Despite this market perception sustainability is rising up the agenda for many developers. Not least in driving this change was the introduction of the revamped Part L1 of the Building Regulations, which has forced architects and developers to look long and hard at the design of their schemes. When it came into effect in April 2002 the measures put in place to improve fabric insulation and glazing performance, as well as the need to consider solar shading and air leakage led many to re-evaluate their traditional approach.

"The 2002 Part L was a big driver for change," says Ashley Bateson, associate with Fulcrum Consulting. "Developers and architects realise the implications of having to increase the thermal requirements of the building envelope. A lot of the housing projects that we have been working on involve trading off improvements in the solid walls to deal with the fact that contemporary architects, especially of luxury housing, want large areas of glazing."

While the impact of Part L1 has been significant there are other factors influencing design. Changes in Planning Policy Guidance encouraging developers to consider higher density new build housing are having an impact, as are Unitary Development Plans (UDPs) incorporating requirements for sustainable development, and decisions taken at local political level. Merton Borough Council is one body taking a lead. In its recently revised UDP it stipulates that all projects over 1000 m2 have to consider 10% of their energy supply coming from renewables. In a similar vein the Mayor of London has published his draft energy strategy (soon to be finalised), which supports the use of renewables and the doubling of chp in the capital, principally through developing community heating. Although this might not have a statutory basis, much of its aims can be influenced through the statutory planning framework.

On the horizon also is the EU directive on the energy performance of buildings, which requires alternative systems such as district heating and chp to be considered on buildings with a useful floor area exceeding 1000 m2. While this doesn't directly apply to domestic properties it could well become a factor encouraging the adoption of community energy schemes.

Market forces

Despite this legislation, without the market demand private developers are understandably cool when it comes to adopting overtly sustainable designs. "As a practice we're environmentalists," says Brian Mark of Fulcrum Consulting. "But we try and keep it quiet now because it gets in the way. If you say to a housing developer, 'here are the environmental benefits aren't they wonderful' they quite rightly say: 'we are in the business of selling homes, our purchasing public is indifferent to them'. And so predicating high level environmental design on the understanding that people value it is just not true."

Fulcrum has been working on a number of housing schemes with various developers. "We present the above the line advantages and the below the line advantages," says Mark. Above the line includes issues such as reducing costs and, say in the case of installing a chp system, getting an outside company to take responsibility for the capital investment and operation and maintenance. Below the line advantages are areas such as corporate social responsibility and CO2 reduction that, while a client might value, are secondary to their primary objectives but could be viewed as putting them ahead of their competitors.

Sustainable design can be approached in two directions. Reducing loads through the building design, such as envelope performance, construction materials, daylighting and water consumption, as well as infrastructure and master planning. "We are doing the two together," says Mark. "Providing green infrastructure and also constructing buildings which need far less energy to operate."

In infrastructure terms a mixed-use development can provide big advantages. On a daily timescale housing has a large hot water demand in the morning with a further peak in the evening, while commercial has its peak in the day. Overlaying the two can provide a steady load, making a better economic case for a community energy system. The economic case for on-site generation is less clear-cut. While banks of pvs and wind turbines are a means of raising awareness of renewables, on a purely economic basis they often fall short. With most urban regeneration occurring in built up areas it can be difficult to maximise the expenditure on a turbine. However, the answer might lie by looking beyond the physical boundaries of the project. When it comes to offsetting a development's CO2 emissions Mark argues that it is better for a developer to invest profits in a remote wind farm. "This means you make the profit and then invest it in an asset, which is growing and pays dividends. If you took that money and invested it on wind turbines on your building it's a depreciating asset and it doesn't yield much in terms of electricity. It's obviously the way to go in terms of economic evaluation," he says.

One scheme Fulcrum is currently involved with is value engineering a zero energy development project to be commercially viable on all development parameters. The brief is exemplary in terms of sustainability but it has to be achieved at a cost that feeds directly into a market sale and achieves normal percentage profit. But while private developers concentrate on the bottom line, other factors come into play for housing associations. As part of the government's bid to promote sustainability housing corporations will often lend more money if the development is 'green'. A number of large grant funds are available for this technology, such as the Community Heating fund and Clear Skies, which are only applicable for not for profit developers. This gives housing associations access to funds which can cover up to 50% of design and development costs and 40% of the capital cost, making a sustainable design well worth pursuing. To be eligible, designers often have to demonstrate that the project would not be financially viable without the grant in place.

Westway Beacons

Fulcrum is currently working on a scheme with Threshold Housing Association. The 100% affordable housing development comprises of five buildings totalling 8500 m2 in West London. As well as working on aspects of building envelope performance, construction materials and daylighting to produce a low energy, low CO2 output development, if the scheme gets the green light it will be the first aquifer thermal energy store (ATES) project in the UK.

ATES finds its natural home in community heating (and potentially cooling) systems. The client first saw the system operating in Holland, where it is commonly used as a retro-fit solution to 'green up' 70s concrete tower blocks and is established to the point that the Dutch equivalent of the Environment Agency has set up rules and guidelines regulating such systems. Fulcrum has now formed a partnership with IF Technology with the aim of introducing similar systems to the UK.

ATES is similar in many respects to ground thermal energy storage, the difference being that heat collected during the summer can be stored in the aquifer and retrieved for use in winter. Heat can be delivered to the dwellings by means of lthw, generated by a water to water heat pump connected the aquifer store. Summer heat collection can be enhanced by the use of solar collectors or by removing heat from the building (say using a run around coil in an ahu), thereby effectively cooling the building as part of the summer heat collection strategy. Unlike passive annual storage heat buildings1 the process can be carried out remote from the building.

"This is interseasonal heat storage, so we are interested in energy use per year, not per day," explains Mark. "In Holland they use this system to try and capture within a master plan served by the pipes, buildings such that the amount of cooling needed equals the amount of heating." This offers the opportunity for excess heat during the summer to be dumped into the store and used during the heating season for residential premises or other net heat demands.

The Westway Beacon scheme only captures housing, making it an overall heat needer because of the domestic hot water demand. If it could be linked to surrounding commercial buildings the solar collectors could be eliminated, and with it a major chunk of the capital cost.

While the aquifer thermal energy store is an additional cost, in large enough numbers it could potentially be cost neutral. The 128 dwellings at Westway Beacons is probably less than half the number required and with the scheme only now going out for its first contractor quotes it's still early days understanding the capital cost. On the plus side it employs conventional technology and construction techniques, and the volume of energy on tap means there is no need to insulate the distribution pipework, allowing low cost plastic pipe to suffice. The Dutch however have achieved economic paybacks of three to five years.

Guilt-free cooling

Cooling is a by-product of the technology used on the Westway Beacons scheme and an area of increasing interest to many designers and developers. While Part L of the Building Regulations has been improved, changes have yet to be made to Part F covering ventilation. "One of the impacts of low air infiltration and very high levels of insulation, particularly when looking at modular lightweight construction, is the building can solar oven," says Mark. This together with the public perception of rising summer temperatures means that inherently low environmental impact cooling systems can be a real selling point for developers. A bonus Fulcrum terms 'Guilt free cooling' While cooling was a spin-off for Westway Beacons, mechanical ventilation and filtration was a planning stipulation imposed by the proximity of the traffic flow predictions. The lack of standards and regulations for indoor air quality in housing means mechanical ventilation it is still rare in UK housing. However Environmental health Officers do have powers under the Environmental Health Act to force designers into using it. Traffic generated pollution and noise within central Liverpool is so great that planners have said all dwellings must have full mechanical ventilation systems with filtration. This can have positive outcome. "If you've got mechanical ventilation you do have capital cost value, but there is no doubt it's lower energy than natural ventilation due to the heat recovery aspect, which is not possible with natural ventilation," says Mark.

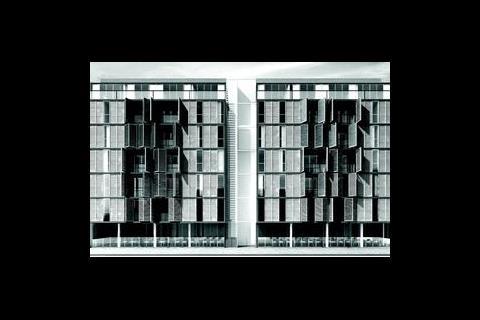

Fulcrum is also using whole house mechanical ventilation on other schemes. Urban Splash's Burton Place project in Manchester incorporates internal kitchens and bathrooms. The client was convinced of the energy saving advantages of using a central fan system but introducing make-up air has been tackled in separate ways for different phases of the scheme. Initially the architect picked a good quality Danish window system that introduces air through the trickle vents at a very low additional cost to the window frame. A similar solution wasn't possible for the second phase as the architects wanted full height glazing and couldn't design a trickle vent system that they were aesthetically happy with. Instead air is supplied at low velocity in the bedrooms and lounges, giving the benefit of heat recovery. "They've both got central 24 hour extract systems while one has heat recovery with supply air, so it will be interesting to monitor these two to see how they compare," says Bateson.

Air is extracted via the cooker hoods. These have been specified from Sweden, where they have been using the system for over 20 years, but unlike conventional hoods there is no fan just a filter and small damper that can be opened further if a local boost is required. In such cases a pressure sensor sends a signal to the ahu which responds to the increase in demand by picking up speed via an inverter control. The result is a system barely noticeable to occupants with low fan consumption.

Up to the mark

Another incentive for house builders to consider sustainability in their designs is EcoHomes, the residential version of BRE's Environmental Assessment Methodology. "Housing corporations that give grants will sometimes more favourably help a housing association if they can say they've got a 'good' EcoHomes rating." The current system for new, converted or renovated houses and apartments uses ratings of pass, good, very good and excellent. Making the jump from pass to very good can be prohibitive on cost grounds. However, single increments over several years, which may initially result in a cost rise of around 5%, gives developers a chance to manage the costs and explore the best deals. "Even a private housing developer we work with employed us just to look at what differences it made to the design for a pass, good, very good. They were doing it because they thought it would help sell the house," adds Bateson.

Changes to the Building Regulations and planning requirements, as well as the grants on offer, mean housing is becoming an increasing area of work for many building services consultants, and for some it stretches beyond building design into areas of master planning. With 85% of housing being built by commercial developers it is clear where the focus for sustainable development lies. But as Ashley Bateson says: "You need clients who are prepared to stick their necks out and not be risk averse, because it's all to easy to say it won't work". But when you've got an enthusiastic client such as the Threshold Housing Association, you can have a truly pioneering scheme.

Source

Building Sustainable Design

No comments yet