Explore the intricate restoration of the cathedral in Paris, where centuries-old craftsmanship meets contemporary design

Last weekend, the Notre Dame cathedral reopened its doors to the public for the first time since the devastating fire in 2019, offering a fresh look at its restored interior following five years of comprehensive conservation work. The reopening to the public, with events on 7 and 8 December, marked a significant milestone in the cathedral’s reconstruction and provided a chance to showcase the extensive repairs to its stonework, vaulting and timber roof.

The painstaking restoration was carried out using traditional craftsmanship such as hand-hewn oak beams for the roof alongside modern techniques including advanced digital modelling. This combined approach reflected a broader commitment to reviving traditional skills, with artisans employing time-honoured methods to restore the cathedral’s fabric.

The completed interior now features a bright, cream-coloured stone finish, achieved through a careful cleaning process intended to remove soot, pollution and fire damage. This involved applying a latex paste to the stone surfaces, which was then peeled off to reveal the original material.

While the restoration aims to return the cathedral’s interior to a more luminous state, some have expressed concern about the removal of the building’s natural patina, which many see as an integral part of its historic identity. As Liz Smith noted in her recent column for BD, Building’s sister title, “in an era when patina carries an age value that many appreciate as reflecting antiquity, the interior cleaning at Notre Dame could prove too much for hardcore conservationists”.

The reconstruction of the timber roof required techniques nearly lost to time. Carpenters used “green wood” to rebuild the 13th-century oak structure, with each beam hewn by hand.

These photographs offer a visual insight into the monumental restoration effort, capturing the finished interiors, while ongoing external and public realm work continues as part of the broader project set to complete in 2026.

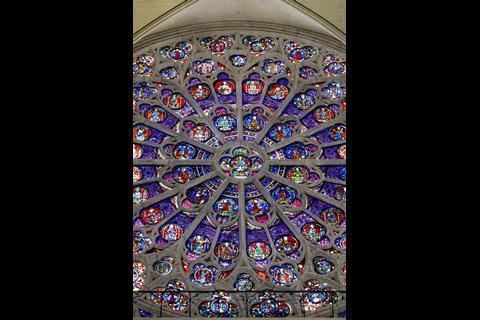

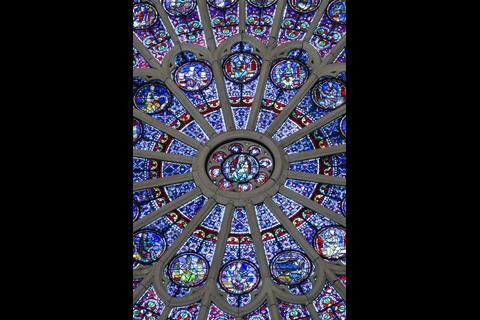

Windows and stained glass

Among the most significant features of the cathedral are its three rose windows, each a stunning example of Gothic craftsmanship. The south rose window, also known as the “midday rose,” measures almost 13 metres in diameter and depicts scenes from the Last Judgment, with Christ at the centre, surrounded by angels and saints. Its intricate design includes 84 panels spread over four circles, with symbolic numbers and references to biblical scenes.

The north rose window, largely intact with its original 13th-century glass, depicts Mary with the Christ Child, surrounded by kings and prophets, while the west rose window, the smallest and oldest, showcases the Madonna and Child in the centre, with rays symbolising the 12 tribes of Israel.

As the cathedral reopens, a controversy over replacing some of Viollet-le-Duc’s 19th-century stained glass with contemporary designs rumbles on. While the heritage committee overseeing the project unanimously rejected the idea, the proposal to introduce new stained glass, championed by President Macron, continues to provoke heated debate.

The ambulatory

The ambulatory of Notre Dame is designed as a walkway, allowing worshippers and visitors to move around the apse and nave. Unlike many cathedrals, Notre-Dame features a double ambulatory around the nave, defined by two rows of columns that form the side aisles.

When the cathedral was expanded in the 13th century, additional chapels were added along these side aisles. This distinctive arrangement of double aisles and a double ambulatory around the choir is a rare and significant feature in medieval church architecture.

Chapels

Notre Dame is surrounded by 29 chapels, many added during the 13th century, with those located around the choir known as “radiating chapels.” During the Middle Ages, wealthy families often built chapels to ensure ongoing prayers and services for deceased relatives.

These chapels were funded through foundations, with families offering annuities to chaplains in exchange for exclusive use of the space. As the 14th century progressed, the number of chapels and foundations grew.

Each chapel was typically adorned with an altar, statues, paintings and tombs, with some featuring elaborate wall decorations and relics of patron saints. Much of the cathedral’s chapel decoration was lost during the French Revolution, though some elements remain. Notable among these is the tomb of Simon Matifas de Bucy, bishop of Paris in the late 13th century. It is the only surviving painted 13th-century decoration.

Contemporary interventions

The new reliquary, designed by Sylvain Dubuisson, is inspired by the Crown of Thorns. Made of cedar wood, it takes the form of a large altarpiece. In the centre, a deep blue half-sphere surrounded by a golden halo creates a focal point for the Crown of Thorns when it is displayed. The reliquary also serves a more prosaic function, with a secure compartment concealed within its base for the safe housing of the relic when not on display.

The new liturgical furnishings in the restored cathedral have been designed by sculptor Guillaume Bardet. The five key elements – altar, cathedral and associated seats, ambo, tabernacle, and baptistery – are crafted from bronze.

Bardet’s choice of material was inspired by the power of the cleaned stone within the cathedral, which he described as a metal that manifests existence “without shouting” and “without over-showing”.

No comments yet