The Builder reports as London is assaulted by nightly German bombing raids

Britain was in dire straights during the autumn of 1940. After the fall of France to Nazi forces, but before Russia and the United States had formally entered the war against Germany, it was the only major power still standing against Hitler.

Following the Battle of Britain, which raged above southern England during the summer, the German leader switched tactics and turned to indiscriminate bombing of London in an effort to break morale.

If the pages of the Builder in late 1940 and early 1941 are anything to go by, Hitler appears to have been unsuccessful in his aim. Editorials during The Blitz, which lasted from September to May, focused just as much on how the capital would be rebuilt after the war as they did on the extent to which it was being destroyed in Germany’s nightly bombing raids.

“That we should even be thinking of the making good of war damage while still preoccupied with war-making may be taken as a symbol of our unbounded confidence in the final result,” was the opening line of one editorial in November.

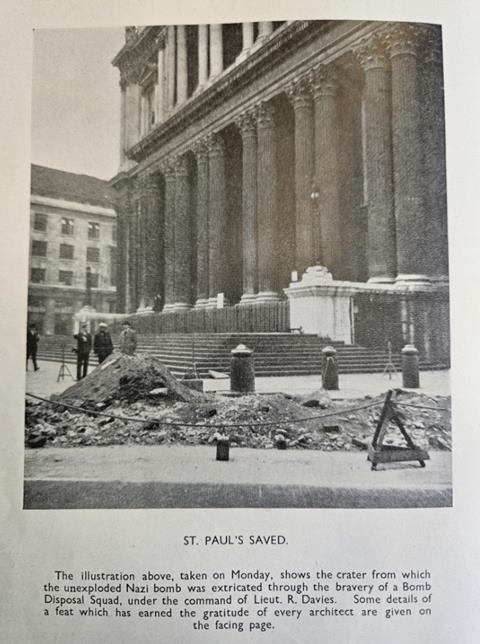

News story, 20 September 1940

The Bomb at St Paul’s

ONE of the biggest bombs to be dropped on London fell in Dean’s Yard, close to the west end of St Paul’s Cathedral, entering the roadway at the edge of the pavement. For three days a bomb disposal section of the Royal Engineers, under the command of Lieut R Davies, worked on its removal.

When they began to dig they found that a 6in gas main had been fractured and three men were gassed at an early stage. The gas company were called in to deal with the main, which had caught fire. No one then knew how close to the flaming main the bomb might have been.

When the gas had at last been cut off, the bomb disposal section had to dig for 27ft 6in into the subsoil before they found the bomb. It proved to be a ton in weight, and looked like a vast hog, about 8ft long. Moreover, it was fitted with fuses which made it deadly dangerous to touch or move it.

To save devastating damage to St Paul’s, the risk of removal had to be undertaken, and with great difficulty it was drawn up with special tackle, for high polish had been imparted to it in its passage through the soil, making it difficult to handle.

Two lorries in tandem were required to haul it out of the hole. The streets were cleared by the police from St Paul’s Cathedral to Hackney Marshes. The bomb was placed on a fast lorry and driven away by Lieut Davies at high speed, the risk of explosion being imminent all the time.

At Hackney Marshes the bomb was blown up by the bomb disposal section. It caused a 100ft crater and rattled the windows, and in one case loosened plaster in houses far away on the Marshes.

Only the courage and tenacity of the officer, his NCOs and men prevented St Paul’s from being gravely injured, if not levelled to the ground.

We are glad to note the statement of Canon Cockin that the Dean and Chapter are taking steps to express their appreciation in suitable form. Special prominence has rightly been given to this extraordinary act of skill and bravery, but it is well to remember that it is typical of the routine work that the bomb disposal section is doing every day. The nation owes a debt of gratitude to these men that can never be repaid.

Bombed City Churches

SEVERAL famous churches in the City of London have been severely damaged by German bombs, though considering the great number of churches in this confined area it is astonishing that so few of them have suffered. Most of the destruction is limited to shattered windows and torn ceilings. Altogether, up to the end of last week, more than 20 churches have suffered some damage in the diocese of London.

Most of the violated churches in the City are the work of Wren (writes a special correspondent of The Times), and winding a way along the twisting passages, still full of smoke from smouldering fires, one can appreciate how remarkably they have been protected from the full blast of bombs by modern blocks of offices towering above everything but their lofty spires.

St Mary Abchurch has suffered more extensively than any other City church from a bomb that hit a high roof a few yards away. Every window has been carried away, hardly a slate remains intact on the roof, and the red-brick turret and the spire are deeply pitted with holes from splinters. Yet the fabric of the church is intact, although the interior was much impaired by blast and flying glass and masonry.

The dignified church of St Magnus the Martyr, standing near London Bridge, at the very heart of the Empire, also received much superficial damage.

Another remarkable aspect of these damaged churches is the way in which the heavier stained glass has been blown in where newer, plain glass a few feet away has not even cracked. This is especially the case at St Stephen, Walbrook, where not one of the stained lights portraying the Life of Christ has escaped nor a clear pane suffered. At St Swithun’s, Cannon Street, too, stained middle panels have been carried away, leaving the rest of the windows intact.

News story, 8 November 1940

Damage to London Buildings

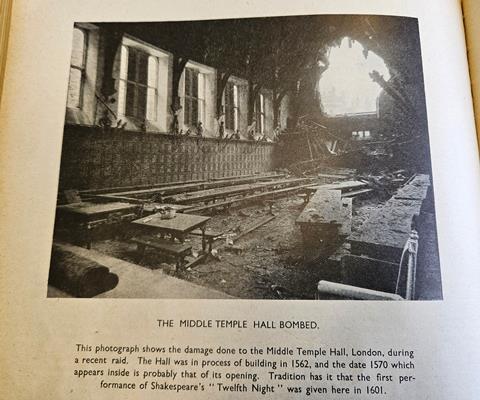

News has now been released of air-raid damage to more London buildings of historic or other interest.

To the list of damaged buildings must now be added Kensington Palace and Chelsea Hospital (both works by Sir Christopher Wren), while some damage has been sustained by certain houses in Kensington-square. The Palace has suffered from the action of incendiary bombs, which have damaged some of the apartments. At one place the building is roofless.

At Chelsea Hospital, high-explosive bombs damaged some of the wards, but the extent is not severe, we understand.

The Dutch Church in Austin Friars, which has been devastated, was built in 1250 as a monastery, chapel by the Augustinian (corrupted into Austin) Friars, and in 1550 was given by Edward VI to the “Dutch nation in London,” refugees from the Netherlands, as there are again today. The windows were good fourteenth-century work, and the arcades were of the fifteenth century. It is said to have had the largest floor space of any City church except St. Paul’s Cathedral. It was damaged by fire last century, and a few- years ago the roof and arches were restored.

The Roman Catholic Church of St Boniface, Whitechapel, which has been wrecked, was known locally as “the German Church,” because it served a German Roman Catholic colony.

At St Bartholomew’s Medical School, the roof of the refectory has been damaged by fire. The refectory was the great hall in the time of the Merchant Taylors” School, and was built in 1875 soon after it was taken over from Charterhouse.

Severe damage has been done to Stationers’ Hall, off Ludgate Hill, the beautiful home of the Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers, built in 1670 to replace that destroyed in the Fire of London. An incendiary bomb fell on the lobby of the court-room. The lobby and the north end of the hall have suffered severely, and the fine ceiling, on which is a representation of St. John the Evangelist, has been badly damaged.

Damage has also been done to the Centre Court at WImbledon, and Thurston’s, in Leicester Square, headquarters respectively of lawn tennis and of billiards.

Extract from leading article, 29 November 1940

REBUILDING

THAT we should even be thinking of the making good of war damage while still preoccupied with war-making may be taken as a symbol of our unbounded confidence in the final result. If the shadow of defeat had fallen across the prospect no such dreams of the future could have been entertained for a moment.

At the same time, we should do well to remember that we are preoccupied with war-making, and that it will be very easy to commit ourselves to the wrong course if we do not all interest ourselves in the prospect. Steps could be taken which it would be hard to retrace, and policies might take a definite shape such as we should not welcome had we the time to give to this problem of the future alone.

A great deal will depend upon the shape which will be taken by our social order and our economic structure after this great upheaval has run its course, and until then it is difficult to say upon what lines our plans should be directed. It may well be that we shall find ourselves, without dispute, and without revolution, in the ordinary sense of the word, a Socialist State, in which every citizen will be a servant of, and paid by, the State. Or it may be that some way will be found to maintain the more individualistic scheme of things to which we are used. More probably it will be some compromise between one thing and the other, whereby the State will stiffen its control while leaving the general system of private ownership to survive.

If, indeed, we were committed to the Socialist State, the rebuilding of towns and cities would be a job for the Civil Servant, and there would be no further argument about that aspect of the question. But if there is to remain any element of private ownership and individualism, then the old question between private practice and official architects looms up in its most acute form. To determine where the field of one form of architectural practice begins and where the other ends will certainly be no easier than it has been hitherto.

News story, 20 December 1940

NOTES AND NEWS

Destroyed Buildings

BUILDINGS which have been damaged or destroyed by recent Nazi raids include the University Great Hall, St Peter’s Hospital, the Dutch House and Temple Church, Bristol. The Great Hall is little more than a heap of rubble, and St Peter’s Hospital (which is a half-timbered building) was also destroyed, as was the Temple Church, which is roofless and windowless, but whose leaning tower still stands. The old Crown Court at the Guildhall has also been destroyed, but the new Civil Court is undamaged. Birmingham Midland Institute has also suffered severely, but is still in use.

Another recent sufferer is Eton College, which has twice been bombed. Very little is left of Savile House, which was part of a row of picturesque houses at the corner of Weston’s-yard, built in 1604 by Sir Henry Savile. The 250-year-old Upper School has also been hurt, but not irreparably. Minor damage has been done to other buildings, but the structure of the Chapel, Lupton’s Tower and the Lower School is unharmed.

Coventry Cathedral: Extent of Damage

ACCORDING to the Very Rev RT Howard, Provost of Coventry, what is now left of the Cathedral (following the Nazi attack) are the encircling outer walls of all the guild chapels and the sanctuary in an unbroken line completely enclosing the ruins of the nave, chancel and side aisles. The walls of the five-sided apse are all standing, but the traceries are slightly damaged.

The ruins of the nave arcade lie piled up in two long lines from west to east, so that one can walk from the west to the sanctuary almost unhindered. The tower and spire are blackened on the side where the volumes of smoke engulfed them for a night, but otherwise they are as strong as ever. All the ancient woodwork of stalls and screens has perished, but the high altar cross and candlesticks were saved, and all the Communion vessels. Coventry Cathedral, begun in 1373, was completed in 1450.

Leading article, 10 January 1941

THE FUTURE

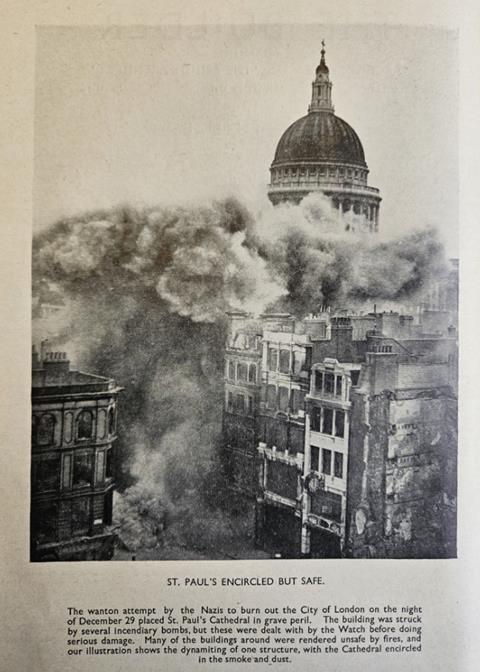

HAVING survived a year of dire peril - perhaps the direst in our history - we face the New Year with a full realisation of the grim nature of the task before us, but quietly confident in our ability to withstand whatever may be in store. The Germans have shown us that their threat of total war was no empty one. We have seen our most treasured historic buildings, our churches, our hospitals, our homes go up in flame and smoke or crash to the ground in heaps of ruin before the insane onslaught from the skies.

It has been left to the Germans, with all their claims to culture and racial superiority, to pursue deliberately a policy of indiscriminate destruction, to rain death upon defenceless civilians, to destroy fine buildings of no military importance, and to attempt to engulf whole cities in flames. By their actions they have shown themselves to be worse than barbarians and have earned the contempt and loathing of the civilised world. “Let them relearn the law.”

We must expect and prepare for destruction far surpassing anything that has yet happened. Great areas of our towns and cities may be wiped out. While this may simplify the task of replanning after the war, it raises many questions of detail that will have to be settled before any attempt can be made to plan anew.

There is the case of the City Churches, for example, several of which have been severely damaged or partially destroyed. Should they invariably be rebuilt? The controlling consideration must, we think, be the new plan, though, it is clearly impossible to lay down hard-and-fast rules on such a complicated subject.

On the ethical aspect of the question, where substantial parts of a church remain and there is no insuperable planning or other objection, few are likely to say that it should not be rebuilt. But where a building has been completely or largely demolished, is there any merit in setting up a copy in its place?

Facsimile reconstruction may show us the outward appearance of what existed before, but it can never recapture the spirit nor be anything more than a copy, almost wholly lacking the interest and value of the original. We do not pretend to dogmatise on a subject so full of difficulty and on which there is bound to be a great diversity of well-founded opinion. We suggest that the bodies most competent to offer guidance and the subject - the Royal Fine Art Commission and the R.I.B.A., for example - might well explore the whole problem with a view to giving a lead to all concerned.

As to replanning in general, Lord Reith, the head of the recently created Ministry of Works and Buildings, has been charged by the Cabinet with the responsibility of “consulting the departments and organisations concerned with a view to reporting to the Cabinet the appropriate methods and machinery for dealing with the issues involved.” Such an opportunity of substituting order for chaos should be taken advantage of to the fullest possible limit, but a method of overcoming the many obstacles that stand in the way of comprehensive replanning has yet to be found.

Vested interests and short-sightedness perpetuated the medieval plan of London after the Great Fire, and they still stand in the way of ordered progress. No removable obstruction, either material or legal, should be allowed to defeat the opportunity for comprehensive replanning, not only in London, but generally throughout the country, which will be presented to us at the end of the war.

In the meantime we may congratulate Lord Reith on the excellent start he has made on his enormously difficult task by gathering around himself a body of technical experts, particularly a number of highly competent architects and engineers of wide experience. The appointment by the Building Industries National Council of a small but fully representative committee under the chairmanship of Sir J Walker Smith to ensure effective liaison between the industry and the Ministry is also a welcome step.

It is evident that there must be much more direct contact between the industry and the Government, particularly with regard to the increased call for more and better shelters and to the necessary replacement of buildings damaged by enemy action. There is an increasing realisation of the need for the industry to forgo its separatist outlook and to co-operate wholeheartedly if its maximum contribution to the national war effort is to be made.

There is a great deal to be done, too, in the organisation and rationalisation of building materials manufacture. The appointment of Mr TS Tait as Director of Standardisation to the Ministry of Works and Buildings is an indication of the importance attached to this section of the building industry, not only for the duration of the war but after. So also must there be a larger measure of co-operation on the professional side.

At no other time in all our history has the building industry stood in so vital a relationship to the State. It is no exaggeration to say that the winning of the war may in large measure depend upon its efforts. The industry, we may be sure, will neglect no means of intensifying those efforts, so that the year 1941, if it does not see the end of the war, may yet make a prodigious contribution towards victory and the restoration of Peace.

More from the archives:

>> Nelson’s Column runs out of money, 1843-44

>> The clearance of London’s worst slum, 1843-46

>> The construction of the Palace of Westminster, 1847

>> Benjamin Disraeli’s proposal to hang architects, 1847

>> The Crystal Palace’s leaking roof, 1851

>> Cleaning up the Great Stink, 1858

>> Setbacks on the world’s first underground railway, 1860

>> The opening of Clifton Suspension Bridge, 1864

>> Replacing Old Smithfield Market, 1864-68

>> Alternative designs for Manchester Town Hall, 1868

>> The construction of the Forth Bridge, 1873-90

>> The demolition of Northumberland House, 1874

>> Dodging falling bricks at the Natural History Museum construction site, 1876

>> An alternative proposal for Tower Bridge, 1878

>> The Tay Bridge disaster, 1879

>> Building in Bombay, 1879 - 1892

>> Cologne Cathedral’s topping out ceremony, 1880

>> Britain’s dim view of the Eiffel Tower, 1886-89

>> First proposals for the Glasgow Subway, 1887

>> The construction of Westminster Cathedral, 1895 - 1902

>> Westminster’s unbuilt gothic skyscraper 1904

>> The great San Francisco earthquake, 1906

>> The construction of New York’s Woolworth Building, 1911-13

>> The First World War breaks out, 1914

>> The Great War drags on, 1915 - 1916

>> London’s first air raids, 1918

>> The Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building, 1930

>> The Daily Express Building, 1932

>> Outbreak of the Second World War, 1939

No comments yet