The firm’s president and CEO took the helm at a turbulent time for the country and for contractors. She tells Chloe McCulloch about her leadership style, her rejigged executive team and how industry and government can deliver more with less if they work together. Portrait photography by Tom Campbell

Katy Dowding is not where she should be. Our interview was supposed to take place at Skanska UK’s South Molton site, just down the road from Bond Street Tube station, where it has broken ground on the £140m first phase of the mixed-use scheme for Grosvenor and Mitsui Fudosan UK. But there has been a change of plan.

Dowding emerges from a meeting room at the tier one contractor’s City office at 51 Moorgate, extending a hand covered by a medical wrist support and walking slightly gingerly. The PR had warned she had hurt her knee, and it turns out a skiing accident has resulted in a severed cruciate ligament and a possible broken bone in her hand. Walking does not hurt too much, it is just that uneven surfaces are not recommended, so site visits are a no-no.

Still, it must have been very painful at the time? “Let’s just say, I think I said something to the effect of ‘gosh that hurts’ but with stronger words,” she deadpans with a grimace.

Dowding, 55, likes to be on the move. A big part of being the CEO and president of Skanska UK is obviously travelling around the country visiting project teams on site. “It’s my favourite thing, getting out on site,” she says, clearly annoyed about not being able to get to two new sites – South Molton and 7 Millbank, the former British American Tobacco HQ in Westminster – because of her knee. “I will find a way, I will get to the projects, even if not on the actual site.”

Another frustration is that her injury put paid to competing in a mini-triathlon, which involves a 400m swim, 20km bike ride and a 5km run. Instead this month she will be undergoing an operation and is then looking at up to a year for a full recovery. “I’m booked in for next April’s triathlon,” she states, her smile widening at her own optimism and determination.

It’s my favourite thing, getting out on site. I will find a way, I will get to the projects even if not on the actual site

Dowding has 36 years of working in construction under her belt, 22 of which have been at Skanska UK. In the top job running the UK’s £1.3bn business for the past two years – the only woman CEO of a tier one contractor in the UK at the moment – it has been a period of considerable geopolitical upheaval in which UK business sentiment has been buffeted by a general election and grim autumn Budget.

Relaxed and clearly at ease in the job, Dowding talks frankly about how she sees prospects for the UK market, the challenges for tier one contractors trying to increase margins and her ambitions for Skanska UK’s own performance now that it has rejigged its executive team to coincide with its new plan for the next three-year business cycle. She acknowledges that, in recent years, the business has shrunk in response to fewer market opportunities in certain sectors, which explains the cautious approach the company is taking to the challenging commercial offices market.

She also has plenty to say about the new Labour government’s measures that fit with its stated pro-growth agenda – and the ones that do not. Positive noises from ministers about investing in infrastructure are welcome, but she is clear that a transparent pipeline of actual projects – and some real momentum in attracting private sector investors to pay for it – would be even better.

Continuity and change

A quantity surveyor by background, when Dowding took over the top job from her predecessor Gregor Craig when he retired in April 2023, she was presented as the continuity boss. Having joined Skanska two decades previously – the same year in fact as Craig himself, who also arrived from Tarmac, where Dowding started out and which by then was part of the Carillion empire – she had earned her stripes in various operational and then commercial roles.

Her jobs included five years as managing director of the facilities management (FM) arm, where she learnt a lot about the value of long-term client relationships: “With FM, we were signing 10-20 year projects. It’s like a marriage, and you’re going to fall out with each other, but you’ve got to sort it out and work together properly.”

Having stepped up to president and CEO after a time as deputy vice-president, one of her first challenges that summer was the UK business being forced to restate its 2022 profit figures because of underestimated costs on some contracts. Later that year she had to make “efficiencies” involving some job losses of what was described as “back office staff” as well as seeing the departure of a couple of executives due to “broader challenging market conditions”.

So, why was pre-tax profit for 2022 revised down to £24m from the previously stated figure of £55m? Dowding says the vast majority of those additional costs related to a legacy job, while Skanska was also dealing with a couple of jobs that “just didn’t deliver, finished a bit late”, although she says those issues would not have materially impacted on the profit figures.

The market’s tough, and there’s not quite as many of the right opportunities out there at the moment

She will not be drawn on which contract caused the real pain, but says it was signed about 14 years ago and represents the kind of deal the contractor does not enter into nowadays in terms of risk profile, but also the nature of the construction work which was “completely different to anything we do now”.

Dowding is clear that Skanska UK is not a revenue-chasing business and takes a “profit approach”, acknowledging that in revenue terms it is smaller than it has been historically. Explaining the lower turnover, she says: “The market’s tough, and there’s not quite as many of the right opportunities out there at the moment, so we contract. If the right opportunities come, then we expand again.”

In January this year, Dowding rejigged her executive team, which is now made up of seven people, creating a new role for Jo Mortensen to oversee technology, sustainability and innovation – aspects that had been dispersed lower down the hierarchy of the organisation but which are now elevated to ensure the firm is “digitally fit for the future”.

In addition to Mortensen, whom she brought over from Norway where he had been in a similar role for about five years, there is Harvey Francis, chief people officer, and Meliha Duymaz, chief finance officer who joined in 2022 from Network Rail. Plus there are now three exec roles focused on the operational side: Terry Muckian runs the building business, Andrew English oversees infrastructure and High Speed 2, while Adam McDonald looks after building services and Cementation, its piling business, and also doubles up as the chief commercial officer.

This structure, Dowding says, means the executive team is now closer to operations, having stripped out a layer of management between them and the project teams in the building and infrastructure businesses. The chief commercial officer role is to drive profitability by focusing on “making sure we get the right deals, the right balance of risk and reward”.

The strength of this senior team is crucial, Dowding says. Since becoming CEO she has come to understand just how “wide your radar needs to be” and so creating a high trust culture where her team can bring different perspectives and the most up to date information that may challenge a position she holds is vital.

“At this level, there’s a lot more operating in what is termed the ‘grey space’,” she says. “You are making decisions with lots of unknowns. You’ve got to come to the best decision.”

What does she think of the traditional contractor command and control style of leadership? “I’m sure it works for some, I think this is definitely harder and takes longer, but I think you end up with better decisions.”

Katy Dowding’s CV

2023 Skanska UK president and CEO, succeeding Gregor Craig

2017-23 Executive vice-president with responsibility for Skanska UK’s building and building services businesses

2012-17 Managing director, Skanska Facilities Services

2009-12 Business development director, then operations director, Skanska Facilities Services

2007-09 Business development director, Skanska Utilities North

2004-06 Studied for a masters degree in interdisciplinary management of projects, sponsored by Skanska

2003 Joined Skanska in an operational role working on the Ministry of Defence refurbishment of its main office in London, MOD Whitehall, then moving on to the redevelopment of both Barts and The Royal London hospitals

1989 Joined Tarmac as a trainee QS

UK construction markets

On Skanska UK’s current level of profitability, Dowding says bluntly that it “is not what we want it to be” – its 2023 pre-tax profit, the latest available, was £27.3m on turnover of £1.33bn. Asked if she has an ideal profit margin in mind, she refuses to be drawn on an exact number but makes the more general point that all tier one contractors are trying to push margins up.

“If you look at the level of risk, if you’re operating only on 1% or 2%, the whole thing can get completely knocked out by one job. It’s too precarious,” she says.

In February this year the wider Skanska Group, headquartered in Stockholm, reported margins of 3.5% in its 2024 results, which showed turnover last year was up 13% to SEK177.2bn (£13.1bn). But the group pointed to the market worsening in the UK in its forecast for the year to come.

A particular challenge in the UK is the commercial offices sector, where Skanska UK has a strong reputation having built the Heron Tower and the Gherkin. But current market conditions have led to its so-called “two-two-two” strategy, whereby it will work at any one time on only two jobs at pre-contract stage, two on site and two close to completion.

Dowding says the strategy is all about managing risk. Skanska is not interested in the very transactional clients that enter the London market with one-off jobs. It wants long-term relationships with blue-chip clients, the likes of British Land and Landsec, with whom individual deals are done – such as the 1 Appold Street scheme at Broadgate for the former and the £250m Hill House job near Fleet Street for the latter.

She does not rule out changing the rule to “three-three-three”, but that would require more work to come from “the right” clients.

At a time when the office market is subdued, it makes sense to push ahead in other sectors. And Skanska is active in most other areas including rail, highways, data centres, water, energy, defence and healthcare – the company viewing the latter three as “buoyant”.

The firm is no stranger to high-profile public sector contracts, of course, being on the Skanska, Costain Strabag joint venture that is tunnelling to Euston, work that was put on hold by Rishi Sunak’s government in October 2023 and then revived a year later by Labour chancellor Rachel Reeves.

[HS2 has] only got so much money to spend in the year. So I think it’s incumbent on us to be as productive and as efficient as possible and handle the savings

Dowding says the JV is “driving towards Euston” but other elements within the scope of the “Euston approach” works are being rescheduled. This is all part of what Mark Wild, the new HS2 chief executive, has called a “fundamental reset” to get on top of costs.

Dowding thinks Wild’s intervention will not affect the eventual scope of the works, rather it is about the timings of certain elements – such as bridges – that will connect to Euston station because the station itself is not going to be ready any time soon. “If something doesn’t need doing this year, if [Wild] can put it off to next year, he’s going to have to do that, because he’s got to manage his in-year spend.”

While she can see the logic, she acknowledges the impact that delaying certain works will have on the supply chain, which also includes Skanska in the form of its piling business Cementation. “It’s a headache we could have done without, but I understand it,” she says.

“They’ve only got so much money to spend in the year. So I think it’s incumbent on us to be as productive and as efficient as possible and handle the savings, so that we can build as much as we can for what they can afford to spend.”

To that end she, along with Alex Vaughan at Costain and Simon Wild at Strabag, meet regularly with HS2’s boss and work together to find the answers to questions such as: “What can we pause? What can we accelerate? How can we do some something more cheaply?”

Infrastructure and the role of private finance

And Dowding has some suggestions for how the government as a client could help in the delivery of major infrastructure projects. For a start, it could do better at managing the pipeline of jobs, so that, rather than making speeches with vague promises of hundreds of projects to come at some point in the future, it could provide a proper list of specific projects that are actually ready to go to market.

Asked about recent positive messages conveyed in politicians’ announcements, she says simply: “It’s a long way from the podium to a shovel in the ground.” The Lower Thames Crossing, which got the green light last month, and on which Skanska is working on the southern section, is a good example having encountered numerous obstacles since it was first proposed 16 years ago. Now the £16bn project has got planning but, in project terms, it is still in the very early stages.

For one thing, the funding still has to be worked out, which could create some issues “if funders put conditions on the job, which then need to flow into our contract, we would have to thrash that out, but they might put none and we carry on”.

The industry does have an ally in government, she says, in the form of Darren Jones, second in command to Reeves at the Treasury and “very user friendly”. From her encounters with him when in opposition and overseeing the infrastructure advisory panel, and subsequently as he has set up the National Infrastructure and Service Transformation Authority (NISTA) “he properly listens”.

Most importantly, he sees it as part of NISTA’s role to take more time up front making sure projects are ready to go to market, that the funding has been signed off and procurement routes are agreed. Without this approach, or a specific list of projects, it is almost impossible for contractors to plan ahead because “we might be building roads, or we could be building offices, or we could be building railways.

“They might be in Yorkshire, but they might be in London, or they could be in the South. It’s very difficult to recruit for skills [or make] the right decisions.”

Jones and his influence at NISTA could be very useful in tackling some of these issues, but when it comes to this government coming up with the money for all the infrastructure it wants to build, there are still some question marks. Has Dowding seen any evidence that ministers are considering particular vehicles that would attract private investors to pay for projects, such as Euston station, which currently is in limbo awaiting a funding solution?

On finding money for Euston station she says diplomatically: “I think there is still a lot to sort out.” More generally on private finance models she thinks ministers are at the early stages of their thinking, having established that there is money they could attract but perhaps still uncertain as to how to make the financing work.

Government wants to build a load of stuff and there’s not enough money, so whatever it looks like, there’s got to be some form of PPP

Responding to Building’s Funding the Future series that is looking for creative financing solutions, she says that in her view private finance will have to play a role in the current government’s plans: “It’s basic economics. Government wants to build a load of stuff and there’s not enough money, so whatever it looks like, there’s got to be some form of PPP. Obviously they won’t say PFI, but some sort of private finance.”

She says she has been involved in industry conversations with the government and one idea is gaining traction: the mutual investment model, or MIM, that has been used in Wales. This is where the local authority becomes a member of the special purpose vehicle (SPV) by either putting in land or taking an equity stake.

Skanska has some experience here, having historically been an investor as well as a builder. Skanska Integrated Projects used to invest in SPVs, and only withdrew from that five or so years ago, while the wider Skanska Group continues to invest globally.

Skanska UK does not currently have any plans to get back into the investment side of UK projects but Dowding does advise the government to think carefully about how attractive it can make deals for global investors: “They might think, ‘This is quite a good deal in the UK’. It might be, but it might be nowhere near as good as an investment opportunity is Sweden, or Norway or the US.”

The state of UK contracting

For a government that claims to be pro-growth, April’s national insurance contribution rise has been a blow to business confidence across the sector. Dowding does not say how much it has added to her wage bill, but “it’s a significant portion of profit” and has meant the company has had to “switch off some planned investments”.

She says she is sympathetic to government ministers and their task of having to balance the books, but “what irritated me most about the NIC rise was it was flagged that it was coming, but the threshold [change] wasn’t flagged to us.” And, if taxes are to go up, businesses also want to know there will be a drive for “efficiency in government spending”.

What irritated me most about the NIC rise was it was flagged that it was coming, but the threshold [change] wasn’t flagged to us

Industry for its part has its efficiency critics. Dowding is on the government-backed Productivity Taskforce, and as a commissioner on our own Building the Future Commission in 2023 she spoke about the need for the industry to up its productivity levels. But she says technology is now making a big difference.

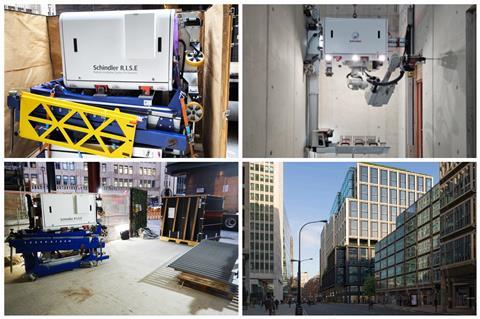

There are the shiny, new innovations, of course, such as the lift shaft-building robot developed by Schindler that Skanska is using at 150 Victoria Street, known as RISE which stands for robotic installation system for elevators (you can read more about it in our article here).

But Dowding seems just as interested in the types of productivity gains that can be overlooked because they come under the heading: “boring process efficiency”. One example is in navigating the complexity of contracts.

“Specification can sit in many different places,” she says. “Technology can extract all your contract obligations. It can link those to people’s site diaries and action plans so you make sure you’re fulfilling all your contract obligations.”

She also feels that AI’s potential to make efficiency gains at a company and project level is now being realised because different platforms can interconnect, whereas before advances were being made in isolation. Skanska launched its own proprietary AI platform, called Sidekick, last year enabling staff to retrieve valuable information about projects across the group in a highly secure platform that guards against data leaks.

Dowding on ….

… Being lucky

Quizzing was one of Dowding’s early side hustles. In her 20s and early 30s she made it on to game shows such as Jim Davidson’s Big Break, Bruce Forsyth’s Didn’t They Do Well, as well as Bullseye, Catchphrase and Get Stuffed.

Apart from the glory making it onto the TV, she also won a cool £40,000 in prize money over a decade or so – tax free of course.

In fact her TV career started even earlier as a child extra who appeared on shows such as Worzel Gummidge (three times), and she was partial to a bit of am-dram in her youth. So, was she never tempted into the world of showbiz as a full time vocation?

No, apparently the young Dowding decided there was no money in it. “I was always focused on making money,” she admits, holding down jobs as a teenager at the local stables, doing bar work and even setting up as an Avon lady for a while.

She only stumbled into quantity surveying because a friend’s description of it as requiring a combination of maths with something “practical and hands on” appealed (her dad was a maths teacher and her mum ran a catering business). It was 1989 and, in the days before Google, so she flicked through the Yellow Pages, found an ad for Tarmac and wrote a letter “basically saying, ‘would you like to sponsor me to do a degree?’.”

She got the interview, persuaded her first employer to take her on and her first day working in construction was on day-release at college.

She thinks of herself as a lucky person, despite being born on 13 March at 13:13 and in the 13th year of her parents’ marriage – “unlucky for some, but not me”.

… EDI and the workplace

Men who are CEOs do not tend to get asked what it feels like to be a male leader, but over time Dowding has got used to others holding her up as female role model. Other women in the sector have pushed back at the title, pointing out that being expected to not only be great at your job but also further the cause of women more generally can feel like an extra burden.

Dowding does not feel any burden, more a sense of responsibility: “There’s a feeling of not wanting to let the side down. That comes back to me being competitive with myself. I don’t want to fail at this role for me.

On behalf of all the women out there, I don’t want to be the one that mucks it up. If I fail, it would be because I’m just not a very good CEO. It’s not because I’m a woman

“But I also think, on behalf of all the women out there, I don’t want to be the one that mucks it up. Because, if I fail, it would be because I’m just not a very good CEO. It’s not because I’m a woman, but it would be seen as ‘the woman that failed’.

“You can think about the flip side: if I make a stonking success of this, people will say, ‘it’s because she’s a brilliant woman’. And I’ll take that as well.”

So, where does she stand on flexible working – which often benefits women – and the recent push back on EDI more generally, which has seen many employers mandating five days back in the office?

“We don’t mandate. We don’t believe in mandating, but what we do say is ‘you need to prioritise the needs of the business, the project and your team before your personal [needs]’.”

Skanska UK moved to its Watford HQ in 2022. It has a fully flexible layout as well as a canteen, gym and decent coffee. She says she thinks the company’s approach means that just as many people are now back in the office since covid as at those contractors that decided to mandate.

Skanska’s in-house “digital academy” has a rolling AI training programme for staff – 50 have completed it so far – to make sure their skills keep up with the pace of change.

Dowding says she gets annoyed by the “lazy trope” that contractors are either inefficient or greedy. Construction costs have gone up, she says, partly because contractors have far more environmental compliance and planning hurdles than ever before.

The higher costs compared with other countries of delivering infrastructure may also be down to the standards we build to in the UK: “If you go down to the Metro in France, it’s spray line concrete, it’s not finished. It’s really basic. There’s no additional safety screens on the platform edges. I love the Elizabeth Line – it’s beautiful. You’ve got your copper molding, wonderful [safety] screens. We apply a higher level of engineering, higher level finishes and specifications.”

So, looking ahead to future big infrastructure projects, we have to decide as a country what we want to pay for and what we don’t: “We just have to choose to cut our cloth.”

The state of the public finances is a reality but not a reason to be defeatist, according to Dowding. She believes the government does have levers it can pull, particularly in terms of working more efficiently with industry, getting infrastructure jobs properly ready for market, which will come back to the role of NISTA in planning ahead.

“Too often we start on site when we haven’t got half the consenting or half the commissions or diversions.” The key then is “being prepared to wait, and then to start jobs at the right time”. A combination of patience and planning is her route to getting where we want to be.

Building’s Funding the Future campaign seeks to examine fresh ways of attracting and using finance to boost construction projects at a time of constrained public finances.

It will examine options for public-private partnerships that can draw on private capital to pay for large infrastructure projects, schools, prisons, hospitals and housing.

It will also look at existing models for private and public funding and examine how these can be optimised to ensure funding is efficiently spent and leads to more shovels in the ground as Keir Starmer looks to construction to boost flagging economic growth.

Over the next few months we will share learning, consult with industry and collect ideas from readers. This will culminate in a special report to be published at our Building the Future Live Conference in London on 2 October - click here to book your tickets now.

To share your ideas of new funding models, email carl.brown@assemblemediagroup.co.uk. To find the campaign on social media follow #Buildingfundfuture.

No comments yet