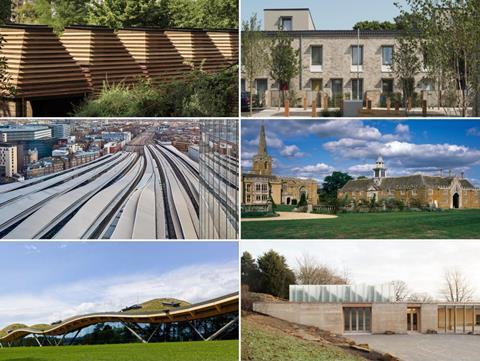

London Bridge station redevelopment and Macallan Distillery among beaten schemes

Mikhail Riches and Cathy Hawley have won the 2019 Stirling Prize for Goldsmith Street, a highly sustainable council housing development in Norwich.

It is only the second time in the prize’s 23-year history that housing has won. The last time was in 2007, when Accordia, the Cambridge scheme designed by Feilden Clegg Bradley Studios, Alison Brooks Architects and Maccreanor Lavington, lifted the trophy.

Costing £14.7m, Goldsmith Street was completed by local contractor RG Carter last December with others to work on the job including QS Hamson Barron Smith, clerk of works Enhabit and landscape architect BBUK.

Julia Barfield, chairman of this year’s jury, described Goldsmith Street as a “modest masterpiece” and an outstanding contribution to British architecture.

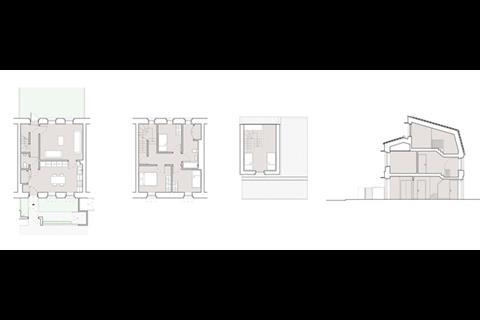

Consisting of nearly 100 houses and flats laid out in traditional terraced streets, the project meets rigorous Passivhaus standards, resulting in annual energy bills that are 70% lower than the average household’s.

RIBA president Alan Jones, another of the judges, said: “Faced with a global climate emergency, the worst housing crisis for generations and crippling local authority cuts, Goldsmith Street is a beacon of hope.

“It is commended not just as a transformative social housing scheme and eco-development, but a pioneering exemplar for other local authorities to follow.”

The project also picked up the RIBA’s inaugural Neave Brown Award for Housing at tonight’s ceremony at Camden’s Roundhouse.

It was commissioned by the council more than 10 years ago. A delighted David Mikhail of Mikhail Riches said: “Goldsmith Street’s success is testimony to the vision and leadership of Norwich City Council. We thank them for their commitment and support. They believe that council housing tenants deserve great design.

“It is not often we are appointed to work on a project so closely aligned with what we believe matters; buildings people love which are low impact. We hope other Local Authorities will be inspired to deliver beautiful homes for people who need them the most, and at an affordable price.

“To all the residents – thank you for sharing your enthusiasm, and your homes, with everyone who has visited.”

Julia Barfield, chair of the jury and co-founder of Marks Barfield

Goldsmith Street is a modest masterpiece. It is high-quality architecture in its purest, most environmentally and socially conscious form. Behind restrained creamy façades are impeccably detailed, highly sustainable homes – an incredible achievement for a development of this scale.

This is proper social housing, over 10 years in the making, delivered by an ambitious and thoughtful council. These desirable, spacious, low-energy properties should be the norm for all council housing.

Over a quarter of the site is communal space – evidence of the generosity of the scheme. A secure alleyway connects neighbours at the bottom of their garden fences and a lushly planted communal area runs through the estate, providing an inviting place for residents to gather and children to play, fostering strong community engagement and social cohesion.

Goldsmith Street is a ground-breaking project and an outstanding contribution to British architecture.

Goldsmith Street’s success put paid to Rogers Stirk Harbour & Partners’ hopes that, with its shortlisted Macallan Distillery in Scotland, it would match Fosters’ record-setting three Stirling wins.

The other finalists were Grimshaw’s London Bridge Station, Witherford Watson Mann’s Nevill Holt Opera in Leicestershire, The Weston at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park by Feilden Fowles, and the Cork House in Berkshire by Matthew Barnett Howland with Dido Milne and Oliver Wilton. The latter picked up the Stephen Lawrence Prize, while Grimshaw’s client, Network Rail, was named client of the year.

Councillor Gail Harris, Norwich’s cabinet member for social housing, said it was an “incredibly proud moment” for the city.

“Winning this prestigious award shows that it is possible to build fantastic new council homes, despite the challenges posed by central government cuts and restrictions around Right to Buy receipts,” she added.

The homes are designed around a grid of streets and car-free ginnels. The palette of materials references Norwich’s history, with the glossy black roof pantiles a nod to the city’s Dutch trading links and the creamy clay bricks similar to Victorian terraces nearby.

To ensure the windows echoed Victorian proportions but also met Passivhaus requirements, the architects developed a recessed feature, giving the impression of a much larger opening but limiting the amount of glass. Bespoke steel mesh garden gates and brightly coloured front doors are intended to give each home a strong sense of individuality and ownership.

The jury for the 2019 RIBA Stirling Prize was: Julia Barfield (chair); RIBA president, Alan Jones; last year’s winner, Michael Jones of Foster & Partners; lay assessor and heritage specialist Kathy Gee; and Zac Monro, principal at Zac Monro Architects. Architect Gary Clark was sustainability advisor.

Ike Ijeh on the 2019 Stirling Prize shortlist

No one can doubt that Goldsmith Street is an accomplished work of architecture that has set a new benchmark for sustainability.

The 100-unit social housing scheme is the UK’s largest Passivhaus development.

In design terms too Goldsmith Street has unquestionable merit. Inspired by the tradition of Victorian terraced housing in adjacent conservation areas, the scheme is based on the concept of streets as much as it is on buildings.

Goldsmith Street therefore does all the right things and ticks all the right boxes in today’s febrile political arena.

But life should be about inspiration as well as instruction and for all its dutiful worthiness, Goldsmith Street lacks that special spark and magic that separates good architecture from great architecture.

The building which, in my own opinion, was most deserving of this year’s Stirling Prize was Grimshaw’s heroic overhaul of London Bridge Station from dingy subterranean rat-run to a soaring, light-filled, cathedral-like vault.

But it was not to be. Which begs the question, why did Goldsmith Street win? Could it perhaps have anything to do with the fact that sustainability is the zeitgeist of the moment and its victory is as much to do with messaging as with merit? All credit to Goldsmith Street for its win. But no issue – not even sustainably – is above intellectual debate and architecture, of all disciplines, should be about the interrogation not indoctrination of ideas.

Ike Ijeh is Building’s architecture critic

No comments yet