Ike Ijeh reviews this year’s Serpentine Pavilion, which opens to the public on Thursday

Construction of the 15th annual Serpentine Pavilion, designed by Spanish practice SegasCano and engineered by Aecom, has been completed.

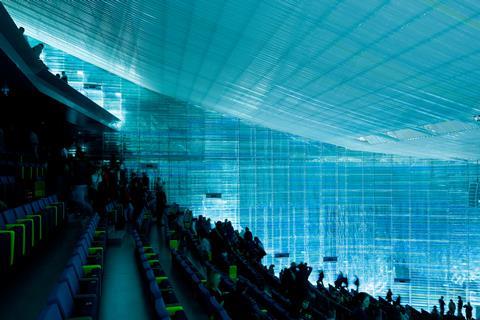

The kaleidoscopic temporary exhibition space, built out of multi-coloured EFTE panels woven through a steel frame, opens to the public on Thursday and will close on 18 October.

It is expected to be visited by around 200,000 people. Previous pavilions have been designed by Frank Gehry, Rem Koolhaas, Zaha Hadid and Oscar Niemeyer.

Tom Webster, UK associate director at Aecom, said: “As engineers, the key to delivering a successful pavilion is to transform the architect’s vision into a functional space for people to enjoy.

“In just seven weeks, the team has constructed a unique visitor experience that is structurally stable, yet maintains selgascano’s original vision.”

‘A labyrinthine translucent whorl’: Architecture critic Ike Ijeh’s verdict

Transport for London appears to be an unwitting muse for an increasing number of Serpentine Pavilions. Five years ago Jean Nouvel drenched his in a decadent blood red hue as a ripe cinematic homage to the London Bus. And for this year’s offering we have colourful Spanish duo SelgasCano creating a labyrinthine translucent whorl partially inspired by the convoluted connectivity of the London Underground.

Like all Serpentine Pavilions, this one is a work of decadent, avant-garde and decidedly esoteric architecture. A series of polygonal, amorphous tent-like structures is constructed to incorporate a series of circuitous perimeter routes, referred to by the architects as “secret corridors” that lead to a central, womb-like void. The structure is shrouded in ETFE psychedelically tinted in various shades, rather like a three-dimensional version of the polychromatic streaks that sometimes cling to the edges of rainwater puddles, another unwittingly apt reference, perhaps, to London’s climate.

Occasionally, strips of brightly coloured banding are attached to the inner or outer face of the ETFE to provide a more diffuse envelope. The inner room itself is conceived as a sanctuary with the architects alluding to the “stained glass” effect created by the coloured ETFE and which both frames and subtly distorts views out to the park landscape.

The architects talk passionately about the themes that charged their work, their desire to create a spatial and visual experience actively manipulated by considerations of light, transparency, colour and surprise. In that sense it works. It is certainly colourful and bright and has an engaging Pop Art irreverence that is more visually engaging that last year’s curious prehistoric cave. Moreover its complex footprint and convoluted layout make for an intriguing piece of architecture that invites discovery and exploration, even if the “secret corridor” analogy is seriously compromised by a transparent multi-coloured skin.

But, unexpectedly, the Tube reference is what compels the most. The best Serpentine Pavilions always reference context and the city in order to anchor themselves to their surroundings. This is why Peter Zumthor’s walled garden of 2011, a dark monastic inversion of Hyde Park’s rolling landscape, remains one of the most memorable recent offerings. Equally, references to red buses and convoluted underground networks may seem trite and hubristic but they provide an important architectural prism which reflects an image of how foreign architects perceive London.

Some of the best pieces of art are created by those working in an adopted foreign environment. While familiarity inevitably breeds inhibition, those unaccustomed to our customs and conventions can cast a culturally unconditioned eye over what we take for granted. Alfred Hitchcock may have been a prim Englishman from Leytonstone but his spellbinding cinematic evocation of the vast landscapes and urban menace of America still stand as some of the most viscerally compelling depictions of that country ever committed to screen.

So it is with this year’s Serpentine Pavilion. Like all Serpentine Pavilions it may be frivolous and rarefied but this one’s also bright and colourful and children will love it. But what makes it and every other Serpentine Pavilion really interesting is not what we see in it but what it tells us about how others see us.

No comments yet