Last week saw one last Olympic 2012 victory for Team GB - the relaxation of the Olympic No Marketing Rights Protocol. What it will mean for those UK firms that took part?

Last week the January gloom lifted a little and the beleaguered UK construction industry was reminded of its glorious achievement last summer.

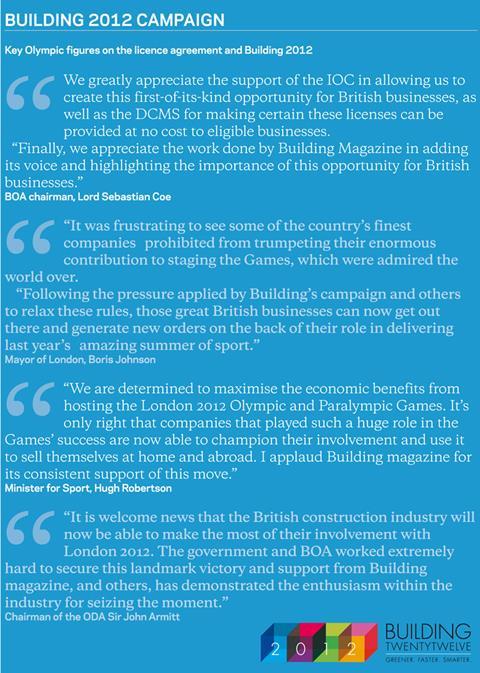

In a move hailed by prime minister David Cameron among others, the government announced that it had agreed a deal with the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to allow firms which worked on the London Olympics to circumvent a dreaded 32-page set of marketing rules known as the No Marketing Rights Protocol.

The landmark agreement - lobbied for throughout last year by this magazine’s Building 2012 campaign - means that, under the so-called Supplier Recognition Scheme (see overleaf), all 2012 suppliers can apply for a free licence from the British Olympic Association to fully promote their Olympic performances.

The government predicts the licence will provide a “significant boost” to the UK economy as part of the £13bn worth of Olympic-generated economic activity expected over the next four years.

But just how useful will the licence prove to be for construction firms trying to win new work off the back of their Olympic achievements? What type of businesses will benefit most and where? And what are the views of clients, contractors, Olympic sponsors and the firms themselves?

Better late than never

Talking to 2012 businesses there is clear consensus that the licence scheme is a positive and meaningful step, despite frustration at how long it has taken to formulate. Roger Hawkins, director and co-founder of architect Hawkins Brown, says the benefits are likely to go far beyond work on future sporting events. A previous critic of the marketing rules, Hawkins’ practice designed the £110m redevelopment of Stratford station for the Olympic Delivery Authority (ODA) and he is optimistic that his new-found freedom to communicate will boost his firm’s chances of picking up new rail work including potentially on London’s current mega project, Crossrail.

“It’s better late than never,” he says. “It’s important for us because we’re going for new projects and potential clients are always keen to know your track record.

“It’s important that we’re able to give an explanation of what we’ve done. Up until now, when we’ve produced marketing brochures, we’ve had to be quite vague about our work and on our website we’ve not been able to go into detail or show photographs - our Olympic work has been kept under wraps.

“I don’t think a lot of people know that we did a £110m project for the ODA.”

Until now we’ve had to be quite vague about our work and on our website we’ve not been able to go into detail - our Olympic work has been kept under wraps

Roger Hawkins, Hawkins Brown

While there is widespread recognition about the most famous firms behind Olympic projects - think Zaha Hadid’s acquatics centre, Thomas Heatherwick’s Olympic cauldron or the builder of the stadium, Sir Robert McAlpine - experts believe it is the lesser-known SMEs who will really benefit from the licence scheme.

Kevin Owens, former design principal at Locog who now runs design consultancy Owens Owens believes the licence agreement will prove valuable for years to come.

“This is a massive benefit - for all suppliers but especially for designers,” he says.

“It’s easy for the big names who designed the big venues but we wanted to help the smaller and middle-sized practices so that even projects that were considered and not built would be recognised.”

Owens gives the examples of Speirs + Major, which developed the Olympic lighting strategy, and architect AOC - which worked on 2012 telephone boxes - as firms whose little-known Olympic contribution can now be highlighted.

British firms are revved up for this. [London 2012] have been among the most aggressive brand-protectors in the world up until now

Graham Hand, British Expertise

He also underlines the value of the formalised nature of the scheme.

He says: “I had a lot of people come to me over the past seven years saying they had worked on Athens or Sydney and it was very difficult to clarify that.

“The purpose of this scheme is to ensure that those who did work on the London games could be officially recognised.”

A boost for Team GB

The licence agreement will probably attract some British developers but it is likely to be most valuable in impressing foreign clients.

While it has come a little late to influence the bulk of procurement on the 2016 Rio Olympics, there are hopes that it will come into play on later large-scale events such as the 2018 World Cup in Russia, the 2022 World Cup in Qatar, and the 2020 Olympics, which will be held in either Istanbul, Tokyo or Madrid.

The fruits of the deal could even be felt as early as next month under three sports-themed UK Trade & Investment (UKTI) trade missions to South Korea and Taiwan, Russia and Brazil, with big fish including Lord Coe among those travelling to the latter.

Graham Hand, chief executive of trade organisation British Expertise - which is organising the missions on behalf of UKTI - agrees the licence will have a “big effect” on firms’ work prospects.

“Companies will now be able to flash up images of what they have built and present statistics on what they have achieved,” he says. “There’s no doubt that British companies are revved up for this. They [London 2012] have been among the most aggressive brand-protectors in the world up until now.”

With Olympics construction firms suddenly able to unlock the restrictions which have bound them so tightly, could a golden legacy of world-beating success finally be within their grasp?

What’s next?

Three perspectives on the relaxation of the No Marketing Rights Protocol rules:

The client

Yair Ginor, director, Chelsfield Partners

This move will be most relevant to smaller providers who stand to gain from the cachet of the Olympics.

We tend to employ the best in the business in terms of architects and engineers so we are not waiting for the Olympics to rubber-stamp anyone.

No-one doubts that Hopkins or Zaha Hadid was involved in the Games and they feature in all the awards. But there are unsung heroes I’m sure who will benefit from this and I’d certainly like to know about their performances.

The industry is changing all the time and you don’t know where new thinking and new technologies are going to come from. I was impressed with the public space and by the buildings both in terms of design and delivery. The long-term thinking that went into the Olympics was unique - it was brilliantly conceived.

The 2012 sponsor

John Barrow, senior principal, Populous

All of the architects, engineers and designers involved in the Olympics should be about to talk about their achievements. It’s also good that this process is licenced and registered as that brings some rigour into who claims what.

We’ve been offered the chance to join the licence scheme and we will just to make sure we don’t encounter any problems. As a sponsor, we had the right to talk about our projects anyway so we are grateful now that there is no controversy - we were even being painted as the bad guys at one point.

Sponsorship was a big step for us - we wanted to show real commitment to the Olympics as a company. We think it’s been beneficial - we’ve won a whole series of projects in Russia; a lot of work on the 2014 Winter Olympics and a lot of stadiums for the 2018 World Cup.

The contractor

Jason Millett, chief operating officer for major programmes and infrastructure, Mace (Millett was also CEO of Olympic delivery partner CLM)

We’re pleased to see the ban lifted - it’s a chance for all the firms to get some credit and win some business. You used to get a number of smaller companies, such as one which made recycled decking material for the Olympics, who were really frustrated because they couldn’t show that experience on their marketing material.

It’s firms like that which I think can really benefit and that’s important because there were firms like that all over the country who contributed.

There are a lot of clients in the UK and internationally who want to learn the lessons of London 2012. As well as sports work, it certainly applies to infrastructure clients such as Network Rail, the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority and EDF.

But for me, the bigger deal is that we have demonstrated to the world that we can do these things.

Supplier Recognition Scheme: How does it work?

In the BOA’s London offices, a small team is already busy dealing with hundreds of applications from 2012 companies eager to tell their stories. All firms which supplied goods and services to the ODA, Locog or Lend Lease (which acted on behalf of the ODA on the Olympic Village) can apply for a licence giving them a package of Olympic recognition rights until the end of 2015. This will transform the information they are able to put out on their websites, at trade shows and for awards and, crucially, in procurement and tender processes.

There is a checking process to ensure firms are bone fide 2012 suppliers and that they are given the correct official designation, which could be as specific as “electrical labour supplier to the 2012 velodrome”. While this can take a maximum of three to four weeks, Barbara Gill, BOA’s supplier recognition project manager, says applying is quick and straightforward.

“The feedback we’ve been getting back from firms has been great,” she says. “The form only takes 15-20 minutes to complete so it’s not like a typical tender document.”

To apply, visit: ww.srs2012.com

.jpg)

No comments yet