After a tough few years, things are looking up for housebuilders, judging from their profit figures. So why are we still in the middle of a housing crisis?

A quick glance at the profit figures of the major housebuilders in the last year and you’d think everything was rosy in the housing sector. Pre-tax profits are up 160% across the eight biggest listed builders, the mortgage market is slowly easing, and the legacy of debts racked up pre-credit crunch have been largely sloughed off. Experts have been pleasantly surprised by the resilience of a market for new homes that some had predicted was headed for sustained decline, with prices in London at least now marginally above their pre-credit crunch peak.

But last week government data showed that far from riding on this upturn, home starts are actually falling - and falling sharply. To be precise, they fell by 11% in the last three months. As the figures came out a joint report by three of the most influential housing organisations - the social landlord association the National Housing Federation (NHF), housing professional body the Chartered Institute of Housing (CIH), and homelessness charity Shelter - panned the government’s record, saying its policies were failing in five out of 10 areas.

The reality is the coalition’s first two years in office have been the worst two years for housebuilding since 1946, despite the fact housing minister Grant Shapps has said the government should be judged on whether it can increase housebuilding levels. The report described this record as “very troubling,” and the latest data suggests 2012 might end up being even worse. To fight this, the government has pumped in £570m to the Get Britain Building initiative, set up a mortgage indemnity scheme underwritten by £1bn of government guarantees, and raced to identify surplus public land for new homes. So, given all this political attention and the stable outlook described in the results posted by the listed builders, what on earth is going on?

The easiest answer to this question is to blame the cuts in funding for affordable housing. There’s no doubt these have been dramatic, with the communities department losing 60% of its affordable housing budget in the 2010 Spending Review.

Figures from the Homes and Communities Agency, published last autumn, underlined the significance of the cut, which entails an entirely new way of funding “affordable” homes. They showed a fall of 97% in the number of starts in the six months to September 2011, with just 454 begun, compared to over 13,000 in the same period in 2010. However, the figures were more an indication that the new funding system was taking time to bed down. With £1.7bn of new development contracts signed since, work has picked up quickly, meaning that for the last 12 months starts are actually down by just 21% on the year before. As Abigail Davies, assistant director of policy at the CIH, admits, the new funding system, although controversial politically, should see the numbers of affordable homes built rise.

She says: “The contracts are now signed, and while it’s a fact there was a drop-off in output, there’ll be a pick-up relatively soon as the contracts have to be delivered in 18 months.”

Furthermore, with affordable homes counting for just over a fifth of new homes started, this drop is not actually the most significant part of the story. The biggest part of the problem is with the private sector developers that build the majority of new homes, but that cut starts by 8% in the first quarter of the year.

Following the 2008 credit crunch, many of the UK’s biggest housebuilders spent a good 18 months on life support propped up, ironically, by banks that decided they were “too big to fail”. However, this year’s eurozone crisis finds them in very different shape: their debts have been slashed, they have raised equity from the stock markets to fund new developments and much of the unprofitable land left on their books from before the credit crunch has been developed.

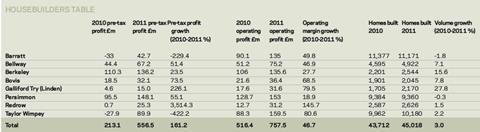

Indeed, you could almost say it was a time of plenty for them. Building’s analysis of the eight largest listed housebuilders (see table below) shows that in their most recent full year results, overall pre-tax profits were up 161% on the year before - a total of £556m of clear profit. However, at the same time the number of homes they built was up by just 3% - with two of the largest, Barratt Homes and Persimmon, actually building fewer than the year before.

Housebuilding is a notoriously cyclical industry. But previous recoveries in profits have led to a recovery in sales volume - the idea being to make as much as possible from a positive market by building as many homes as the market will sustain. Some, notably Bovis Homes and Redrow, are pursuing this strategy today. But for others, something very different is happening. Rather than invest their cash in opening new sites and building more homes, major players such as Persimmon, Berkeley Homes and, to an extent, Linden Homes, are choosing to give billions of pounds back to shareholders. Mike Killoran, finance director at Persimmon, explains the thinking: “If we invested another £1bn in housebuilding, it would only dilute our return in the current market. We can’t push volume artificially. We have a duty to generate the highest possible return for our shareholders. We need to give the capital market reassurance that we’re working for their benefit.”

The move is designed to counter the traditionally low valuations given to housebuilders by the stock market. But Robin Hardy, an analyst at Peel Hunt, says Persimmon’s move, and others like it, are historically unprecedented. “In the past the whole sector always acted the same way. Now some are taking a view of the risk of taking on debt to finance expansion, and realise they don’t have to grow in scale to create a good stock market valuation.”

In layman’s terms, the builders have realised their share prices will do better if they promise years of good dividends, rather than volume expansion. A higher share price then enables them to raise cash more easily when needed. But in a wider sense, Hardy says, controlling supply helps keep house prices up. “The housebuilders have no interest in increasing volume,” argues Hardy. “They know that greater volume creates a less attractive pricing environment.”

Effects on the wider economy

All of this makes perfect sense for each of the housebuilders themselves, but adds up to a big problem for the economy as a whole - growth in housebuilding could have gone a long way to reversing the 3% decline in the construction output in the first quarter of this year, had the builders followed their traditional strategy. With just 109,000 homes built in 2011, the rate of build is less than half the estimated 240,000 homes per annum demand. The CIH’s Davies says: “There’s quite a feeling that private developers build to return money to their shareholders. And there’s a growing clamour for developers to do more in return for the support of the government.”

The Home Builders’ Federation says the issue is not quite this simple, arguing that continuing mortgage constraint, site viability problems and the burden of regulation play their part in explaining slow volume recovery. Stewart Baseley, executive chair of the HBF says: “Housebuilders’ profits were severely damaged by the recession and housing market downturn. While some progress has been made in rebuilding margins, there is more work to do. This process has to be seen against a background of enormous economic uncertainty which is causing understandable caution.”

So why don’t other smaller builders, or new ventures step in to fill the demand gap? Unfortunately, for smaller players, things don’t look so rosy. Without the ability to raise money on the stock market, smaller builders are dependent on bank lending to get the cash to start construction - cash which is not forthcoming. Far from contemplating expansion, many are still struggling to survive. “The downturn is much more severe among smaller builders, and the most important issue is a lack of bank finance,” says Roger Humber, strategic policy adviser at the House Builders’ Association (HBA).

The government’s interventions, trumpeted in last autumn’s housing strategy, have so far failed to make much impact. As indicated by Davies, developers have taken the government’s £570m Get Britain Building fund to unlock specific stalled sites, but not made any wider move to up building rates overall. Meanwhile, an end-to-end review of the planning system, which may still ultimately make builders’ lives easier, has thus far caused mainly paralysis in transition, a situation exacerbated by deep cuts in many local authority planning departments. “The planning system is effectively on strike,” Humber says.

In addition the government-backed mortgage guarantee scheme, NewBuy, hailed by prime minister David Cameron as a “vital boost to the housing market” at its March launch, is yet to prove itself. Lenders have set the rates for the mortgages so high that just five homes are reported to have been sold so far, though the HBF claims that 400 homes are in the process of selling.

While Bovis chief executive David Ritchie is “quite pleased” with progress, Humber alleges that smaller builders have been largely prevented from taking part by the labyrinthine bureaucracy of the process. “For the vast majority of people it clearly isn’t working,” he says.

Section 106 - the flexible friend

For social landlords already struggling with the new social housing funding regime a further problem has arisen. Councils are increasingly taking advantage of new flexibilities regarding the amount of social housing expected on development sites, delivered via the Section 106 process. While housing minister Grant Shapps gave councils these freedoms in order to encourage development on stalled sites, housing associations claim developers are trying to take advantage of it to improve profit margins, and cash-strapped local authorities are using it as an opportunity to fund other pet projects. Brendan Sarsfield, the chief executive of social housing association Family Mosaic, says developers are using “lies, damned lies and statistics” to re-negotiate agreements (see below).

Davies says: “This is the top concern currently coming to me from social landlords. Most people say the bottom has fallen out of it [the market for homes via section 106 agreements].”

For the sake of the economy a host of new entrants seem to be required to really Get Britain Building - hence the government’s interest in attracting pension funds to invest in homes for rent. However, the difficulty of financing development for all but the listed giants, means this is unlikely for the foreseeable future. The government may have to intervene more directly if it is serious about creating a record it is willing to be judged on.

The problems with planning gain

Brendan Sarsfield, chief executive of housing association Family Mosaic

Historically planning gain has delivered around 45% of social housing. Until the credit crunch and the initial drop of confidence in the property market, developers, councils and social housing providers knew how the game was played around planning gain.

The rules did need reviewing and I was one of those that supported greater flexibility in Section 106 agreements. During hard times I wanted development (and some social housing) rather than no development. I believe this flexibility is now being exploited by most sides to the detriment of new social housing.

Developers in London and some other areas are agreeing deals with planners which are reducing Section 106 commitments even though the sales market is strong. I don’t know how they are convincing planners that schemes are less viable today and cannot afford the social housing elements

of their schemes, but they are. Lies, damned lies and statistics, I assume.

There are examples in London of planners agreeing zero social housing, and many other compromises in between. It is becoming the norm not the exception. Just talk to planning consultants about the growth in commissions to go back and renegotiate deals on sites that already have planning consents.

It is important that developers make profits, but some are now making record profits. Has the flexibility gone too far? We need more transparency around the compromises agreed.

Councils are also taking cash from planning deals for their own purposes (not just the GLA’s Crossrail levy) rather than providing social housing. Their planning principles appear to be compromised totally when councils are selling their own land. Zero social housing on a site means a larger capital receipt for the council.

What is desperately needed is a rethink on how a flexible system can work positively for social housing and developers. In a time of scarce government funding, we must fight to keep the planning gain for its original purpose.

1 Readers' comment