The 2006 Winter Games in Turin left a legacy of colourful architecture and were judged the greenest Games ever by the UN. Stephen Kennett investigates what lessons can be learnt for London's Olympic Village

When London came from being a rank outsider to first past the post with its bid to host the 2012 Olympics, it was in part due to two crucial issues: sustainability and legacy.

Its winning bid made much of plans for on-site power generation, reductions in construction waste and the use of environmentally responsible materials, as well as measures to protect and enhance the surrounding wildlife and ecology. And after the Games, the venues would provide a lasting legacy, either by being reconfigured or dismantled and reused elsewhere.

While the organisers were keen to avoid the legacy pitfalls that blighted other Olympic Games, notably Athens where following the 17 days of events venues have remained empty and unused, there is perhaps one example that London could look to emulate – Torino 2006, host to the most recent Winter Games.

The United Nations Environment Programme has recently judged this as the greenest Games ever with particular reference to the Olympic Village and its “development of eco-friendly buildings and the use of pollution-free materials in their construction”. Over the next two pages we look at the key features that influenced the design and construction of the £90 million village, which was developed by an international team of designers coordinated by Italian architect Benedetto Camerana, with M&E design and sustainability advice from Faber Maunsell in the UK.

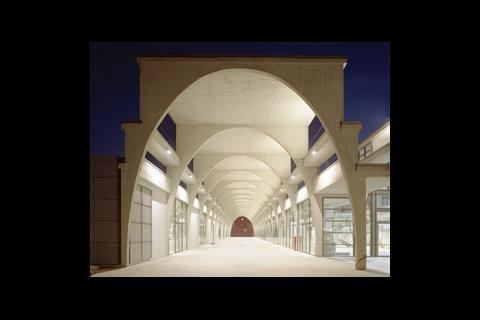

Linking the site to the city

What makes a good Olympic Village? Some of the key issues are that it should be a restful place for the athletes, traffic free, and have easy access to retail, social and training facilities – ideally within walking distance. These are features that also help sell a complex after the event.

But there was a problem with the site earmarked for the village in Turin. Situated about 3 km to the south of the city centre, the brownfield site was in an area of Turin that was crying out for regeneration. However, “The site was very much an island,” says Mike Maslin, regional director with Faber Maunsell. “It was cut off from the city by the railway tracks and a huge marshalling yard.” The solution to this problem was to construct a bridge, spanning the rail lines to the Lingotto Fiere, Turin’s congress and exhibition centre.

This isn’t your typical pedestrian bridge. Designed by Hugh Dutton, the 340 m pedestrian bridge, with its distinctive 70 m arch, became one of the enduring symbols of the Games. As well as acting as one of the key access routes for athletes, it now links the village to the Lingotto Fiere where Fiat cars were produced until 1982. After this date, the factory was transformed into the bustling complex of hotels, conference facilities and shopping centre seen today. “In the long term it will help create a new urban centre for Turin,” says architect Benedetto Camerana.

Reusing the existing buildings

Formerly a wholesale fruit and vegetable market, the site included a series of listed 1930s buildings designed by the architect Umberto Cuzzi. Originally open to the elements, the buildings were earmarked to provide 25,000 m2 of enclosed and covered areas, hosting such facilities as conference rooms and a medical centre.

To preserve the structures, self-supporting glass facades, set back from the roofline to create an element of solar shading, were installed and in the taller spaces free-standing mezzanine levels provided an additional floor area that could easily be removed at a later date.

For the services, Maslin says they wanted to take advantage of the exposed mass provided by the structure. The spaces are mechanically ventilated, with the air-handling plant concealed in the trough between the concrete wings of the roof. Ventilation, air is pulled in from the south side through glazed double skin facade, which help preheat the air. The services design follows the criteria set by the Olympic Committee, which meant there was no cooling requirement for the winter period when the buildings would be occupied. Future tenants can retrofit cooling plant if it's needed. There was always a compromise to be struck between being amenable to different future uses, and cost, Maslin says.

The facilities now stand empty but a deal has been done with the expanding Polytechnic of Turin to take space, while other units are earmarked for incubator businesses and retail.

The dwellings

One of the main design aims was to create a space people would want to live in after the Games. Success in the latter is already evident with the social housing elements now occupied, while the private apartments will soon go onto the market.

Within strict criteria for the size and number of people the apartments had to house, as set by the Olympic authorities, the architects created a masterplan for the 750 apartments, where 2,500 athletes and support staff would initially live.

In all there are 35 individual residential units within the city blocks, each between five and eight storeys high, and set out in a chequer board pattern. Each lead architect then had a free hand with the mix of apartment layouts and sizes.

The building envelopes are constructed with a high degree of thermal insulation to reduce heat losses in the winter to less than half of those permitted under Italian regulations. Daylighting and solar gains are maximised in some of the apartments in colder months by wintergardens. These collect heat energy during the day and release it into the interior at night, while in the summer the windows can be opened but are screened with sunshades to increase the exchange of air and provide cooling.

The apartments are heated by an underfloor system that takes LTHW from the district heating system, while 1,800 m2 of solar thermal collectors are used for the hot water load.

Sustainability guidelines

The Polytechnic of Turin drew up Guidelines for Sustainability in Design, Construction and Operation of the Olympic Villages, which was adopted as the reference handbook for the design competitions and proposals for engineering services for the six Olympic Villages. The sustaianbility measures were broken down into seven key areas and assessed (see the ‘sustainability wheel’, opposite). The design achieved an overall score of 71 out of 100, below are some of the key features.

Water

Rainfall in Turin is high – neighbouring Milan gets twice the rainfall of London in an even shorter period – making flooding a real issue. To help alleviate this the surface water drainage volumes were reduced by 30% compared with similar sites, by the use of permeable hard surfaces, rainwater harvesting and attenuation.

The site’s industrial past helped with the attenuation: the design team has simply reused some of the underground air-raid shelters left over from the Second World War when the adjacent Lingotto factory was a target for bombers for water storage. “They turned out to be ideal and not much worked was involved,” says Maslin. “It was simply a case of installing the pumps, valves and switching really.”

Water consumption was reduced by almost a third by the specification of low-flow appliances, spray taps and low-flush toilets, while rainwater from the rooftops is channel- led into two underground tanks and used for irrigation.

Waste

Wherever possible materials were reused. This included the granite pavers around the central buildings, aggregate from buildings unsuitable for reuse and uncontaminated soil for level changes. Segregated waste disposal containers were provided and suppliers’ packaging was reduced. Material such as PVC, synthetic fibreboards, adhesives and those with prolonged off-gassing properties were excluded or reduced.

Local sourcing was prioritised. "On the M&E side that wasn't too difficult, Northern Italy has an abundance of manufacturers for air handlers, thermal wheels and the like,” says Maslin and there was an attempt to specify materials with low-embodied energy – though he admits success at this was limited.

Energy

To avoid the propensity for things to be lost or value-engineered out during construction, most of the sustainability measures were integrated into the building fabric. “I think if we’d covered the roofs in photovoltaics or wind turbines we would have seen them evaporate,” Maslin says.

Passive measures to reduce energy consumption included increased thermal insulation, solar shading and the use of ‘winter gardens’ to preheat ventilation air and trap solar gains in the winter months. Roof-mounted solar thermal panels covering an area of 1,800 m2, generate 20-25% of the heating and domestic hot water requirements for the housing and, like many cities in northern Italy, the village taps into Turin’s district heating system which provides the remainder.

Source

Building Sustainable Design

No comments yet