Building covers the opening of Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano’s revolutionary Paris art centre, the first major example of an ‘inside-out’ building

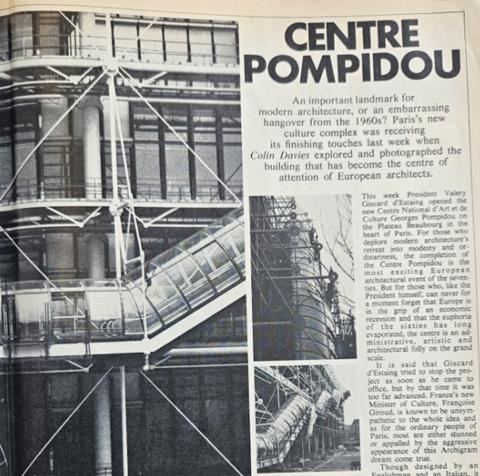

Arguably the most famous building of the late 20th century, the Pompidou Centre marked a turning point in modernist architecture. Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano’s colourful and iconoclastic creation, completed in 1977, was a shocking departure from the austere brutalism of the 1960s and 1970s. In place of concrete and minimalist flat walls, it was covered in a dense network of brightly painted ducts and pipes.

One of the first and still the defining example of an ’inside-out building’, its services had all been moved outside to allow its internal spaces to be free from columns and structural interruptions. This meant that the centre could be easily adapted, allowing novel interactions between the various arrt forms it was designed to house.

The building is still striking today, but, as is made clear in the article below, it is more surprising that it ever got the green light in the first place in a city which has notoriously strict planning rules. Building’s coverage of the opening of the building describes it as the “most exciting European architectural event of the seventies”.

Feature in Building, 4 February 1977

This week President Valery Giscard d’Estaing opened the new Centre National d’Art et de Culture Georges Pompidou on the Plateau Beaubourg in the heart of Paris. For those who deplore modern architecture’s retreat into modesty and ordinariness, the completion of the Centre Pompidou is the most exciting European architectural event of the seventies. But for those who, like the President himself, can never for a moment forget that Europe is in the grip of an economic recession and that the euphoria of the sixties has long evaporated, the centre is an administrative, artistic and architectural folly on the grand scale.

It is said that Giscard d’Estaing tried to stop the project as soon as he came to office, but by that time it was too far advanced. France’s new Minister of Culture, Françoise Giroud, is known to be unsympathetic to the whole idea and as for the ordinary people of Paris, most are either stunned or appalled by the aggressive appearance of this Archigramn dream come true.

Though designed by an Englishman and an Italian, it is in many ways a typically French building. It is as completely uncompromising as the Eiffel Tower, or

Haussmann’s boulevards, or that other monument to Pompidorian wealth and confidence, the Tour Montparnasse. Its basic programme, to bring together all the forms of art under one roof in the centre of the capital city, is typical of French centralist thinking.

Pompidou’s original conception was of a powerhouse of the arts which would put Paris back on the cultural map and would become the centre of gravity of all that was new on the European arts scene. The building was to house a library, an industrial design centre and a gallery for the plastic arts as well as space for performances, whether theatrical, musical or cinematic. But most important of all it was to provide the means whereby the various art forms could come together to generate new ideas and the general public could become involved in the creative process.

The form of the building was obviously going to be very important for the achievement of these aims. An international competition was therefore launched to choose the architects and from a total of 681 entries the jury, chaired by Jean Prouvé and including such architectural big names as Philip Johnson and Oscar Niemeyer, chose a scheme designed by Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano.

Flexibility first

The design has changed considerably since July 1971 but the principles have remained constant. Flexibility has been the number one priority throughout. The building is a stack of enormous rectangular floors, sometimes as big as two football pitches, which are completely free from columns, permanent partitions, or interruptions of any kind.

These spaces are covered by a comprehensive and accessible services grid so that in theory anything can take place anywhere. In order to achieve this ideal, lifts, staircases, escalators, vertical air conditioning ducts, drains, water pipes and electrical cables have been attached to the outside of the building.

The programme for the centre - to bring together the different art forms in multifarious combinations - has prompted the architects to strive almost obsessively for a particular kind of flexibility. But in achieving this flexibility they have also given themselves the opportunity to indulge a taste for the sculptural forms and glossy, rounded surfaces of pipes and ducts. Rather than hide them away, Piano and Rogers have painted them in bright colours (blue for air conditioning, green for water, yellow for electricity, etc) and let them take over the whole of the façade facing the Rue du Renard. Even the escalators, which snake their way up the opposite side of the building facing the Place Beaubourg, are sheathed in a round transparent duct.

The other essential for the achievement of the all-important flexibility is a long span structure. The tubular steel trusses which support each floor are 48 m long. They rest in steel brackets hinged on circular section steel columns. To counter-balance the enormous weight of the trusses (manufactured by Krupp of West Germany) the brackets are anchored by tension rods to the ground. The whole assembly is given longitudinal stability by diagonal cross bracing linking the ends of the brackets.

Following the ruthless logic of functional expression, all the components of the steel frame are exposed and painted white for emphasis, even though this involves the installation of a complicated water cooling system to satisfy the fire regulations.

So much for the structure and the services, designed in consultation with Ove Arup and Partners. But what of the walls? Hidden as they are behind the paraphernalia of clip-on pipes and escalators, they are perhaps the least important visual element. They consist simply of regular lightweight panels, mostly of glass. But even here the opportunity is not missed to express the structural function of the mullions, which are designed as small vertical steel trusses.

Having created the ultimate in flexible interior space, Piano and Rogers have gone one step further and allowed the activities of the centre to spill out onto the adjacent square. The building occupies only half of the Plateau Beaubourg site. The other half becomes what Richard Rogers has described as “a multi-purpose, public participation, entertainment, information area”.

The square will be an extension of the building, accommodating all the events which might suffer from being contained in a building, however open and flexible. Video screens displaying news, film shows, visual games and the like will be clipped on to the building facing the square. Television, video and film will be used both for happenings at the centre and for broadcasts to the rest of France and abroad.

The main contractor for the building was Grands Travaux de Marseille.

It comes as a small disappointment to find that the various components of the art amalgam - the Museum of Modern Art, the Industrial Design Centre, the Public Information Library and the Institute of Research and Coordination Acoustical Music (IRCAM) - have already been assigned to specific areas of the building. Of course, in theory, the boundaries are purely notional, but one wonders whether they may not too easily become jealously defended kingdoms.

IRCAM, under its director Pierre Boulez, is to be housed in a separate underground building between the main centre and the Eglise St Merri. The central space is a hall, with room for 400 people, known as the “espace de projection”. This will be used for experiments into acoustic conditions and the relationship between listeners and sound sources, whether live or recorded. The space can be completely transformed, both visually and acoustically. The height of the ceiling can be varied from nine to 14m and reverberation times can be changed by adjusting rotating panels with absorbant or reflective surfaces.

Final distillation

Architecturally, the Centre Pompidou is the last distillation of a set of visual and conceptual ideas which, though they have been an element of Modern Movement thinking since the twenties, really began to gain currency in the late fifties and early sixties. The idea of a comprehensive services grid which can be “plugged into” at any point has its echoes on the large scale in Yona Friedman’s “Spatial City” of 1961 and Peter Cook’s “Plug in City” of 1965 and, on a smaller scale, in the underground Monte Carlo Entertainments Building designed - and very nearly built - by Archigram in 1969.

The preoccupation with the visual potential of pipes and tubes can be traced back to the “bowellist” schemes of Michael Webb in the late fifties, while the external cross-braced steel frame was foreshadowed, in a much smaller and simpler form, in the factory at Swindon which Richard Rogers designed in partnership with Norman Foster.

But, with the exception of the factory, these were unbuilt projects. The ideas have now become startling reality.

More from the archives:

>> Nelson’s Column runs out of money, 1843-44

>> The clearance of London’s worst slum, 1843-46

>> The construction of the Palace of Westminster, 1847

>> Benjamin Disraeli’s proposal to hang architects, 1847

>> The Crystal Palace’s leaking roof, 1851

>> Cleaning up the Great Stink, 1858

>> Setbacks on the world’s first underground railway, 1860

>> The opening of Clifton Suspension Bridge, 1864

>> Replacing Old Smithfield Market, 1864-68

>> Alternative designs for Manchester Town Hall, 1868

>> The construction of the Forth Bridge, 1873-90

>> The demolition of Northumberland House, 1874

>> Dodging falling bricks at the Natural History Museum construction site, 1876

>> An alternative proposal for Tower Bridge, 1878

>> The Tay Bridge disaster, 1879

>> Building in Bombay, 1879 - 1892

>> Cologne Cathedral’s topping out ceremony, 1880

>> Britain’s dim view of the Eiffel Tower, 1886-89

>> First proposals for the Glasgow Subway, 1887

>> The construction of Westminster Cathedral, 1895-1902

>> Westminster’s unbuilt gothic skyscraper 1904

>> The great San Francisco earthquake, 1906

>> The construction of New York’s Woolworth Building, 1911-13

>> The First World War breaks out, 1914

>> The Great War drags on, 1915-16

>> London’s first air raids, 1918

>> The Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building, 1930

>> The Daily Express Building, 1932

>> Outbreak of the Second World War, 1939

>> Britain celebrates victory in Europe, 1945

>> How buildings were affected by the atomic bombs dropped on Japan, 1946

>> Rebuilding the House of Commons chamber, 1945

>> Planning the postwar New Towns, 1945-46

>> The Festival of Britain, 1951

>> The world’s first nuclear power station, 1956-57

>> Building covers the 1964 election

>> Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral, 1967

No comments yet