Building speaks to Colin Ross, the firm’s country director, who is not planning on going anywhere despite the threat from Russia

“To top it all, I tested positive for covid last Friday.” Colin Ross laughs at the events he currently finds himself in.

In charge of Gleeds’ Ukraine office for the past five months, he is speaking from the apartment in central Kyiv that he shares with Ira, his Ukrainian wife of 22 years.

“We’re facing a multitude of problems,” he goes on. “The Omicron variant is now arriving with us, there’s a shortage of materials, there’s price escalations, you have to make sure projects are running properly.

”We have the same problems as everyone else. It’s just we have this extra one, which has us thinking at times. Dealing with Russia is not the biggest problem for me.”

Born nearly 53 years ago in Oban on the west coast of Scotland, Ross is remarkably calm about the possibility of the country he calls home being invaded by its giant neighbour.

He first came to the Ukraine in 1997. “Two years later I was married. Christmas Eve, 1999.”

Despite his ties with the country, he admits that his grasp of Ukrainian is not what it should be. But most of the 15-strong Gleeds office, based in the middle of Kyiv, speak English, so he gets by.

He says he is more fluent in Russian, speaking a passable version of it. If there ever was an invasion, then, would it come in handy? “I could tell them [the Russian soldiers] which way is home.”

In the 25 years since he first arrived, he reckons he has spent 16 years in the country largely with Scottish consultant Thomas & Adamson on various jobs, latterly the clean-up of the Chernobyl nuclear reactor, close to the border with Belarus, which blew up one April day in 1986.

I have a life here, a business. We accept the risks but we have made plans to get out if we need to

Colin Ross, head of Gleeds’ Ukraine office

When T&A left Ukraine in 2019, Ross went back to London leaving his wife, who is from the city of Dnipro in the middle of the country, behind in Kyiv. There was some umming and ahing about whether to move back to London for good, but the pair decided that Kyiv was where they wanted to be.

The travel restrictions caused by covid-19 meant they were forced to spend more time apart than they wanted before Ross finally found his way back, leaving T&A after more than 20 years last October and joining Gleeds, where he is now general director for Ukraine.

He spoke to Building on Tuesday afternoon. The Americans had suggested that the following day [yesterday] would be when Russia’s President Putin would order the 130,000-plus troops amassed on three sides of Ukraine’s borders to flood in.

However the Russians say they have now pulled some troops back, suggesting a possible de-escalation of tensions. The Americans and NATO, who yesterday accused Russia of sending more troops to the border, are not convinced. The threat of invasion, then, remains very real.

Ross might be calm but he is not unconcerned. “Of course, I’m worried. I’ve got family, I love this country. It’s my home.

“I would hate to see it invaded by anybody. A decision to leave would be very difficult.”

But, while newspapers in the West ponder the calamity of another war in Europe, Ross says people in Ukraine and Kyiv, a city of three million people, are getting on with their daily lives as normal.

We are working with our team in the Ukraine to ensure they have all they need at this time

Richard Steer, Gleeds chairman

“It’s very much business as usual from a lifestyle point of view,” he says. “There are no queues at petrol stations, there are no shortages of toilet rolls or pasta. People aren’t panicking.”

But, as a reminder of the situation the country finds itself in, he adds: “I do know some who have got in extra shotgun cartridges.”

For now, Gleeds is also carrying on as normal. Its chairman Richard Steer says: “We are working with our team in the Ukraine to ensure they have all they need at this time but clearly it is a fast-moving situation and our primary aim is to ensure that everyone is safe and feels supported where necessary.

“Many of our colleagues have been working remotely but this has as much been determined by covid than any reaction to global events. Our team very much represent a business as usual approach in their day-to-day activities but naturally we are all following Foreign Office advice as appropriate.”

Gleeds is working on a range of projects in the country such as green energy schemes, industrial facilities, logistics work, IT jobs and projects for embassies.

Ross says: “None of the projects we are working on have stopped. Embassy work is slowing and I suspect some projects won’t get signed off at the moment, but nothing has stopped. That’s quite important.”

Handily, some might say, he lives two doors down from the British embassy in Kyiv. The embassy has opened up a consular service in Lviv in the west of Ukraine, less than 50 miles from the border with Poland.

But the Foreign Office has not moved out of the capital completely. “The ambassador is still there and some core staff,” he adds. “I can see that the Union Jack is still flying.”

The embassy set up a call last week with those UK citizens still in Ukraine, whether by choice or those unable to get back to the UK immediately because of hold-ups with visas. Ross has made the decision to stay.

It’s a good day’s drive to the border. I don’t have any jerry cans, I would have to get petrol on he way. It’s a risk

Colin Ross

“The advice is that all Britons should leave. I understand I am on my own in that sense and I’m happy taking that decision. I have a life here, a business. We accept the risks but we have made plans to get out if we need to.”

Some people have already gone, generally those with younger children or those who have been told to leave by their employer. “I don’t know any local who has left other than those with Western families,” Ross says.

Outside his apartment his car, a Mitsubishi Outlander, stands ready, complete with a full tank of petrol, in case he and Ira have to leave quickly to make the 500-mile trek west to the Polish border.

The car is borrowed from a neighbour who has been in the UK for the past few months. “It’s unlikely we would get a flight,” he says.

“It’s a good day’s drive to the border. I don’t have any jerry cans, I would have to get petrol on he way. It’s a risk.”

If there is a Russian invasion from Belarus in the north, less than three hours’ drive away, he says he would be off. “If they came from the south or the east, we would wait and see.”

Ross has packed a grab bag and will stuff some clothes into a suitcase at the last minute if needs be. His grab bag includes bank cards, credit cards, wedding certificate, wills, other paperwork and three types of currency – sterling, dollars and Ukrainian hryvnia.

“Take what you can carry if you can’t continue in a car,” he says. He realises that, if there is a full-scale invasion, he would have to leave his home behind.

“You’re not going to be able to take everything with you. That’s not pleasant but it’s not the end of the world. The only way to ensure you take everything is to up sticks now and leave – but, if you do that, you’re not planning on coming back.”

If it does, in his words, go “horribly wrong” he and Ira would get to Poland and wait and see. Their grown-up daughter, Veronika, works in Brussels so is safe.

“We might stay in a hotel in Poland and see what happens or continue back to the UK. We haven’t thought that far ahead. It’s about getting safe first.”

He knows that they would be able to get back to the UK eventually. “Local Ukrainians don’t have a choice. They would effectively become refugees.”

He says there are already millions of so-called IDPs in the country – internally displaced persons – because of the war in the east in the region around Donbas which has been going on since 2014.

His family in Scotland are in touch and his wife, who works for the EU in Kyiv, has family in Manchester, where he worked with T&A for some years. “We’re not staying here to be brave. They are worried but they know we are not stupid.”

He adds: “If we can live here and earn money here and we have our health, we will stay here. I love this country and the people.”

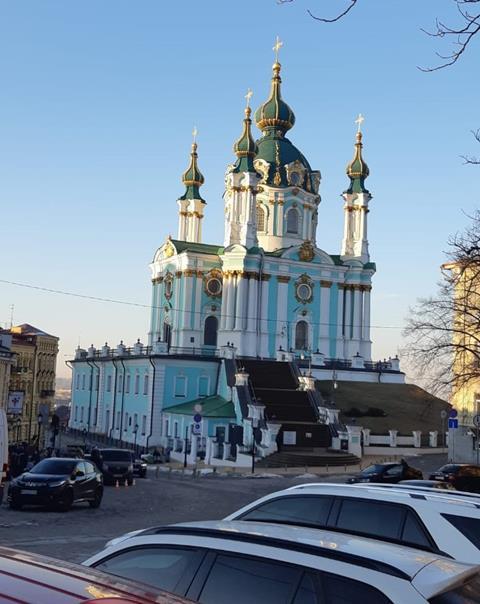

Within five minutes’ walk of his home are three of the city’s great Orthodox churches – St Andrew’s, built over six years in the mid-1700s; St Michael’s, built in the 1700s but demolished by the Soviets in the 1930s before being rebuilt and reopened in 1999; and St Sophia’s Cathedral where construction started in the 11th century.

“Kyiv is very green, it’s a beautiful city,” he adds. “It has cold winters and warm summers. The coldest I’ve known it is -37C and the warmest has been 45C. It’s usually low 30s from May to September. It’s got great restaurants, a café culture, very cosmopolitan.”

For now, the day after the supposed invasion, things are still calm. Yesterday was a day of unity in the country. Speaking yesterday afternoon, he says: “It feels a bit more patriotic if anything, but that’s about it.”

Ross knows of some locals who have signed up to the equivalent of the Ukrainian home guard and says some ex-pats are thinking about it as well. He feels sure his staff in Kyiv would volunteer too.

“If something happened, they would definitely defend their country.”

Before he returned to the capital last year, he ran the Manchester marathon. Two days later, he ran the one in Kyiv. Fatigue and a sore throat from covid aside, he seems in good nick.

Would he, then, ever sign up? “I’m more of a runner than a fighter,” he deadpans.

No comments yet