The UK aviation industry is clamouring for an airport hub but opposition makes any location a potential headache for the government. Ike Ijeh navigates a route through the row

Few infrastructure issues divide opinion as vociferously as that of airport expansion. The Department for Transport forecasts that UK air passenger demand will increase to 465 million passengers by 2030, more than twice current levels. Despite vehement opposition from a vocal environmental lobby, the question facing the government and the country now is not so much whether this capacity should be provided but how. And this is where the trouble begins.

The single issue that crystallises the ferocity of the debate surrounding airport expansion is the proposed third runway at Heathrow. Heathrow remains the world’s busiest airport in terms of international passengers and its total passenger traffic is only exceeded by Atlanta and Beijing. Furthermore, along with London’s four other international airports; Heathrow is the key player in the world’s largest aviation hub which handles 60% of all UK air traffic.

But Heathrow, Britain’s only international hub airport, regularly operates at almost 99% capacity. Furthermore capacity is so restricted at London’s other airports that the region is barely able to meet current demand much less the massive medium to long-term increases forecasted. At a time when emerging global markets are hungrily demanding new aviation routes which we, unlike several of our European rivals, are currently ill equipped to provide, industry commentators have peddled dire warnings about how a failure to urgently address the situation could wield irretrievable damage to the UK’s economy, competitiveness and reputation.

With long-term planning caps in place at Gatwick and City airports, the last Labour government’s solution was to build a third runway and sixth terminal at Heathrow. This option has now been unanimously rejected by all main political parties in a move that provoked rapture among environmentalists and a hail of derision from the business community and aviation industry.

New proposals have since entered into the fray, including regional airport expansion, split-hubs and a new airport on the Thames Estuary. The sceptre of sustainability haunts them all, simply put, how can the government expand air capacity while keeping to its commitments to cut carbon emissions? And, with signs that the coalition (at least the Tory contingent) may be softening its opposition to a third runway and ominous reports from the village of Sipson, (destined to be flattened if the runway is ever built) that BAA is refusing to sell back the properties it acquired, the Heathrow question persists.

The situation has not been helped by the fact that the third runway proposals have now been replaced by the default policy position of all fragile governments: limbo. The coalition’s aviation consultation was initially due to be announced in March. It was then delayed until July and has now been postponed again until later this year. Predictably, the reaction from aviation bosses has been scathing. Tim Clark, president of Emirates Airlines, dryly confessed to being “just a little bit curious” about the UK’s aviation policy and the acerbic British Airways chief Willie Walsh lambasted the government for having “no idea”.

There are of course myriad options from which the government could choose to address the critical problem of aviation capacity in the South-east. Below we examine the three headline proposals and assess the effect they may have on the economy, environment, public transport and passenger experience.

THE HEATHROW OPTION

Proposal: Construction of a third runway and sixth terminal

Estimated cost: £8bn*

Estimated construction schedule: 10-12 years*

(*BAA forecasts)

Economic impact: “Every time someone in the British government says ‘no’ to a third runway, Schiphol [Amsterdam airport] boss Jos Nijhuis thanks me”. BAA chief executive Colin Matthews’ sour anecdote wryly illustrates the damage many are convinced is being wrought on British competitiveness by the government’s (current) refusal to expand Heathrow. While Heathrow pleads for a third runway, both Paris Charles de Gaulle and Frankfurt already have four and Schipol is planning its seventh.

According to leading Tony Travers, leading London School of Economics economist and local government expert, “there are solid economic arguments for Heathrow expansion.” Amid a recession and high unemployment levels, it is estimated the project would create 65,000 jobs and unlock billions of UK inward investment as a result of London’s global hub status being maintained and the new trade opportunities presented by new routes with emerging markets. The third runway is also backed by an unlikely coalition of senior business executives and Britain’s biggest unions and a recent report by management consultants Parsons Brinckerhoff concluded that it was the “best option for hub capacity growth”.

However, Travers counters that Heathrow expansion would be dogged by “extensive opposition” and that development would eventually hit a “planning ceiling”. Simon Rawlinson, head of Strategic Research and Insight at EC Harris, agrees. “At some point Heathrow will just become too difficult to develop, the third runway is only a medium-term solution at best.”

Nonetheless, when it comes to Heathrow’s economic impact, one suspects that many of the west Londoners so opposed to its expansion wish to have their proverbial cake and eat it. The Heathrow “aeropolis” is the UK’s largest employment zone and is directly or indirectly responsible for almost 100,000 jobs. This provides obvious economic benefits for local residents, the majority of whom must have at least been nominally aware of the airport’s existence when they chose to move to the area.

If it was that unpleasant to live near Heathrow then west London house prices wouldn’t be as high in comparison to rest of London as they are

Tony Travers, LSE

As Travers succinctly explains, “fundamentally, if it was that unpleasant to live near Heathrow then west London house prices wouldn’t be as high in comparison to rest of London as they are. Those local residents opposed to Heathrow expansion seriously risk damaging the economic prospects that probably attracted them there in the first place.”

Environmental impact: London mayor Boris Johnson and campaign group Friends of the Earth make unlikely bedfellows when they both insist that a third runway at Heathrow would be an “environmental disaster.” David Nussbaum, chief executive of the World Wildlife Fund, has also claimed that the new runway would be the “single largest source of carbon emissions in the UK”. Rawlinson too concedes that there is “clearly a legitimate noise impact concern on Heathrow’s neighbours.”

But some, including Tim Yeo, chairman of the energy and climate change committee and former Conservative Environment minister, have now reversed their opposition to the third runway and cited new EU carbon caps, charges and trading permits as a means of ensuring that expansion does not unduly accelerate CO2 emissions. And the position taken by many in the aviation industry is that not building a third runway will produce no strategic climate change benefit as the additional capacity will merely be provided by London’s grateful European rivals anyway.

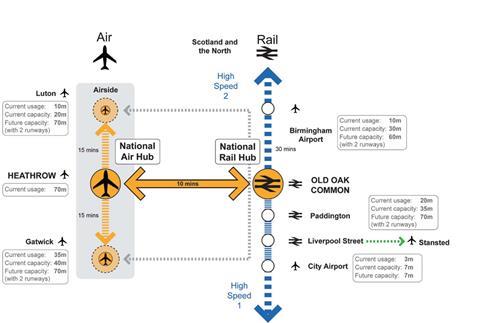

Public transport impact: While Heathrow already offers multiple public transport options, most of them suffer from prodigious journey times to central London and beyond. The exception is the 15 minute Heathrow Express rail link to Paddington, but this is prohibitively expensive to most non-business commuters. A third runway will also benefit from the spur line from Crossrail and might be able to utilise the planned HS2 interchange at nearby Old Oak Common and thereby integrate Heathrow into the national rail network for the first time. But the latter is far from certain as the government has tacitly presented high speed rail as a pseudo-alternative to airport expansion rather than its compliment.

Design and passenger experience potential: As EC Harris’ Rawlinson points out “consumer demand is changing and airlines and airport operators are increasingly prioritising passenger experience. This is one reason for the emphasis on retail at Heathrow Terminal 5.” In design terms, if a sixth terminal is ever built it will hopefully capture some of the exhilarating design quality so painfully absent from most UK airports but frequently evident abroad. It may also provide an opportunity to impose cohesion and legibility on Heathrow’s historically shambolic architectural character, a process already begun by RSHP’s landmark Terminal 5 and Foster + Partners’ current reworking of the Terminal 2.

THE THAMES ESTUARY OPTION

Proposal: Two international hub proposals have been tabled, a Lord Foster scheme comprising a four-runway, 150 million passenger airport on the Isle of Grain and a similar sized floating airport in the same area nicknamed “Boris Island”.

Estimated cost: £20bn*-£70bn

Estimated construction schedule: 6**-14* years (*Foster + Partners forecast; **mayor of London forecast)

Economic impact: If a Thames Estuary airport is ever built it will be the biggest in the world and will have a seismic effect on the South-east’s urban landscape, the UK economy and global aviation structure. But it is a gigantic “if”. “If you believe the single hub model is the most competitive” explains Travers, “then the least problematic option is a new airport on the Thames Estuary. There would be enormous economic gains in terms of regeneration and employment for the local area, most of which is still chronically deprived. Yes, there would be opposition from Kent and Essex but it would be smaller than in west London.”

And what would a new Estuary Airport mean for Heathrow? “Most likely closure” continues Travers, “or it evolves into some kind of smaller cargo port, the whole point of a hub is that you don’t have more than one. This however could have a cataclysmic effect on west London’s economy, similar to the shockwaves experienced in east London when the docks closed. It would radically tilt the economic geography of London.”

Rawlinson shares the belief that the Estuary option is a “viable long-term solution” and would ensure we can compete with “aggressively expansionary Middle Eastern airlines and hubs.” But he is less convinced about the ability of the current Thames Gateway to satisfy the economic growth potential of a vast new hub airport. “Had there been more investment there in the seventies then it might be in a better position now to utilise the full impact of growth. In China they plan cities around airports and not the other way round, 16 businesses a week are said to be opening around Munich Airport.”

An existing hub is a powerful magnet, moving it is a huge operation, everybody would need to be signed up

Simon Rawlinson, EC Harris

London mayor Johnson has claimed that like Chep Lap Kok in Hong Kong, the new airport could be built in as little as six years and be funded entirely by private foreign investment. “Possibly but the timescale’s optimistic,” muses Travers. “Few countries have a planning system as institutionally inclined towards opposition as ours, look how long T5 took. Foreign investors only bought into HS1 after it got going, as yet Crossrail and HS2 haven’t attracted any. The government would have to commit to clearing the considerable planning hurdles ahead to attract funding from abroad.”

Rawlinson shares this scepticism, pointing out that “private investment likes certain rates of return of which privately funded UK transport infrastructure, such as the M6 toll road, does not have an impressive history. The construction risk would also have to be underwritten by the government.” Rawlinson also believes that as BAA has already made clear, the shift from Heathrow to the Estuary would have to be absolute and completed in one go. “An existing hub is a powerful magnet, moving it is a huge operation, everybody would need to be signed up.”

Environmental impact: One of the most vociferous opponents of “Boris Island” has assumed the unusual form of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. RSPB director Chris Corrigan dubbed the plans “utterly absurd” after revealing the estuary is a “major migratory route” and is a natural habitat for an “immense number of birds and wildlife.” The counter argument maintains that the estuary is an isolated location with relatively few residents and thereby represents the lesser of two evils when compared to the noise and environmental disruption endured in congested west London. Moreover, Rawlinson claims that the hub model is actually a “sustainable option that can accommodate bigger, fuller aircraft and achieve greater ground capacity which in turn increases efficiency and minimises impact.”

Public transport impact: The isolated estuary location would enable the new hub to operate 24 hours a day, demanding an extensive public transport network. The ubiquitous Crossrail would probably serve it with yet another spur line. Fast rail connections to London and Europe could also be achieved via a link to the nearby HS1 line and another possible dedicated high-speed rail link that would reach the capital in 20 minutes. A new high-speed catamaran service may also provide a link with central London and further revitalise Thames riverboat services. And the airport’s proximity to the proposed London Gateway deep sea container super-port would also provide obvious benefits with regard to integrated cargo transportation.

Design and passenger experience potential: Plans are at concept stage so no firm details yet. Seamless passenger transfer to London and beyond will be critical. Foster’s involvement will hopefully deliver the visionary airport design that has been his trademark.

THE TWIN HUB REGIONAL EXPANSION OPTION

Proposal: Various split hub proposals have been suggested, including “Heathwick” (Heathrow/Gatwick) and London/Birmingham via HS2.

Estimated cost: Varies

Estimated construction schedule: Varies

Economic/ public transport impact: It seems almost obscene that while South-east air capacity is creaking at the seams, Birmingham airport wails that it is virtually “empty.” According to Neil Bennett, partner at Farrells Architects, this proves that solving London’s capacity crunch requires a national solution. “A third runway won’t solve the long-term capacity problem and an Estuary airport is not only high-risk but would have devastating economic consequences for Heathrow and City airports. Both detract from the bigger issue. By using all your assets and linking them incrementally by high-speed surface transport, capacity can be improved by relatively small measures that respond directly to demand”.

For Bennett, the answer lies with HS2. Farrells’ proposals for a HS2 super-hub transport interchange at Old Oak Common in west London will theoretically place Birmingham within 40 minutes of Heathrow. The two could then operate as a twin hub, which raises the geographically surreal prospect of London Birmingham Airport. “It would require seamless airside links” maintains Bennett, “but the twin-hub, co-sharing format could increasingly reflect emerging airline alliances. To a degree, similar arrangements are already in place at New York, Tokyo and Moscow.”

Bennett also believes that new high-speed links could also create twin hubs between other existing airports. “Heathwick would require Gatwick to improve its transport links but there is also potential for better north-south links between Gatwick and Luton and a Crossrail spur also opens up the possibility of expansion at Stansted. Why do landing spots at Heathrow sell for an average of £25m while those at Stansted are virtually free? Location. Better transport links could help broaden demand.”

Not everyone is convinced. Fears have already been raised that ticket prices on HS2 may be prohibitively expensive. Rawlinson also surmises that joint-ownership consequences would have to considered with regard to split or twin-hubs and that they require a big infrastructure investment. “It somehow feels botched, it would address the capacity issue but is it feasible?” Although he maintains that expansion of regional airports such as the newly christened London Southend may help with regard to short-term capacity distribution, they are not long-term solutions.

Environmental impact: Bennett believes that when it comes to aviation capacity, the nation has to decide what it wants. “Is it more sustainable to build expensive, high-risk new airport infrastructure or spread the load by building around existing settlements with under-capacity and exploiting the opportunities that presents for consolidation and growth?” The twin hub option certainly chimes with environmentalists too who constantly stress that when viewed as a whole, London already has six runways and sufficient capacity which just needs to be managed more efficiently.

Design and passenger experience potential: Although Travers acknowledges that Birmingham Airport has potential, like BAA, he is not convinced the twin hub option offers the same critical “seamless” passenger experience presented by the single hub. Rawlinson flatly asserts that “Birmingham is not a hub location.” The split-hub option does however introduce a new infrastructure typology whose enormous design potential is already reflected in Farrell’s ambitious plans for Old Oak Common, the “super-hub transport interchange”.

HIGH FLYERS IN THE AVIATION ROW

BORIS JOHNSON

London’s Vaudevillian mayor recently instructed the government to stop “pussyfooting around” and invest in big infrastructure projects like his pet ‘Boris Island’ airport. While Boris’ proposals are typically low on detail, his single-handed pursuit of an Estuary hub displays a heroic sense of ambition, determination and vision sorely lacking from the government.

LORD FOSTER

Foster is a virtual deity within architectural circles and his unequivocal support for a new Estuary hub lends it considerable intellectual legitimacy. Foster’s avowed personal interest in aviation adds additional credence to his position, he once claimed that his favourite building was the Boeing 747 and his seminal Stansted Airport remains one of the few masterpieces of UK airport architecture.

JUSTINE GREENING MP

The transport secretary has kept her personal views on aviation expansion to herself pending the delayed consultation, although she is a staunch opponent of a third Heathrow runway. This is in line with the official Conservative policy but critics claim that Greening’s obduracy is motivated more by her Putney constituency being under the Heathrow flight-path rather than by national interest.

WILLIE WALSH

The caustic boss of British Airways is the government’s aviation nemesis. Walsh has poured scorn on the government ever since it cancelled Heathrow expansion and the coalition’s subsequent inertia has his inflamed his ire. His views are shared by BAA chief Colin Matthews but with Walsh one has the impression that he is just one government u-turn away from digging the third runway himself.

Onwards and upwards?

All commentators seem to agree that the only thing that is certain is that demand is growing and that the government will eventually have to respond with a coherent plan for the future. “I would like to see in the government consultation is a clear indication of a forward option,” says the LSE’s Travers, “It must encapsulate a solution. The unequivocal way in which the government has backed HS2 is actually a good precedent. They need to take a risk.”

Is doing nothing an option? “Perhaps but limited capacity will eventually have a social equity consequence, flying would become solely for the rich and the no-frills airline industry would collapse.” Bennett implores the government to look at “all options, from doing nothing to doing everything and to adopt an integrated transport approach.”

Clearly, the environmental issue will have to be factored into any proposals. While the revelation from a 2008 UN report that the global shipping is responsible for twice the carbon emissions of the aviation industry will do little to render celebrity backed campaigns against a Heathrow third runway a less glamorous crusade than picketing cargo ports at Felixstowe, it does illustrate the dogma and distortion that has skewered the climate change debate.

Nonetheless much work will have to be done to ensure that any airport expansion programme does not have a detrimental effect on the environment. Boeing has joined NASA’s Silent Aircraft Initiative which aims to develop new technologies for quieter planes. And the International Air Transport Association (IATA) is committed to ensuring that more efficient aircraft and loading, more sophisticated bio-fuel mixes and more organised air traffic control management reduces the aviation industry’s CO2 emissions by 50% by 2050.

Rawlinson’s claim that the debate “isn’t actually about UK capacity but how you maintain hub status” certainly resonates in a world of rapidly emerging markets, new airline alliances and expanding Asian hubs free from the political and planning constraints exercised in the UK. Whatever strategy we eventually adopt anything has to be better than the political indecision and uncertainty that is currently paralysing the aviation industry. One way or the other the government needs to provide vision, leadership and direction sooner rather than later. The ball is squarely in its court.

No comments yet