Architect rejects claim that a bad brief led to a poor scheme

David Adjaye has rejected criticism of his Holocaust Memorial which was levelled by one of the country’s most prominent architecture writers at a public inquiry.

The architect said he was stunned by Rowan Moore’s argument that a bad brief had led to a poor design.

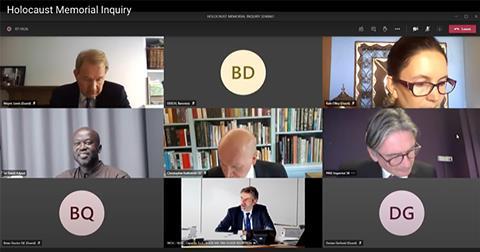

Adjaye, who was named winner of the 2021 Royal Gold Medal last month, was giving evidence in the third week of a public inquiry into controversial plans for a memorial and subterranean education centre in Victoria Tower Gardens next to the Palace of Westminster.

The memorial was designed by Adjaye Associates with Ron Arad Architects and Gustafson Porter & Bowman who won a design competition in 2017, beating McAslan, Foster, Studio Libeskind, Zaha Hadid Architects and Caruso St John, among others.

It has been reworked several times in a bid to minimise its impact on the gardens and the wider Westminster Unesco World Heritage Site. In November last year the project was “called in” for ministerial approval, despite the apparent conflict of being promoted by the Communities Ministry (MHCLG).

Opponents include Westminster council, local residents including architect Barbara Weiss and leading Jews. They have argued it is the wrong place for such a memorial, that it would overwhelm the gardens and yet not be big enough to do justice to its subject, and that it would be a terrorist target. The inquiry is set to last five weeks.

Yesterday Christopher Katkowski QC, the barrister representing the Secretary of State as the project’s promoter, summarised Moore’s evidence as: “Brief bad = scheme poor”.

Addressing Adjaye, he continued paraphrasing Moore, an author and the Observer’s architecture critic: “However good the architect is – and he did have one or two words of praise for you, Sir David – you were never ever going to be able to do anything worthwhile with such a bad brief.”

Adjaye responded: “I was stunned when I heard that because the very premise of my profession is to find solutions to ever-changing typologies and forms.

“What excited us about this project was this idea of having not just a memorial you go to in the traditional sense but one you can [also] enter to experience a learning centre.

“I don’t know a single memorial in the whole world where that happens – I don’t say that lightly – where you go through the memorial into a learning centre, which I think is a very profound evolution of this way of memorialising and understanding education: both a memorial and a gateway to an illumination of information.

“We thought that was profound and a shift in the idea of memorials and one that made a lot of sense in the landscape. [We felt this] was what good architects do: we rise to that challenge where we see that opportunity and we interpret it for the world that we live in.

Adjaye Associates’ interest in memorials was the subject of the Making Memory exhibition at the Design Museum last year.

Addressing the virtual inquiry from Accra, Ghana, he said: “The proof is in the built form in the end.” He drew a parallel with his Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington.

“I was told there were only white stone buildings on the Mall and proposing a bronze building was absolutely the wrong thing to do; it was out of context,” he said. “Now that building is celebrated as being a key contributor to the understanding of that context.” Its difference from its neighbours on the US capital’s ceremonial avenue shone a new light on the way we see familiar things, he said.

The very premise of my profession is to find solutions to ever-changing typologies and forms

David Adjaye

Adjaye was also questioned about the positioning of the Holocaust Memorial within the listed garden and asked whether a playground and other monuments should be moved.

He revealed his children use the playground as his family lives in Westminster. The consultant team concluded it should stay so families could talk to their children about the meaning of the monuments.

The garden contains several other memorials – among them to suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst, Rodin’s self-sacrificing Burghers of Calais and the Buxton Memorial Fountain commemorating the abolition of slavery – that talk about important ideas rather than memorialising “men on horses”, he said.

Adjaye described the positioning of all the monuments as “critical” and said by not moving the Buxton fountain and adding benches with views of both they would improve the setting and “lend more weight to the discussion of the two monuments”.

He added: “It offers a wonderful moment to look at two memorials in a really very powerful and special way that we felt would help both memorials and for us would concretise this idea of the landscape being a garden of consciousness of the nation.”

Katkowski – who was recently an official advisor to the government on its planning reforms – also asked about Moore’s suggestion the garden contained a “clutter” of materials, shapes and forms, old and new.

Adjaye said his scheme would “organise the space” into a sequence of monuments and that they were proposing to use materials such as bronze and stone that were already found in the gardens.

The memorial was announced in 2016 by then prime minister David Cameron who said it would be dedicated to the six million Jews and other victims murdered by the Nazis in the Second World War.

He is due to face further cross-examination today.

No comments yet