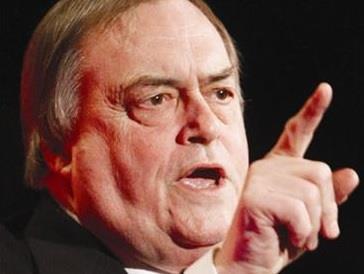

The former deputy prime minister, whose death was announced this morning, forced construction to realise that things couldn’t go on as they were

As the passing of John Prescott, who has died this morning aged 86, was announced by his family, it feels apt that 24 hours earlier the Health and Safety Executive published its latest annual report into deaths, ill health and injuries.

In 2001, Prescott, then the second most powerful man in the country, summoned the industry to a conference centre in the middle of London to sort out its safety record.

The fact he was deputy prime minister gave the safety summit at the QEII venue in February that year real weight. No one of such a rank before or since had personally – and so publicly – intervened on this issue in this way.

As the past few years have shown with the bewildering number of mostly forgettable construction ministers, the industry, despite the numbers of people it employs, the things it builds and the GDP it contributes to UK plc, remains a Cinderella sector in the eyes of successive governments.

People still hark back fondly to Nick Raynsford’s time as construction minister – technically minister for housing and planning. He liked it and seemed to get it. He was in the role between 1999 and 2001 and stepped down as an MP nine years ago.

When Prescott announced his safety summit, 86 people had died on sites in 1999/00 and the number went up the following year to 105. Between April and September 2000, the number of site deaths stood at 62.

For those couple of years, the issue was a real crisis for the industry – the equivalent of Carillion or ISG going down.

A former union official, Prescott decided to act. He called a safety summit and told people to be there. If you weren’t, then you weren’t serious about doing something about it. He told contractors things had to change and put the issue at the top of the construction agenda because he was making it government’s business too.

>> From Building’s archive in 2005: John Prescott’s £60k house challenge

Prescott said he welcomed any measures to improve health and safety but warned that a culture change was necessary.

He said: “Construction is a macho industry, which tends to undermine the essential requirement of a comprehensive safety culture.” He also told designers to put more thought into the safety requirements of constructing, repairing and maintaining buildings.

So, what is its legacy? As someone who went to the summit all those years ago a bit of context is required: Prescott was right, health and safety was too far down firms’ priorities. The industry’s health and safety record was shocking. It was, essentially, killing far too many people with its slapdash approach. Cultural change was required.

Since then, there has been a much greater emphasis on health and safety. The other day, a chief executive told me that he sleeps pretty soundly – usually. But the biggest thing that keeps him awake at night is the thought of someone dying on his jobs. “It would be horrendous,” he said, “because we’d have killed someone.”

Cultural change has happened in health and safety. It is not perfect and the industry’s record needs to improve, still.

Last year, 51 workers died on sites with construction the industry with the biggest number of fatalities more than double the next on the list – the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector. The annual average for the previous five years in construction was 42.

If he were still in post, Prescott would no doubt want to bang heads together again and get the number heading south. The industry should be grateful he, the deputy prime minister, intervened in 2001 and tried to make a difference. Because someone had to.

What else did John Prescott achieve?

The Urban Task Force

The Urban Task Force (UTF), established in 1998 under the Department of Environment, Transport and the Regions, was a key part of John Prescott’s strategy to tackle urban decline, writes Ben Flatman.

Chaired by architect Richard Rogers, it aimed to identify the causes of urban decline and propose a vision for revitalising cities through design excellence, social wellbeing, and environmental responsibility. Members included planner Peter Hall, Lorna Walker of Arup, and Alan Cherry of Countryside Properties, reflecting a multidisciplinary approach.

In its 1999 report, Towards an Urban Renaissance, the UTF made over 100 recommendations, advocating for sustainable, compact, and well-connected urban development. Key proposals included prioritising brownfield development, increasing housing density, reforming planning systems to engage local communities, and investing in public transport and design quality. The task force sought to shift development away from car dependency and suburban sprawl.

The UTF’s work influenced government policy, including the 2000 White Paper Our Towns and Cities – The Future, and shaped planning guidance such as PPG3, which focused on brownfield housing. While debates remain about the long-term success of its vision, many British cities experienced significant regeneration and urban residential growth from the late 1990s until the 2008 financial crash.

£60k house

The £60,000 house initiative, championed by John Prescott, sought to revolutionise affordable housing through modern methods of construction (MMC) and public land use.

The competition, aimed to deliver innovative, low-cost homes. By removing land value from house prices and embracing modular design, the scheme aimed to reduce average construction costs while setting a new standard for sustainable, high-quality housing. However, the programme also raised questions about long-term durability and the financial viability for developers.

Critics claimed that the true cost of the homes was not clear, and issues with quality beset the project once on site. These setbacks cast a shadow over the ambitious initiative, raising doubts about the durability of MMC homes and its ability to deliver on the promises of affordability and sustainability.

Housing Market Renewal Initiative

Prescott’s Housing Market Renewal Initiative (HMRI), launched in 2002, aimed to tackle declining housing markets in nine regions across the North and Midlands of England, including Merseyside, Manchester, and Newcastle.

The programme focused on demolition, refurbishment and new construction to revitalise neighbourhoods affected by the decline of traditional industries. Supporters argued it would reconnect failing housing markets to regional economies, improve communities, and attract residents back to these areas. However, opponents criticised it as destructive, citing the widespread demolition of Victorian terraces, particularly in the North-west, as a loss of heritage and accused it of being a form of “class cleansing.”

The initiative faced growing backlash, including protests from local residents and heritage groups such as Save Britain’s Heritage, which condemned the demolition of historic homes.

Critics highlighted cases like forced evictions under compulsory purchase orders and pointed to concerns that the programme created demolition sites without delivering promised regeneration. By 2011, under the coalition government, funding was withdrawn, leaving some areas unfinished and fuelling criticisms that HMRI’s legacy was more about disruption than renewal.

Despite its controversial reception, the scheme reflected Prescott’s ambition to address urban decline and housing market failures, albeit with deeply divided outcomes.

No comments yet