Ecobuild brings a flavour of Morocco (via the West Country) with mud houses

While many people turned up to Ecobuild looking for new technology, some very old build practices attracted quite a crowd.

Drawn, perhaps, by the smell of freshly cut green oak, a bevy of people, always slow moving and curious, hovered around the Defra-sponsored natural-materials stand.

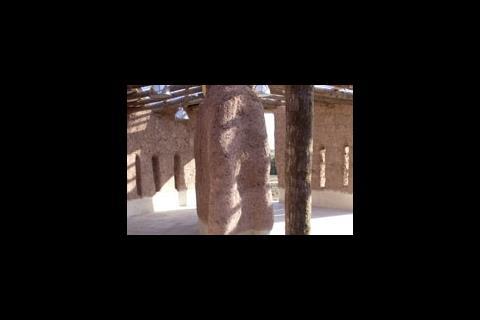

There, carpenters Jasper Emanuel and Joel Hendry and earth architects and builders, Jill Smallcombe and Jackie Abey showed off natural building methods.

People marvelled at the shine on the linseed-oiled, beeswaxed, interlocking earth tiles and the variety of colours and textures and at the sheer weight of the earth and straw mix (cob) blocks.

Discussions were to be heard about Hendry’s fantastic, deep-pocketed German carpenters trousers and a couple engaged Emanuel in an earnest discussion about building one of his timber frame constructions for a conference stand in the future. It may have been a demo, but the mud on Abey’s boots was and the sweat on Emanuel’s brow was real enough.

Making cob buildings

Building a cob structure in the Abey Smallcombe manner seemed simple enough. You mix together your earth and straw and then you jump up and down on it (or drive a tractor over it) to get all the water out.

Emanuel said: "There are a lot of shiny things around here. But they can’t see the inside of the technology. They come here to see bits of wood flying. They love it."

He and Hendry are using hand tools where they would normally use power tools in the workshop. They shape their green oak pegs (green oak is softer, living wood is up to 45% water) on a wooden handmade shaving or draw horse, with a foot-operated clamp. Long, thin, oblong blocks are gradually rounded by shaving ever-thinner corners away, creating a round peg. Like the cob making, it looks simple. Making the massive timber joists with a mallet and chisel looks a bit trickier, I grant you, but nothing you can’t do with a bit of practice.

It’s easy to confuse simplicity with easiness; it’s a fair bet that few attendees, appetites whetted, would be able to create a timber frame of the elegance of that on the stand.

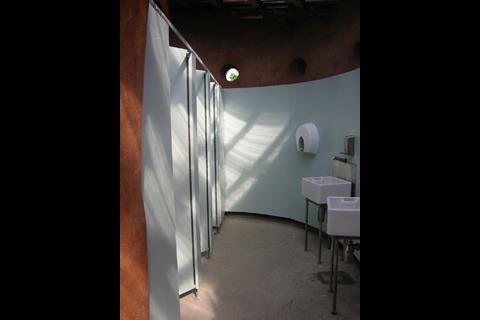

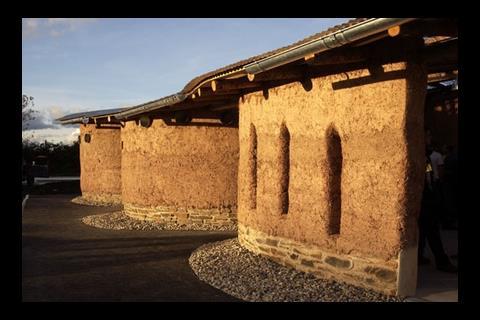

And Abey Smallcombe’s shelters, stands and sculptures have a beauty all of their own, especially the gothic arched seat with limestone was. They were both artists first of all, after all even if the pair have carried out construction projects for organisations, such as Sustrans and the Eden Project.

People come over here to see some wood fly

Trouble with mud

But what if it rains on your mud house? Abey points out that her cob house in Drewsteignton, near Exeter, is over 500 years old. There are over 400,000 cob buildings in the South West of England and over a third of the world’s population lives in earth buildings. It doesn’t take a minute to figure that the material’s sustainability credentials are second to none. It’s natural and sun dried and abundantly available.

Recyclability? The joy of it is if you don’t like what you’ve done, you just knock it down, Abey says. Snagging? If you forget to put a window in where you’d meant to, you just knock it through with a sledgehammer.

In terms of social sustainability, creation of both timber and cob houses used to be a community event, probably by necessity. It took a village to jump up and down on cob to squeeze the water out and the timber frames needed many men to hoist them into the vertical.

But just because the technology is old doesn’t mean there aren’t advances to be made. Although oak is being worked on the stand, Emanuel is keen to extol the virtues of Douglas fir. It’s lighter than oak for one thing, he says, and it’s grown and well-managed in the UK, particularly the West country. What’s more, it’s half the price of oak. Abey and Smallcombe’s experimentation with tints and shape keep their technology moving forward.

One consequence of the sustainable construction revolution, promised or actual, is that traditional materials such as these as well as straw bale building and wool insulation moving back into the mainstream. Earl’s Court Arena, spiritual home of the Ideal Home Show, might just be the place for that.

Surviving material

Phil Woolas, environment minister, said he thought that brick and concrete would be a “thing of the past” in twenty or thirty years. He gave a thumbs up to hemp (while saying he had to be careful about how he phrased this.)

Natural materials, of course, are a product of agriculture and the Minister was no doubt thinking of increased local crop yields with glee. He may get his way. An by-product of forestry are wood pellets which can be used for biomass boilers. These are the most commonly specified renewable energy element in new schemes, according to the GLA’s climate impact head, Andy Deacon. UK tree cover has increased from 5-10% since 2000.

No comments yet