks the 20% figure is possible - partly because the announcement is not seen as a smash and grab raid on contractors’ profits, but a call to work more cleverly. “If the government was going to cut costs out of contractors’ margins there would be a cause for concern,” says Ratcliffe.

But if cutting 20% from the cost of construction is so doable, then why has it not happened before? “That’s an extremely good question,” says Mathieson. “I think the government is saying it’s got to work or we will start looking at margins.” The industry has told the government it is wasteful and can do better, and so has been spared the immediate price cuts cabinet office minister Francis Maude has eked out of other suppliers. The pressure is on to deliver.

The education test

The first sector to feel its way into the new era of standardised design will be education. The long-awaited review into the future of the government’s school building programme, led by Sebastian James, could be published as soon as next week - and standardisation is expected to be a core focus.

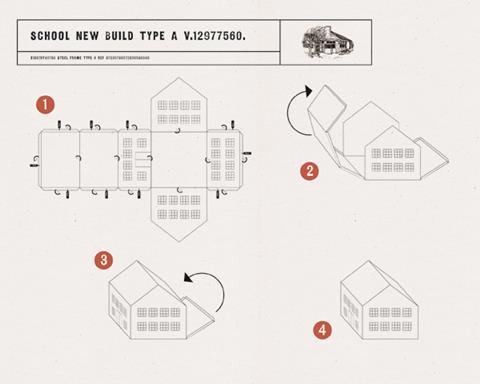

The review team believes that not just component parts but whole classrooms and even entire schools can be built to standardised designs. Several contractors and architects have already started working up buildings aligned to this agenda - such as the Sunesis suite of pre-designed, off the shelf schools developed by Willmott Dixon in partnership with local government procurement organisation Scape and architects including White Design and Atkins (pictured above). The designs are claimed to save 20% off the cost of an equivalent bespoke school, and with only a third of that reduction due to a standardised build process, those involved believe that with future supply chain innovations the saving could be as much as 30%.

Once the review, which was commissioned when the government scrapped the £55bn Building Schools for the Future programme last summer, is published, and the specifications the government is looking for are clearer, more will follow. However, detailed work on new space standards - which could be reduced by as much as 15% - is not expected to be published until after the review, which threatens to hold up progress with new designs.

No comments yet