Thanks to a streamlined procurement and design process, councils can now choose a school from a brochure and get it delivered in just 13 months. Is this a revolution in the classroom

Never has there been greater pressure to deliver public sector projects more cheaply. The coalition government is slashing council budgets by up to 8.9% this year with more to come, the Building Schools for the Future programme has been comprehensively shredded by education secretary Michael Gove, who is adding insult to injury by demanding 40% savings from already procured schools. Furthermore, the chief construction adviser, Paul Morrell, is fending off government pressure to drive public sector procurement costs down by promising that the industry can deliver savings of 10%-30% by coming up with more efficient ways of working. If the industry is to survive this perfect storm it must come up with a radical response.

But how is it going to deliver? We’ve had the Latham and Egan reports, with their claim that partnering, standardisation and off-site manufacture is the road to the nirvana of reduced costs. Despite all the talk, it turned out to be water off a duck’s back for an industry which likes the old ways far too much. Off-site manufacture and standardisation has never taken off in the way Egan envisaged and at the first sniff of recession the industry lurched away from collaborative forms of procurement back to lump sum tendering.

But amid this devastation comes salvation in the form of a glossy catalogue from a company called Sunesis.

The name Sunesis conjours up the same promise as a holiday brochure in the middle of a sub-zero winter. However, instead of sun-drenched beaches it offers school buildings. In fact, it is closer to a car brochure than a travel ad. You see a model you like and hey presto, you can order it.

I am hoping that once we get going, the supply chain will innovate to save costs, as the process is standardised and they will have continuity of work

Steve Elkin, Sunesis

With Sunesis you get a choice of three models: the Paxton, the Keynes or the Newton. There are attractive pictures in the catalogue, complete with labels pointing out the key features. Like a car pamphlet, the back is dedicated to features and specification, detailing how many rooms you get for your money and how big they are. It tells you how much energy the school uses and, if you have more money to spend, there are souped up versions with better energy performance. The best bit is you can have a shiny new school for a fixed price with a guaranteed delivery time of just 13 months.

Welcome to a timely answer to the current crisis. Sunesis is an off-the-shelf, standardised set of designs that are claimed to save 20% over the cost of an equivalent bespoke school.

The bulk of these savings comes from a streamlined procurement and design process. For a start, design costs are minimal which might be bad news for architects, but is great for buyers. Wave goodbye to the time-consuming, expensive consultation culture - there is no need for local authorities, head teachers, designers and contractors to spend hours in meetings debating where the toilets should go. All those feasibility studies, consultations, design reviews and legal paperwork can take up to 18 months for a standard school. Sunesis claims it can get a school on site 16 weeks from the date of the order. Built in is an assumption that 12 of those weeks will be taken up by getting it though planning.

Given time and a ready market, costs could drop even further. Only a third of the 20% saving is down to the standardised build process, which could be made tighter. “The savings could eventually be as much as 30%,” says Steve Elkin, who heads the contracting arm of Sunesis. “I am hoping that once we get going, the supply chain will innovate to save costs, as the process is standardised and they will have continuity of work.”

The big idea

Sunesis was born out of the relationship between contractor Wilmott Dixon and Scape, the one-stop building procurement shop run by councils for councils. Scape sets up framework deals with contractors for a fixed value of work and gets it through the time-consuming OJEU tender process. If a local authority wants a school, it can go to an organisation experienced in delivering these types of projects and as the project value is pre-tendered they don’t have to wait nine months to go through OJEU.

Willmott Dixon enjoys a £350m single supplier framework with Scape, an arrangement both parties say promotes collaboration and innovation. “You can really get into bed with your supplier and innovate,” says Mark Robinson, the chief executive of Scape, a sentiment echoed by Willmott Dixon’s Elkin. But doesn’t the single supplier relationship work against efficiency by reducing competitive tension? Not according to Elkin. “We tendered for this incredibly hard as we knew the exclusivity was valuable. There are lots of key performance indicators to meet and if you don’t do that you get kicked off. The stick is always in the background.” Robinson says a single supplier framework also eliminates bidding costs, which keeps total costs down. “That expenditure comes back to the client,” he says.

Robinson says the idea for Sunesis came out of conversations with council leaders. “I deal a lot with local authorities,” he explains. “I have had years of them saying: ’This school is going to cost £5m, but I don’t know what I’m getting for my money’. With the catalogue they know exactly what they’re getting.”

Elkin adds that headteachers and local authorities aren’t interested in the long, drawn out consultation and procurement process: all they want is a school that works. “It’s how you buy everything else,” he says.

With over £300m worth of projects already under their belt, Scape and Willmott Dixon reckon they have a very good idea of what a council wants from a primary school. They have based the Sunesis designs (see box) on the best Scape projects. For example, the Paxton (see box on page 48) started off as a Scape design at Kingsmead school in Cheshire, then was procured by Monmouthshire first for a school in Wyesham and then Llanfoist, which has now been packaged up as a Sunesis school. Councils get a choice of colours and finishes and can customise some elements within the basic envelope of the building. Like a car, the design is progressively refined, with feedback incorporated into the next iteration.

According to Sunesis, reaction to the concept has been positive and a dozen councils are “champing at the bit” to sign up - it will be available from the end of this month. Sunesis want to extend the concept to other building types including leisure, healthcare and, crucially, secondary schools. “We are pretty close to coming up with a fixed external design but you can configure the internal space,” says Robinson. “A lot of our clients have already expressed interest in a Sunesis secondary and we have been to see the education department, who are keen on this.”

Given the tough new world of public sector procurement, Sunesis could just be the tonic the industry needs.

What do you get for your money?

Sunesis plans to launch its service with three different primary school designs. These vary according to site constraints and the budget of the client. The price of all the schools includes car parking, a hard court games area, markings for a running track and security fencing for the site.

The Keynes sits firmly at the no frills end of the range with a price of £2.3m and delivery time of nine months. This buys you an Atkins-designed single form entry primary school with 1,277m2 of space including a school hall. The building is a simple rectangular box with a central corridor and has an EPC rating of B and a BREEAM rating of “very good”. It is built from laminated timber panels that are left exposed on the interior. Cladding choices have yet to be finished, but may include brick and render or metal and timber clad.

An extra £200k buys a steel-framed version which has the advantage that it spans the width of the school. This means the interior can be reconfigured easily, unlike the cheaper version. It also comes with more traditional brick and render cladding and is available in bigger versions, with or without nursery.

If you want to go upmarket, the Paxton could be the answer. This White Design-penned school costs significantly more than the Keynes at £3.8m but this buys 1,583m2 of space - it has more teaching and support rooms and a bigger main hall than the Keynes. It is also curved in plan which makes it visually more interesting and it features a glulam frame plus rainwater harvesting and underfloor heating as standard.

It has the same EPC and BREEAM rating as the Keynes, but spend another £300k for a super-insulated version complete with triple glazing and the performance jumps to an EPC A rating and BREEAM “excellent”. Delivery is longer than the Keynes at 13 months.

Finally there’s the Newton, which has been designed by Scape and is intended for sites next to busy roads. This guitar plectrum-shaped, £3m school features a courtyard at its centre with the teaching and other rooms arranged around it. The idea is that the courtyard will provide a safe haven for play. The design is also suitable for schools who have pupils with behavioural difficulties as they can be easily supervised.

The Newton features a lightweight steel frame and a metal cladding system. It has the same energy performance and BREEAM rating as the other two schools and like the Paxton an extra £0.5m buys an EPC of A and a BREEAM “excellent”. Delivery is 12 months.

Sunesis is also considering whether to launch the Dewey, a two- to three-story school designed for tight sites.

What is a Sunesis school like?

To many people the mere mention of price-driven, standardised designs will conjure up visions of uninspiring boxes that look even worse as these age. And Sunesis is the first to admit its designs aren’t poised on the cutting edge of modern architecture. So what are Sunesis schools like? The Paxton has been built in several locations around the UK with the latest incarnation being Llanfoist Fawr primary school in Abergavenny, south Wales - so Building went to have a look.

The school is certainly no worse than many built in the last few years. Instead of a simple rectilinear design, it has a gentle curve. This adds visual interest and means the central corridor inside the building is less intimidating to primary school children than a long, straight one. This school cost £4.5m but as a standardised design it will come in at just £3.8m.

The building was designed by eco-architect White Design and features a glulam frame. This protrudes beyond the building envelope and features external timber columns. The frame is also expressed inside the building, which again creates a visually stimulating interior, with the timber adding a warm feel.

Internally the layout is simple and logical. The entrance is located in the middle of the curve and the corridor runs down the middle of the building. The classrooms are all on the side of the corridor away from the entrance; each room has access to the play area at the rear through a small room that can also be used for one-to-one tuition. The staff room and offices are to the left of the main entrance and a generous school hall to the right acts as a feature breaking up the exterior facade, as it steps out from the rest of the building envelope. The hall doubles up as a dining room.

Sunesis has concentrated on keeping construction costs down and making the building simple to maintain. The attractive glulam beams are a standardised product used to build barns for storing road salt. Timber frame is used for the walls and infilled with insulation, then overclad with white render, with brickwork at the base.

The original school in Cheshire on which Llanfoist is based featured timber cladding and natural finish aluminium windows which looks better than the cladding and blue-finished windows specified here. Many local authority clients see timber cladding as risky. “Clients often prefer something traditional rather than a fancy cladding system that goes out of fashion,” explains Robinson. The school colour is blue which explains its use on the windows which are a Velfac product.

Headteacher Mary Larner is delighted with her new school. Before it arrived, the school was housed in a hotch potch of Victorian buildings with outside toilets, combined with temporary accommodation. She describes procuring the school as a “lovely experience”. “The design was handed to us but we had the chance to change it,” she says. “We are not architects so it’s quite nice to be given a design and have the chance to modify it. We were very keen to make this feel cosy and feel like home.”

She adds that knowing the school design had been built elsewhere was reassuring and, for her, the curved design is a successful feature. “I could see the idea behind the curved corridor, its cosy inside which helps make the children feel secure,” she says. “I’ve seen schools with long corridors that look like hospitals.”

Any gripes? Larner says the playground could do with more “nooks and crannies” for the children to play in. The school also features a bike shed that is inside the school envelope, which seems an extravagant use of space but it turns out this is a Monmouthshire council requirement. Sunesis says this could easily be converted to a classroom and that if they get regular feedback about features that don’t work for users, they will change it for future versions.

The clients

Julian Humphreys, design and construction group manager, Warwickshire council

Doing nothing in relation to schools is not an option. So I applaud Scape and their partners for coming up with this concept. I’m not yet convinced the idea as it stands is robust enough - there is work to do, but we’d look forward to working collaboratively to work up a product that meets our needs.

I don’t really like the motor industry analogy, but to borrow it: I can see the sense in it, and think we ought to embrace what’s good about a systemised approach - but we still need to create an environment that inspires and performs. I’m not convinced the Ford Focus does. I think it’s entirely doable to create an inspiring space for the money available. We don’t need to blot the landscape.

We know that as an industry we need to be targeting savings of about 30%. I think that that can be achieved, but we need to be clear about what’s cost and what’s price, and make sure that it’s the cost that’s being driven down.

Barbara Morgan, head of facilities management, Nottingham council

My view is that this is exciting for local authorities as a potential school procurement solution.

The schools offer a good quality learning environment, which is the key issue for our children, but they also offer this at a sensible price. We don’t have the capital resources for large, bespoke schemes any more - those days have gone. From the educational perspective they offer flexible space which is very important if educational needs change or if the building has to be used for another purpose. This flexibility means they can be also used for community use, joint service centres and libraries.

I don’t think the fact the buildings are standardised is a problem. The quality of the learning environment is what’s important. If it serves the purpose it doesn’t matter if it looks like one 20 miles down the road; the parents won’t mind - it’s what goes on inside that counts.

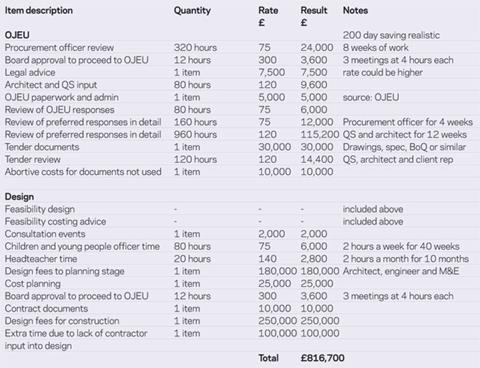

How the savings stack up

Sunesis employed cost consultant Faithful & Gould to work out how much money could be saved on design and procurement using a standardised approach. If the Keynes was procured traditionally it would cost £3.25m. The figures below break down how Sunesis can comfortably deliver a standardised solution for £2.5m.

1 Readers' comment