Housing is shaping up to be a key election battleground for Labour, and new shadow minister Emma Reynolds will be leading the charge. She tells Joey Gardiner why she is not afraid to take on the big housebuilders. Photography by Astrid Kogler

Emma Reynolds is excited. Labour’s new shadow housing minister, replacing the more sober veteran campaigner Jack Dromey, seems to be doing her best, at 36, to inject a touch of youthful enthusiasm into the role. “I LOVE it!” she beams, when asked about the move from her last job as shadow Europe minister. “I mean I’m passionate about Europe too but the agenda was so dominated by the right [wing], and anti-Europeans. It was very hard to be heard. But every issue impacts upon housing.”

Her promotion in Labour leader Ed Miliband’s October reshuffle means that less than four years after entering parliament - she was elected MP for Wolverhampton North East in 2010 - she already has a seat at the shadow cabinet. “It is such a privilege to have a seat at the top table,” she says with appealing modesty. “My rule is to only speak when I’ve really got something to say.”

But if she has a real enthusiasm for her new job - her father was an architect who designed and built his own home - it is probably fair to say she has less enthusiasm for major housebuilders. We meet just days after she has given her first keynote speech in which she bemoaned the “broken gearstick” in the housebuilding industry that seems to make it unable to respond to the scale of demand for new homes. Before Christmas, her boss Miliband went further, outlining his “use it or lose it” policy on land banking and accusing listed builders such as Taylor Wimpey, Berkeley and Barratt of hoarding land while seeing profits rise 557% on the back of record low build rates.

So with housebuilders clearly not flavour of the month at Labour HQ, the question for Reynolds is firstly whether the housing industry is about to be lined up alongside the big energy firms as the next target in Miliband’s campaign to identify what he sees as unproductive “predatory” businesses. But it is also whether this fresh face in Westminster has the similarly fresh policy ideas required to bring other players into the market.

Work in progress

Sixteen months away from the next general election, there are certainly plenty of new policies buzzing around Miliband’s team. Former New Labour troubleshooter Sir Michael Lyons has started a review of housing policy for the party that will focus on areas such as reform of the land market, a generation of new towns and a “right to grow” for councils with housing expansion plans. He will submit his final report in September. This review has already produced some proposals, such as forcing developers to register land ownership publicly and options designed to break the veil of secrecy over land speculation.

But in most respects Labour housing policy is nevertheless a work in progress. So if you’re reading this piece hoping for an answer as to whether Labour will extend or abolish the government’s Help to Buy scheme, Reynolds is going to disappoint you. Likewise, if you want to know whether a future Labour government would reverse the 60% cut in funding for affordable housing introduced by the coalition, and instead embark on a major programme of affordable housebuilding, you’re not about to get an answer. “We certainly disagreed with the coalition’s 60% cut in affordable housing funding. But am I in a position to tell you what we would do if we’re elected in 2015? No, I’m not,” she admits. You get the picture.

We certainly disagreed with the coalition’s 60% cut in affordable housing funding. But am I in a position to tell you what we would do if we’re elected in 2015? No, I’m not

Yet it is already starting to become clear what Reynolds’ focus will be. A self-confessed social democrat, she says she believes in not just equality of opportunity, but also that government should aim to make society more equal overall. Her experience of living in a council flat for three years after her parents split up has made her a passionate advocate of social housing, and her experience as a constituency MP - in the town she grew up in - has put her on a mission to raise standards in the private rented sector in order to protect vulnerable tenants. In words that may alarm those seeking to see the growth of institutional investment in new-build private rent (which she also professes to support), she says: “I’m not afraid to say to you that we need to regulate it better. Someone said to me the other day, ‘wouldn’t that be a barrier to entry?’

I said actually I think that’d be a decent barrier to entry. Why shouldn’t landlords have to register? Why shouldn’t they have to meet basic standards? Why shouldn’t a local authority have the ability to prosecute them if they don’t meet those standards?”

Breaking the grip

Of course, her main role will be to work out how to increase the output of new homes. She doesn’t believe the counsels of despair that say politicians will never truly tackle this problem because the public are too invested in the value of their own homes to vote in favour of a solution, even one that benefits their own children.

Instead, Labour’s analysis is that the grip on supply of new homes by a small number of the main housebuilders is at the root of the failure to build enough homes in the UK. Her detailed knowledge of Europe means she is constantly looking to the continent for comparators: France, she says, builds three times as many homes with a similar population; Japan has double the population but 10 times the build rate. Much of this disparity, she feels, is down to the lack of small builders and self-builders in the UK. Whereas in the thirties the top 10 builders built just 6-7% of the UK’s new homes, now small builders (defined as building fewer than 500 homes per year) account for just one-third of completions. So are the big listed players misusing their position?

“We want a competitive and diverse market. Obviously big housebuilders have an essential role to play, but even in the good times we weren’t building enough homes to keep up with demand, and the truth is they do dominate the market here in the way they don’t dominate the market in other countries. The housing market isn’t working in the way that it should, in terms of delivering opportunities for young people and families to get on the housing ladder, [and] the role of politicians is to make markets work better.”

She avoids answering whether this dominant position should be enough to trigger a Competition Commission investigation, but continues: “We think there are fundamental structural problems with the land market, and we’ve asked Michael Lyons in his housing commission to set out some proposals as to how we will reform that land market. You could argue that the housebuilders in the market at the moment are simply responding to that [but] I’m not really arguing that. I do think there is a responsibility not to sit on land”

To that end, Labour has set out plans for a public register of land ownership and options.: “There clearly needs to be more transparency around land. We really don’t know how much speculation there actually is, and speculation is part of the problem.”

Reynolds says that Labour will make councils include a certain proportion of small sites in their local plan housing land supply in order to benefit small and custom-builders. Just don’t ask her what proportion of land will be small sites.

Housebuilders of course deny Labour charges of land-banking. But they shouldn’t be under any illusions about the party’s will to make changes to tackle what it sees as a big problem. Under Labour’s “use it or lose it” policy, local authorities will be able to charge rising fees to housebuilders that are found to be “hoarding” land, with beefed-up compulsory purchase powers to be brought in as a final sanction if developers don’t comply.

We want a competitive and diverse market. The major housebuilders have an essential role, but they haven’t built enough homes to meet demand

“If the major players do the right thing and build houses, that’s fine. If they’re sitting on land, then there will be penalties. If they don’t think it’s a problem, then they’ve got nothing to fear, have they?” However, Reynolds’ certainty starts to waver when asked if developers whose sites are no longer viable because of economic changes would be penalised, or developers of large sites where only one phase was being built at a time. “The local authority will have to make a decision as to when it’s actually going on.”

Housebuilders have hit out at the plan as economically illiterate, and turned the tables on the public sector to justify all of its use of development land. But Reynolds isn’t having that: “I don’t think it is the issue. It’s a defensive position to say ‘if you released all the public sector land, we wouldn’t have a problem.’ Well, I don’t think that’s a solution. Some public sector land is not in places where people want to live. So let’s be realistic about what we’re talking about here.”

But despite criticising the major housebuilders, Reynolds avoids the temptation to brand them - according to Miliband’s conference catchphrase - as either “predators” or “producers”. Certainly, her focus on small builders and self- and custom-builders is adding to the feeling that Labour under Miliband is increasingly looking like a party - unlike Blair’s New Labour - wary of big business, and conversely keen to champion small and local enterprises. It remains to be seen whether the detail of Lyons’ review will do enough to assuage concerns the party is heading in an anti-business direction, and, more importantly, whether they’ll actually work to increase house production.

This story was originally published online with a poll. This has now closed.

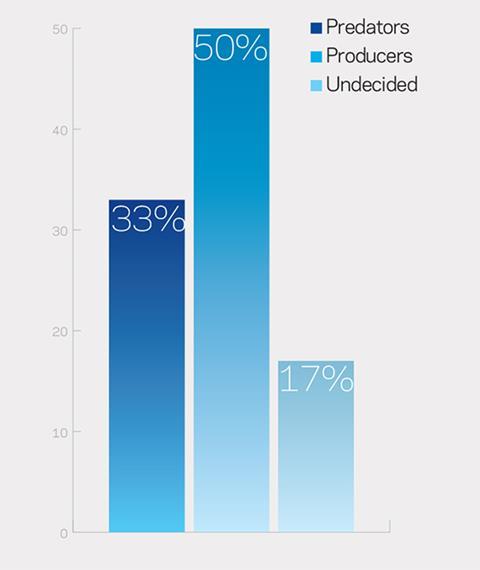

We asked you if, after Ed Miliband’s attack on “predatory” businesses, do you think major housebuilders are “predators” or “producers”?

Here’s how you voted:

Emma Reynolds

Political insider Reynolds’ career to date has been dominated by Europe, first as political adviser to former foreign secretary Robin Cook, then later as chair of the Party of European Socialists. Her only sojourn in the private sector was to work for public affairs consultant Cogitamus before standing in the 2010 election. Some in the sector may worry that her passions appear to be around social justice rather than the drier stuff of improving economic output, but she is refreshingly plain speaking and more than bright enough to know she would - in power - largely be judged on whether she can get more homes built.

The Lyons Review

Sir Michael Lyons, a former chair of the BBC Trust, was tasked by Ed Miliband in September last year to come up with a programme to meet Labour’s target of constructing 200,000 homes a year in England by 2020. An expert panel including the likes of Barratt chief executive Mark Clare and National Housing Federation chief executive David Orr is advising. It is focused on five areas:

- Unlocking the land market

- Public and private investment in new homes

- New towns and garden cities

- Giving councils a “right to grow”

- How to share the benefits of development with local communities.

The Alan Cherry debate

The funding and provision of private and affordable housing is set to be discussed at a half day conference hosted by Countryside Properties in conjunction with Building magazine on 6 February, at the RICS, 12 Great George Street, London.

Secretary of state Eric Pickles will be the keynote speaker with other contributors including David Lunts, executive director of housing at the GLA, Christine Whitehead, from the Cambridge Centre for Housing and Planning Research, and Brendan Sarsfield, chief executive at housing association Family Mosaic.

Countryside will also announce the winner of its annual Alan Cherry Placemaking Award.

No comments yet