The recently rebranded Building magazine recounts the challenges of building one of the UK’s last great church projects

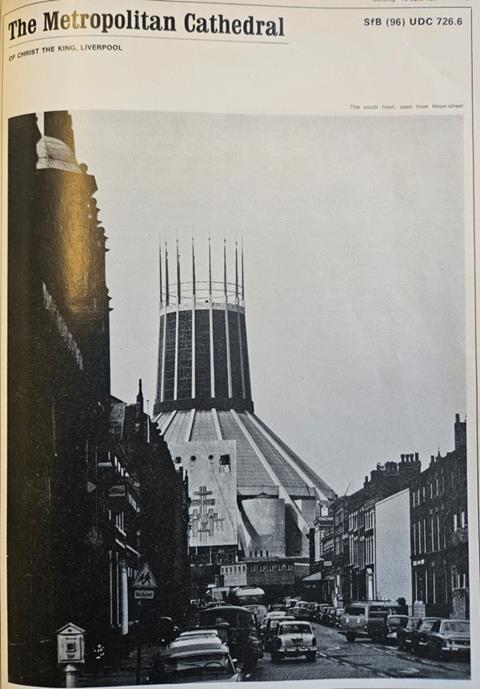

The construction of Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral started in October 1962, the same month in which the Beatles released their first official single, Love Me Do. The cathedral was completed five years later, in the same month the Merseyside band released its era-defining album Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

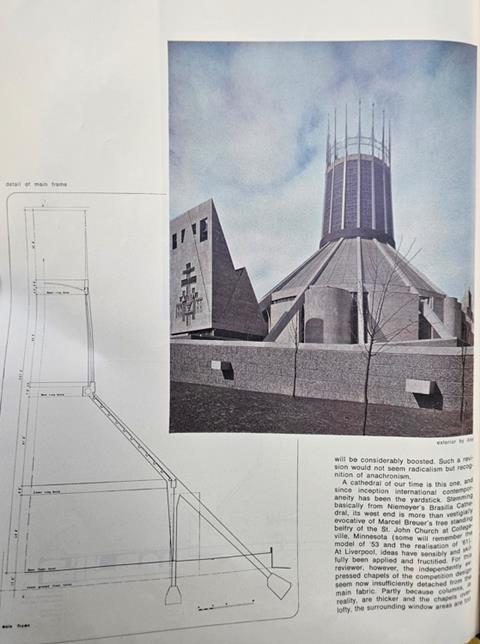

Just like the fab four, the modernist landmark was a symbol of Liverpool’s cultural revival following the hardships of the Second World War and the 1950s. Designed by Frederick Gibberd and built by Taylor Woodrow before the contractor pivoted towards housebuilding, the now grade II*-listed Catholic cathedral was also one of the UK’s last great church projects of the 20th century.

Below is the coverage that appeared in Building – renamed from The Builder the previous year – of the cathedral’s opening in its June 1967 issue, including an introduction by George Andrew Beck, the archbishop of Liverpool, and part of a feature looking at how it was built.

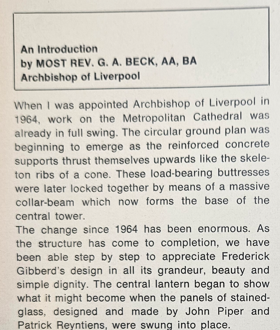

Introduction by George Andrew Beck, archbishop of Liverpool, 16 June 1967

When I was appointed Archbishop of Liverpool in 1964, work on the Metropolitan Cathedral was already in full swing. The circular ground plan was beginning to emerge as the reinforced concrete supports thrust themselves upwards like the skeleton ribs of a cone. These load-bearing buttresses were later locked together by means of a massive collar-beam which now forms the base of the central tower.

The change since 1964 has been enormous. As the structure has come to completion, we have been able step by step to appreciate Frederick Gibberd’s design in all its grandeur, beauty and simple dignity. The central lantern began to show what it might become when the panels of stained glass, designed and made by John Piper and Patrick Reyntiens, were swung into place.

William Mitchell’s sculptures on the belfry brought a further bold and beautiful element into the picture. The bells themselves were blessed and hoisted into position. Perhaps the most satisfactory moment came when the pinnacles over the lantern were finally in place, and one realised how the former structure of strength and dignity. had been transformed into a thing of quite unexpected grace.

The outside of the building, however, is merely an introduction - or rather an invitation - to come inside. If possible you must go in through the main doorway - another powerful piece of work by William Mitchell. You go under the entrance porch and through a passage-way to come out into the breath-taking space of the central nave. One is struck by the vastness of the great conical structure, the superb stained glass and the subtle variations provided by the periphery of side chapels, each different from the others in appearance and construction. In the centre of the building under a suspended baldacchino is the high altar of white marble, the focal point of the whole building. Even the design of the floor in grey and white marble leads the eye to this central feature. As you stand in the entrance porch, facing the high altar, you see beyond it, on the opposite side of the building, the entrance to the Blessed Sacrament chapel. This chapel, with its stained glass windows, and a vivid reredos by Ceri Richards standing out above the glowing tabernacle, is in striking contrast to the somewhat quieter tones of the main nave.

These are no more than a few of what may be called the client’s impressions. The archdiocese and the City of Liverpool have been enriched by a remarkable building, setting a new standard in ecclesiastical architecture. We must thank all those who, by their creative genius or their technical skill, have brought to reality our dream of a new Cathedral. To the architect and his colleagues, to the artists, craftsmen and workers of all kinds, we owe a debt of gratitude. The Taylor Woodrow Construction team must be well-satisfied with this remarkable achievement.

Extract from feature, 16 June 1967

A building like this has a life of its own, a personality, a temperament, even before anything concrete appears above the ground. While schools and colleges and blocks of flats remain a dead pile of prefabricated units snugly and securely fitting the one into the other, borrow their life from the occupants when they move in, and, perhaps, over the years, take on the shadow of a character, the Cathedral has been alive from the beginning, has made its character felt from the first working drawing.

The few constructional aspects of the Cathedral selected here may indicate the unusual sort of problems that the building presented and the way that these were tackled and resolved.

The problems inherent in a circular building of some size for an architect’s office can never be fully appreciated until the job comes to be done. The basic dimensions are all agreed, the plan, the profiles, it is in coming to actually detail - for example - the confessionals which screen three of the side chapels from the nave. They have always been there on the small scale plans, logically enough, on either side of the chapel entrance. But their front face is a chord to a curve at 97 ft. 6 in. radius from the centre of the High Altar and the rear face to the chapel is at 103 ft. 6 in. radius: one end wall is directly radial, the other parallel with the radial wall of the chapel and about 7 ft. 6 in. away, the centre point, of course, is some 2 yds. in space beyond the drawing board. Railway curves were the answer to these difficulties, their numbers related to radii and scales and circulated to the drawing team. But they did not solve the problems of dimensioning, nor of calculating the areas or lengths of materials required.

This sort of difficulty recurred and with much greater force on the site. The basic setting out was deceptively simple, a centrepoint on a line produced from the centreline or the existing crypt and the right distance from it; a splendidly large and important peg was concreted in a muddy expanse of bulldozed ground. But at what point does one dig in undulating ground for the foundations of a flying buttress set at 45 deg. to the horizontal plane of the floor? The foundation for one buttress was expected to be tricky, a large provisional sum was set aside for it, and it did not fail us. This was a buttress set to miss penetration into the existing crypt by just 6 in. but which, because of its 45 deg. inclination, must find its rockface upon which to bear somewhere beneath the crypt floor. It happened to coincide with an old quarry from which perhaps some of the sandstone for the old workhouse buildings which once covered the site had been dug. The excavation continued down through the formless mass concrete foundations of the crypt, and on through rubble. At the point where excavation began to turn into an underground shaft, a specialist mining subcontractor was brought in, a firm used to carrying out particularly tricky and difficult works beneath the ground. They found solid and undisturbed rock 90 ft. down where daylight failed and one was indeed underground.

Even worse, high up, in air which was never still, formwork must be positioned for the columns of the tower. There are 18 columns equally spaced around a circle between which precast panels of coloured glass framed in concrete must fit; each column tapers a few inches in width in the height of the tower, and additionally inclines inwards by a few degrees to produce the tapered profile of the tower itself. Each column is surrounded by a jungle of scaffolding, bleak and windswept, and one reaches it in some distress after quite testing physical exertion. Where is the slot that will take the washer of the bolt that will hold the bottom left-hand corner of lantern panel number 146?

The knowledge that each column and the connections of the lantern panels to them were designed to allow for both independent movement of one column in relation to its neighbours and for example a whole group of columns on the windward side flexing inwards - each to differing degrees of movement - while those on the opposite side of the lantern flexed outwards under suction forces, heightened the sense of unreality about their true position in space. Even the theoretical and calculated spot seemed merely a place of temporary abode. For the architect in the midst of these awe-inspiring feats of structural engineering and construction it is comfort finally to find this slot or that long groove for a water bar.

A most important and far-reaching problem at the stage of detailing the building was the choice of materials to be used. It was accepted from the beginning that any material fit for its purpose could be employed; there was no spiritual bar to the use of materials not previously associated with Cathedral buildings. Indeed, this freedom was clearly stated by the decision to use reinforced concrete for the frame itself.

But the need for longevity not only in the structure but also in the finishes and the tight limits of cost within which to work produced a long series of problems. The life of the building should be infinite and many parts of the structure and finishes would become virtually inaccessible once the construction was finished. In these circumstances was the paper-thin damp-proof course used without trouble on many previous contracts adequate? The paint-faced hardboard was the right colour and had the right acoustic responses but the manufacturer did not know if it would last 100 years and more; the question had not been asked before since it was mostly used for cupboard fronts in low-cost housing.

When materials are questioned and explored in this way, relatively few can be accepted at once to have an indefinite life. Many more must be explored and checked before acceptance, and many must be rejected.

Furthermore, materials were being used and detailed with which acquaintance tended to be limited; a marble floor of 200 ft. diameter, for example, is not a common feature of building construction in this century. The floor upon which it was to be laid was the suspended concrete slab which forms the roof of the car park below, a 2 in. layer of foamed concrete to insulate the nave from the unheated space below, and a 2 in. dry dense concrete screed within which the copper floor heating coils were accommodated. An allowance of a further 2 in. was made for the floor finish - the material was selected after the building work started.

Marble was the eventual choice and a saving was made by accepting the standard Italian thickness of just over 1 in. This was laid upon building paper to make it independent of the heated screed beneath and the bed for the marble was continuous and reinforced with chicken wire. Expansion joints were introduced, both radial and circumferential, by increasing the normal 1/8 in. joint to 3/16 in, and filling this with an elastic material. There was no clear precedent to follow in all this but the final specification emerged after discussions with all the specialists.

In this category of unusual materials - at least for most architects’ offices - Portland stone must be included. The choice of this material to face the walls and chapels and porches was made on the basis of colour and of its self-cleansing properties where washed by rain. It will weather satisfactorily in the somewhat doubtful atmosphere of Liverpool.

More from the archives:

>> Nelson’s Column runs out of money, 1843-44

>> The clearance of London’s worst slum, 1843-46

>> The construction of the Palace of Westminster, 1847

>> Benjamin Disraeli’s proposal to hang architects, 1847

>> The Crystal Palace’s leaking roof, 1851

>> Cleaning up the Great Stink, 1858

>> Setbacks on the world’s first underground railway, 1860

>> The opening of Clifton Suspension Bridge, 1864

>> Replacing Old Smithfield Market, 1864-68

>> Alternative designs for Manchester Town Hall, 1868

>> The construction of the Forth Bridge, 1873-90

>> The demolition of Northumberland House, 1874

>> Dodging falling bricks at the Natural History Museum construction site, 1876

>> An alternative proposal for Tower Bridge, 1878

>> The Tay Bridge disaster, 1879

>> Building in Bombay, 1879 - 1892

>> Cologne Cathedral’s topping out ceremony, 1880

>> Britain’s dim view of the Eiffel Tower, 1886-89

>> First proposals for the Glasgow Subway, 1887

>> The construction of Westminster Cathedral, 1895-1902

>> Westminster’s unbuilt gothic skyscraper 1904

>> The great San Francisco earthquake, 1906

>> The construction of New York’s Woolworth Building, 1911-13

>> The First World War breaks out, 1914

>> The Great War drags on, 1915-16

>> London’s first air raids, 1918

>> The Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building, 1930

>> The Daily Express Building, 1932

>> Outbreak of the Second World War, 1939

>> Britain celebrates victory in Europe, 1945

>> How buildings were affected by the atomic bombs dropped on Japan, 1946

>> Rebuilding the House of Commons chamber, 1945

>> Planning the postwar New Towns, 1945-46

No comments yet