The National Gallery’s grand new entrance could never have happened without the services that were artfully installed behind the scenes, says Andy Pearson

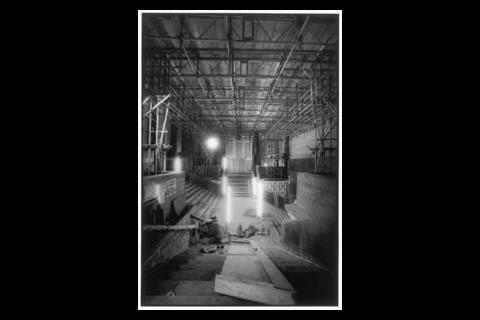

Later this month, amid much pomp and ceremony, the doors of the National Gallery’s grand porticoed entrance on Trafalgar Square will open to reveal a dramatic new entrance lobby. In less than a year the hall has been remodelled into a single entrance large enough for information desks and audio guides. Below the entrance, on the ground floor, is a new multi-media area and coffee bar with toilet facilities.

The redevelopment is the latest phase of a masterplan by architect Dixon Jones to provide a cohesive internal layout, improve the logic of the circulation and enhance the display galleries. But transforming a gallery, originally constructed in 1838 for 200,000 visitors a year, into a world-class destination for 5 million people is not easy, as Howard Hall, mechanical engineer at services engineer Andrew Reid & Partners attests. “The public will not be aware of the pain and agony of getting to this point,” he says.

Andrew Reid has been working with the National Gallery since the redevelopment’s inception. From the services engineer’s perspective the project is complex because services have had to be maintained throughout to protect the artworks and enable the galleries to stay open. “The basement ceiling was covered in services … and the architect would say: ‘We’ll cut through all of those to create a space here,’” recalls Tony Nijhuis, project engineer at Andrew Reid.

The engineer’s task was further complicated because infrastructure, including drainage and power supplies, installed during early phases had to have sufficient capacity for later phases to proceed without the need to return and do more work to completed areas.

“The biggest challenge was replacing the 100-year-old drainage system running beneath the building,” says Nijhuis. This involved tunnelling beneath the basement to lay a 400 mm diameter drain to transfer rainwater and sewage from the building to an existing sewer in St Martins Lane to prevent the basement flooding.

Equally challenging was the relocation of the 70-year-old electrics: “They were an absolute nightmare,” says Nijhuis. The engineers had to enable the relocation of an 11 kV transformer, switchgear and cables to rationalise and replace the existing electrical distribution and meet the increased electrical load of the new spaces.

Putting a roof over an existing lightwell created one of the new spaces, the Annenburg Court. However, enclosing this space and the new Central Hall meant cooling was required. But with nowhere to house the plant the engineers had to take the costly and time-consuming option of excavating a plantroom under the Court.

As this phase of the project nears completion, Nijhuis is pleased with the results. “Services infrastructure may not have the same kudos as the creative architectural aspects, but they’re the lifeblood of the building,” he says. “We’ve produced a highly specified services design … with sensitivity to a historic landmark building.”

Source

Building Sustainable Design

No comments yet