How can we ensure that high-density housing brings a variety of types and tenures – and doesn’t ignore the need for family homes? By Paul Wellings-Longmore

Families are at the core of our national housing policy. The break-up of the traditional family, which has led to greater demand for smaller and more affordable households, is often cited as a major contributor to the current housing shortfall.

There is often a contest between the developers and planners regarding housing demand, with the percentage of family housing being a pawn in the negotiating process. Housebuilders frequently contend that the market demand is for one- or two-bedroom apartments, while local authorities argue the need for a greater mix. Over the past 15 years there has been a dramatic rise in the proportion of flats constructed in the UK – from 15% to 45% of total new homes built.

High-density housing

Innovative forms of high-density, affordable housing are often advocated as one response to concerns over housing shortages. The London Plan and planning authorities, however, don’t always agree on what constitutes high-density housing. In order to maximise the potential of sites, government guidance and the London Plan (policy 4B.3) generally promote greater densities than local authorities anticipate. For the purposes of this article 350 habitable rooms/ha or above (net site area) is considered to be high density.

Family housing

Most local councils define family accommodation as four or more habitable rooms providing three or more bedrooms, and require a reasonable mix of housing types; both family and non-family to create genuine communities.

Many require about a third of housing units to be family-sized, and some ask for a small percentage to have five or more habitable rooms. Local authorities also recognise that while family accommodation is not well suited to very busy or noisy environments, it is often unavoidable.

Family housing poses a number of challenges, not least the economics of building larger dwellings. Families and communities have been broken up because people are unable to afford to live in areas where they were brought up. With property prices escalating, developers will often find a readier market for smaller units that appeal to young couples anxious to get onto the housing ladder.

Planning policy statement 3

PPS3 (Housing) was published in November 2006 and came into practice on 1 April 2007. It seeks to ensure that sufficient housing is provided to meet local demand and that the mix and type of housing addresses the needs of the community. It is billed by the government as a “step change” and comes in response to economist Kate Barker’s review of housing supply.

It is too soon to evaluate the impact of PPS3 on housing development but its aim of providing design-led mixed neighbourhoods, with a range of dwelling sizes, backed up by a requirement for local authorities to supply evidence-based housing assessments, is welcome.

What constitutes a family unit?

In high-density schemes, with people densities of around 350-450 per hectare or more, family units are under pressure in favour of smaller units and those that do not require space hungry external room. Conversions of existing homes have led to a loss of family housing and increased pressure on the limited supply of on-street car parking.

While national policy requires a mix of housing, there is often no local guidance outlining the preferred residential mix or the percentage required. A recent argument from a developer even suggested that given the growth of single-parent households, one- and two-bedroom flats should constitute family housing.

This argument cuts no ice with the local planners, but is not so far-fetched given that Section 106 agreements often class two-bedroom flats as “family units” for purposes of education contributions.

E Design

For the designer, the biggest challenge is to reconcile the spatial demands of family housing with high density. As living standards have risen, so has the demand for more private and public space, play areas and parking.

Family units need access to communal amenities and recreational space that can cater for the needs of children – with play areas and informal play space. There is particular pressure for family dwellings to be at ground level, where habitable accommodation competes with other functions such as entrances, refuse storage, services plant and other such facilities.

Specific requirements that need to be addressed are:

- Family units require higher levels of car parking than smaller households

- Cycle parking for families often means one space for each child rather than one per dwelling

- Families need gardens

- We need to go beyond Housing Corporation scheme development standard space levels and consider the additional storage that all families need

Solutions

For too long, there has been pressure to pack dwellings closer, shoe-horn infill onto brownfield sites and work down to (rather than up from) minimum space standards. This is all despite housing quality indicators or scheme development standards.

There have been too many schemes that lack genuine variety of types and tenures. We have a duty to provide better quality in both public and private sectors, and this means being generous about the provision of larger units and space standards. If better design and space depress residential land values, this in itself may be a good thing.

From a practical perspective, our experience suggests that it is better to separate family housing from other types of accommodation to deal more effectively with its special requirements, especially when dealing with the social rented sector.

This must be handled sensitively to ensure that quality standards are applied across all tenures – to be “tenure blind” to use the current jargon. At Goldhawk Road, west London, on the site of the former Queen Charlotte’s Hospital, Hunter & Partners has created a range of houses and flats that take great care to integrate family housing with other types of accommodation. Here, family accommodation takes a traditional form as terraced housing that holds the street frontage, with private back gardens protected from traffic noise.

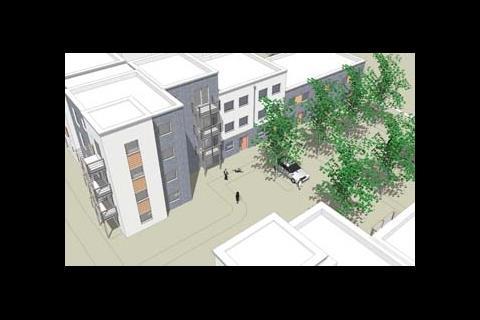

Housing with gardens is usually the most satisfactory arrangement, but is not the only option. Space restrictions may make other forms more appropriate. Flats on upper floors are not desirable; however Hunter & Partners has also proved the creative use of stacked maisonettes at Twickenham Road – a major development for English Partnerships in Isleworth, West London (see page 39). The arrangement has the potential to provide gardens for the ground floor dwellings and private roof terraces for upper level units, above street level.

Balconies are often discounted by local authorities when calculating the quantity of usable amenity space. Early discussion with the local planning authority on how they intend to calculate external space is essential, including issues such as keeping amenity space away from busy or noisy roads. Balconies and terraces are also an effective way of providing external private space where site restrictions do not allow adequate gardens.

Care, however, should be taken with the design of larger balconies to complement and assist in the housing management function to ensure that they are not misused - becoming nothing more than external utility rooms, repositories for bicycles and broken refrigerators. Solid balustrades are a safer option than clear glazing.

Conclusion

High-density sites need to meet the twin challenges of rising housing demand against falling land supply. This needs to be achieved while avoiding the mistakes of the past where families were isolated in multi-storey developments above ground. It falls to those who develop housing, whether in the public or private sectors, to find ways of creating high-density sites that match modern day family housing needs.

Source

RegenerateLive

Postscript

Paul Wellings-Longmore is design director of architect Hunter & Partners

No comments yet