For many youngsters, a career in construction is a closed door. Luckily, The Prince’s Trust’s holds a handy bunch of keys…

The first thing Harj Sangha from The Prince’s Trust did to help Simon Greenall start his career in construction was to give him a book of food vouchers. Before this, Simon, 19, thought that getting up at 4am to a breakfast of beer was nothing unusual and he was often too drunk to write his own name. The notion of finding a job was never going to cross his mind and yet, as he would prove in a matter of months, here was a young man with the potential to get a job as a window fitter in Medway, Kent - an area crying out for tradesmen.

What Simon needed was intensive emotional support to break out of the rut he was in and help to overcome the practical barriers separating him from an industry that, according to ConstructionSkills, requires 88,000 new recruits every year. The Prince’s Trust’s Get into Construction course was able to help Simon just as it is helping hundreds of other 18-25-year-olds gain a foothold in employment. An intensive full-time, two-week course, the programme provides trainees with practical onsite training across a wide range of trades, including bricklaying, joinery and tiling. It enables young people to gain their CSCS (Construction Skills Certification Scheme) card - an essential qualification to finding work in the industry.

Last year 300 people graduated from 27 programmes, and the courses are now so popular they are heavily oversubscribed. Such high demand for the course suggests that traditional routes to employment such as job centres are just not suitable for everyone. As Harj Sangha, Get into Construction programme executive for Kent, says. ‘The biggest barrier facing a lot of these young people is their own low self-esteem and lack of any support network, perhaps because they have spent many years in care moving from one institution to the next. In the case of Simon, he had no parental support and no motivation - we needed to find a way to make him believe he could do something with his life.’

Get into Construction targets four groups; the long-term unemployed, educational underachievers, care leavers and ex-offenders. Youngsters are referred to the programme directors by a wide array of services including the probationary service, young offenders institutions and housing associations as well as employment agencies such as Connexions and job centres. Very few participants have any formal qualifications and for most, the CSCS card test will be the first exam they have ever had to undergo.

‘Our first challenge is to get young people “work ready”’, says Judith Gill, programme director for the North-east, ‘Before they start on the course we teach the basic importance of things like time-keeping and reliability. Many just don’t know what is expected of them in a work environment.’

As in Simon’s case, some trainees are also provided with counselling services and even with financial support in the form of vouchers so that they meet the basics of feeding themselves and getting themselves to the programme which is run at training centres across the UK provided by Carillion, The Trust’s main training partner. In small groups of around 10 and with two tutors on hand, each youngster is given lots of individual attention as they are given a flavour of the trades that interest them and prepare for ConstructionSkills’ health and safety test and the CSCS card test itself. After completing their course, youngsters are given support for six months to help them find a job - about 75% succeed in moving into work and training.

Careful consideration is given to the kind of employment best suited to the course’s graduates. ‘We try and think about what companies would best suit a graduate,’ says Sagha. ‘It is still the case that construction sites can be macho, blokey places and on the large sites people with low self-confidence get picked on. I’ve found that smaller family-run firms suit a person like Simon who needs that extra support.’

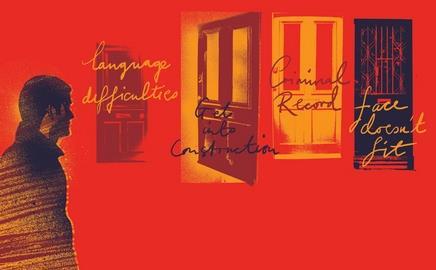

While the course organisers agree that low self-esteem is the most pervasive force holding youngsters back from achieving, all see cases where the young person wants to get a job but cannot because of a criminal record, language difficulties - or even just because of the way they look.

Abul Hussian, a 21-year-old immigrant from Bangladesh, applied for a place on the course after having spent time in prison for drugs offences. He had failed to get a job through an agency or job centre and believed that his history was putting off employers. The Prince’s Trust helped him gain his CSCS card and, armed with this evidence of his commitment to working in construction, he was able to get a job as a labourer with a top housing developer.

Sangha says there is still a stigma attached to ex-offenders. ‘By going on the course, Abul proved that he was moving on, but it can be very hard for ex-offenders to get work because employers worry about how reliable they 4 4are and there is a general taboo about employing them. It’s a real problem because it means young people can be tempted to try to conceal their criminal record, but it always gets found out and then they look even worse for having lied.’ She adds, ‘Companies could be far more open-minded about taking on people from this group; it’s a real barrier.’

The Prince’s Trust’s Gill says her experience also bears out what a problem a criminal record can be. Of the 11 people who joined her course in August 2007, one was a young offender and two others had criminal backgrounds; the other 8 were unemployed. ‘From this one course, that’s 30% of participants with a criminal background, so it really is an issue. Yet these three individuals, along with the other seven [one dropped out] made it to the end of the course,’ she says. ‘Nine of the group, including the ex-offenders, went on to secure jobs. It goes to show that people do move on.’

Sangha has also dealt with young people who have been excluded from the industry because their ‘faces don’t fit’. ‘Some young people have trouble getting on because they are gay or they’ve got tattoos or body piercing and don’t look the part. Not everyone fits the Bob the Builder image of a construction worker.’ Sangha mentions the two homosexual women and one man with sexual identity issues she has supported through the course as examples of individuals who encountered discrimination in their quest to find work in the industry.

Money can also be a barrier to entering construction. Richard Garnett, Get into Construction manager for East England, says it is easy to overlook the fact that gaining a CSCS card costs about £60; that’s £17.99 to sit the test, £25 for the card and up to £20 for a revision book. ‘It’s not a lot of money, but to someone on £40 a week on job seeker’s allowance, it’s too much,’ he says. The Prince’s Trust covers these costs and provides each graduate with personal protective equipment so they have the boots, hard hat and high-visibility clothing required for work on site.

Another serious hurdle young people face in entering the industry is the general lack of training and apprenticeships on offer. Garnett says the young people he meets are often aware that there is a demand for tradesmen in construction, but they cannot access any training. ‘It’s the classic Catch 22; they are unskilled so can’t get work, but they can’t get even the most basic job because they have no site experience,’ he says. According to Garnett, the biggest contribution employers could make to open the industry up to new recruits would be to provide more unpaid work placements. He says: ‘Some companies don’t want to touch people who have no on site experience, but you’ve got to start somewhere.’

It’s a plea echoed by all the Get into Construction programme leaders. Judith Gill says she only runs three courses a year and wants to run more but she needs more companies to support the programme and provide trainees with the critical onsite experience.

The Prince’s Trust is working to boost the number of courses it offers to 40 next year and, with the help of employers, provide around 500 young people access the industry. Says Sangha: ‘We’re proving that the course is powerful - it changes people’s lives and gives the industry the new blood it needs.’

Harj Sangha, Get Into Construction programme executive, Kent

'The biggest barrier facing a lot of these young people is their own low self-esteem and lack of any support network, perhaps because they have spent many years in care moving from one institution to the next'

Judith Gill, Get Into Construction programme director for the North-east

‘Before they start on the course we teach the basic importance of things like time-keeping and reliability. Many just don’t know what is expected of them in a work environment’

Richard Garnett, Get Into Construction manager for East England

‘It’s the classic Catch 22; they are unskilled so can’t get work, but they can’t get even the most basic job because they have no site experience’

Why we need The Prince’s Trust

- One in five young people in Britain are not in work, education or training - more than 1.2m

- Youth unemployment costs the UK economy £10m a day in lost productivity, and £20m a week in benefits

- Helping young people into employment could potentially save us £90m a week

- Youth crime costs the UK £1bn every year

- Nearly two-thirds of young offenders are unemployed

- More than 9 out of 10 of those leaving prison enter unemployment.

- Last year more than 3,500 participants in Trust programmes were offenders or ex-offenders. Two thirds of them moved into employment, education or training

The Princes Trust - Building better lives

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Currently reading

Currently readingUnlocking construction

- 6

- 7

No comments yet