Keir Starmer wants his government’s response to the tragedy to mark a defining moment in the safety and quality of housing in the UK. Is the industry prepared for it? Tom Lowe and Daniel Gayne report

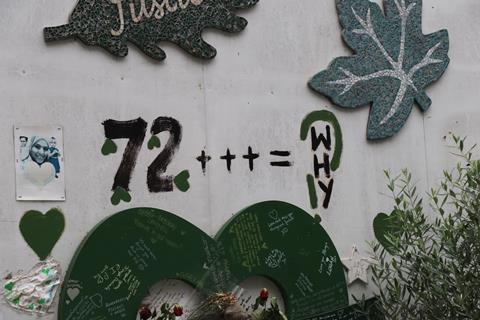

Two weeks before the publication of the Grenfell Inquiry’s final report, Keir Starmer was taken on a tour of the burned-out shell of the tower in west London where 72 people lost their lives in 2017.

He spoke of his experience in his address to parliament on the day the report was published last week. “As I walked down that narrow staircase from the 23rd floor, and looked at walls burned by 1,000-degree heat, I got a sense of how utterly, utterly terrifying it must have been,” the prime minister said.

“It left me with a profound and very personal determination to make the legacy of Grenfell Tower one of the defining changes to our country that I want to make as prime minister. We will deliver a generational shift in the safety and quality of housing for everyone in this country.”

For anyone in the construction industry wondering how seriously the government will take the inquiry’s 58 recommendations, this gives a pretty clear indication. By making his speech personal, Starmer left himself very little room for rowing back or justifying half-measures. He is bent on his premiership delivering that “generational shift”.

The question now, for both the government and the construction industry, is how literally the recommendations should be implemented. The 1,700-page report, the product of seven years of hearings, has proposed sweeping changes to the regulation of building safety on top of the reforms which the industry has already seen since the fire.

One of the most striking recommendations is for the government to “draw together under a single regulator all the functions relating to the construction industry”. This would be an independent body headed by a single person and reporting to a single secretary of state.

Impact of a new and expanded regulator

The problem is that we already have a Building Safety Regulator, one which has taken several years to establish and with powers that the sector has barely had a chance to adapt to. Already, industry experts are anxious about the disruption which further regulatory changes could bring.

“It feels like an awful amount of work has gone into building a new regulatory system and the inquiry has basically said, ‘not good enough, needs to be bigger and more expensive’,” one senior figure at a major contractor admitted. “The appetite for change around responding to new measures will be limited, I think.”

Simon Tolson, senior partner at law firm Fenwick Elliott, worries that firms would be unsettled by having to face yet another new set of rules. “I think it’s quite disturbing for the industry, having gone through the Building Safety Act and a lot of the regulation under the statutory instruments that the act brought in over the last couple of years, and getting adjusted to that, and then finding that this inquiry report yesterday is making suggestions.”

The reality is the industry is still playing catch-up with what is on the statute books

David Savage, partner at law firm Charles Russell Speechlys

Others see the logic behind creating a centralised regulator but question whether it could lead to unintended consequences. “A lot of progress has been made,” says Construction Products Association chief executive Peter Caplehorn. “So it’s not as if we just started work changing the industry from this week.

“But what I am conscious of is that taking on board some of the recommendations – for instance, bringing things together under one regulator, could potentially delay or at least slow down progress. And I think that’s something that we need to reflect on.”

David Savage, partner at law firm Charles Russell Speechlys, welcomes the proposal but fears the industry could go into a “period of perpetual revolution” if the changes are not introduced gradually. “The reality is the industry is still playing catch-up with what is on the statute books.”

The inquiry report criticises the regulatory arrangements in the years leading up to the fire for having become “too complex and fragmented”. At the time of the fire, building regulations and statutory guidance was under the remit of the Department for Communities and Local Government, product regulation was overseen by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy and fire and rescue services were the responsibility of the Home Office.

Meanwhile, building control was shared between local authorities and approved inspectors acting as commercial organisations, testing and certification of products was carried out by bodies which were also commercial organisations, and law enforcement was carried out by Trading Standards. “In our view, this degree of fragmentation was a recipe for inefficiency and an obstacle to effective regulation,” the report says.

But, despite the establishment of the Building Safety Regulator (BSR), introduced through the Building Safety Act 2022, the inquiry found that responsibility for these different parts of the industry “remains dispersed”. While the BSR sits within the Department of Work and Pensions, the construction products regulator is within the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government and fire risk assessment is within the Home Office.

There will be staff and functions to transfer, senior teams to recruit, cultures to be aligned, and governance arrangements to be agreed

Matthew Gill, programme director for public bodies at the Institute for Government

Under the report’s proposals, the centralised regulator would be responsible for the entire industry including regulation of construction products, testing and certifying materials, oversight of building control and licensing of contractors to work on higher risk buildings (HRBs), which are currently defined as those over 18m in height which contain at least two dwellings.

It would also monitor the operation of building regulations and statutory guidance, carry out research on fire safety, issue accreditation of fire risk assessors and share information with fire and rescue services.

A chief construction adviser – someone with a “good working knowledge and practical experience of the construction industry” – would be appointed by the secretary of state. This role would come with a significant budget and staff to provide advice on matters including the government’s work on building regulations and other issues affecting the industry more generally.

These would be big changes to the current arrangements and would likely take some time to implement. Matthew Gill, programme director for public bodies at the Institute for Government, warns that successfully merging disparate organisations and teams often takes years. “There will be staff and functions to transfer, senior teams to recruit, cultures to be aligned, and governance arrangements to be agreed,” he says.

“It has to be clear who remains responsible for what, and staff need to be kept actively engaged with the rationale, as well as the practicalities, of the change they are being asked to bring about. This could be a particular challenge in this case, given that the existing Building Safety Regulator was established so recently.”

The set-up of any new regulator would also likely go through consultations to ensure a consensus on day one, both among politicians and its staff. It would also probably require new primary legislation to transfer responsibilities to the new body, potentially reopening a Pandora’s Box as the bill makes its way through parliament.

But there are also clear benefits to implementing this change. Institute for Government researcher Sophie Metcalfe says teams in different departments are often siloed even when working towards the same goals, in this case construction regulation. “There’s often no incentive for cross-government working,” she says. “There’s little reward for finding your counterparts in other departments and coming together regularly as a group. That’s something you have to be very proactive to do.

“So you get people thinking in quite a siloed way about how to improve recommendations in their individual area, but you don’t get them talking to other departments about how it’s happening there.”

This dispersal of responsibilities across different bodies is exactly what the inquiry criticised in its assessment of building safety regulation before the Grenfell fire.

More on the Grenfell Inquiry Phase 2 report

Product manufacturers come out fighting after Grenfell Inquiry’s damning verdict

What the Phase 2 report said about consultants and contractors

Grenfell Inquiry Phase 2 report: all our coverage in one place

Decades of central government failure led to Grenfell tragedy, says inquiry

Then there is the issue of which department the new regulator would report to. It is worth noting that not everybody believes it should report to a secretary of state at all. Rudi Klein, the former chief executive of the Specialist Engineering Contractors’ Group, fears the influence of vested interests. He would prefer a completely independent body reporting to parliament in the same way that the National Audit Office reports to the Public Accounts Committee. “Otherwise we’re going to end up with government smothering, or attempting to smother, actions that need to be taken. That’s the record of government, isn’t it?”

One industry expert sees the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government as the “natural home” of the new body, but warns that the reorganisation would be a “huge undertaking” if done in the way the inquiry recommends. This is partly because the existing BSR sits within the Health and Safety Executive, which reports to the Department of Work and Pensions. Moving it to a different department would mean stripping the regulator out of its governance context and shoehorning it into a new one.

Others are speculating about how this disruption could be minimised. PRP partner Andrew Mellor believes the current BSR should take on the other duties, as setting up an entirely new body could be “quite wasteful”.

Transferring some staff, like the Home Office team which is currently in charge of fire risk assessment, to the new regulator would be “quite a simple move”, Mellor says.

Oversight of building control and building regulations already sits within the existing regulator, which means it would have to absorb other proposed functions including the responsibility for product testing and a register for contractors licensed to work on HRBs. “I can see them being able to do all of that; the question is, where does the resource come from?” Mellor asks.

A question of resources

This concern has been raised by many experts who have spoken to Building criticising a lack of resources at the current regulator. Klein says the government would need to be “prepared to shell out and put in the resources, because, when you think about it, we are talking about reforming industry practices which go back around 150 years and haven’t changed”.

Savage says the political structure around construction has not been appropriate given its significance as a sector in many different ways, “probably since the Nick Raynsford era”, referring to the former Labour minister of state for housing and planning under Tony Blair.

One recommendation which could constitute a significant expansion of the government’s oversight of the industry could be the proposed licensing scheme for principal contractors working on HRBs. This could take “a bit of time to set up”, according to Mellor.

As it would sit outside current legislation, it would also require new primary legislation and the consultation, drafting and refining that comes with that. “It would not be a swift process,” says Blake Morgan senior associate Natalie Taylor, adding that, while it would be unlikely to take the five years it took to get the BSR up and running, it would still be a case of “years rather than months”.

But it is also one of the recommendations that could prove most onerous for the industry. While building owners are likely to welcome a change that would demystify the process of identifying a competent contractor, contractors may be faced with specific requirements and costs to become licensed.

“The detail of the scheme will be vital,” Taylor says. “If contractors aren’t willing to become licensed to undertake works on higher-risk buildings, this could mean even fewer fish in an already small pond.” This could cause further delays to vital cladding remediation work, but it could also lead to developers abandoning HRB projects or building much taller to ensure schemes remain viable.

Part of this will depend on the insurance market and whether it will be possible – or financially viable – to obtain professional indemnity insurance for directors signing personal undertakings that all reasonable care has been taken to make the building safe. “Fewer firms in the market risks increased costs, further delays, and would ultimately impact those still living in unsafe buildings,” Taylor adds.

To complicate matters further, the report also recommends an urgent review of the definition of an HRB. Criticising the current classification as “essentially arbitrary in nature”, it suggests a more relevant definition would include the nature of the building’s use and likely presence of vulnerable people for whom evacuation in the event of a fire might be difficult.

Inquiry timeline

14 June, 2017 In the early hours, fire breaks out at the 24-storey Grenfell Tower in west London and burns for 60 hours. Ultimately 72 people will die as a result.

28 June, 2017 Retired judge Sir Martin Moore-Bick appointed to lead a public inquiry.

28 July, 2017 Government announces review into building regulations, to be led by Dame Judith Hackitt.

19 Sept, 2017 Met Police says criminal investigation will widened, with individual charges to be considered alongside corporate manslaughter.

17 May, 2018 Hackitt report releases findings.

21 May, 2018 Grenfell Inquiry begins.

Sept 2018 Government bans use of combustible cladding on all new residential buildings above 18m, including schools and hospitals.

30 Oct, 2019 Report on phase one of inquiry published.

11 Mar, 2020 Then chancellor Rishi Sunak, creates £1bn fund to remove flammable cladding.

19 Jan, 2021 Government promises to set up new regulator to ensure safety of building materials.

10 Feb, 2021 Housing secretary Robert Jenrick announces £3.5bn package to pay for removal of unsafe cladding.

27 Oct, 2021 Government decides to charge property developers to raise £5bn to remove unsafe cladding.

7 Jan, 2022 Jenrick’s successor Michael Gove says flat owners in buildings taller than 11 metres will not have to pay for removal of dangerous cladding.

27 Jan, 2022 Grenfell Tower Inquiry enters phase two.

26 Aug, 2024 Fire breaks out at block of flats in Dagenham, which was undergoing work to remove unsafe cladding.

3 Sep, 2024 Media given advance sight of final report in a three-hour lock-in in west London.

4 Sep, 2024 (11am) Final Grenfell Inquiry report published. Sir Martin Moore-Bick makes statement.

4 Sep, 2024 (11.45am) Campaign group Grenfell United issues statement from steps of inquiry building in west London.

Sep 4, 2024 (12pm) Keir Starmer addresses parliament and commits to blocking firms blamed in inquiry from all government contracts.

It also calls for the profession of fire engineer to become recognised with a title and function protected by law. The report highlights that this role does not currently denote any formal qualification, adding: “Not all those who profess to be fire engineers are capable of performing that role competently and the complexity of the subject matter is not well understood.”

It recommends the establishment of an independent body to regulate the profession, define the standards required for membership, maintain a register of members and regulate their conduct. It also tells the government to take “urgent steps” to increase the number of places on high-quality, masters level courses in fire engineering accredited by the regulator.

A huge undertaking

All this has landed on the desk of a government that has promised to build 1.5 million homes over the next five years, a huge undertaking that equates to the previous government’s never-achieved target to build 300,000 homes a year. Regardless of Starmer’s personal commitment to changing the industry in response to the Grenfell fire, implementing the recommendations will have to be balanced with every other government pledge.

The prime minister has said the government will provide its response to the report within six months, and has in the meantime committed to a “system-wide” reform of the construction products regulatory regime in order to take the inquiry’s findings into account.

Caplehorn believes Starmer’s eyes are best set on the end goal. “While I understand that we need to recognise and deal with the problems that have come out in the past, we’ve also got to be realistic and focus a bit on how we really resolve the needs of the future,” he concludes.

No comments yet