The fairy-tale castle that is the Midland Grand hotel has been asleep for a very long time. Now the arrival of the Eurostar has roused it, and it is once again to become the most stylish address in London

There can’t be many Londoners who are unfamiliar with the splendour that is St Pancras Chambers. Somewhere between a northern French cathedral and one of Mad King Ludwig’s fairy-tale castles, its curved, red-brick facade is defended with towers and spires and wrapped in bands of sharply arched windows. This is a contender, along with the Houses of Parliament and the Royal Courts of Justice, for the title of Britain’s finest gothic revival building.

Its first incarnation, as the Midland Grand hotel, ended in 1935 when it became too expensive to maintain. Now, after 74 years in suspended animation, a £100m restoration is reviving the grade I-listed chambers as luxury apartments – with the first residents about to move in – and a new hotel on the lower floors.

The restoration is part of a wider regeneration of the area, which began with the transformation of neighbouring St Pancras station into Britain’s Eurostar terminal. The two buildings are not much alike, though – whereas William Barlow’s train shed epitomises brilliant, functional Victorian engineering, George Gilbert Scott’s hotel is all about romance, grandeur and style. It opened in 1876, but was forced to shut 59 years later, mainly because it had only eight bathrooms for 300 rooms. “The toilet was invented six years after it was finished, so this place was redundant almost overnight,” says Geoff Mann, principal director of RHWL, the project architect.

Since its closure, the building has been threatened with demolition twice, turned into drab offices, then closed down and left to rot in the late eighties after the owner, British Rail, could not renew its fire certificate.

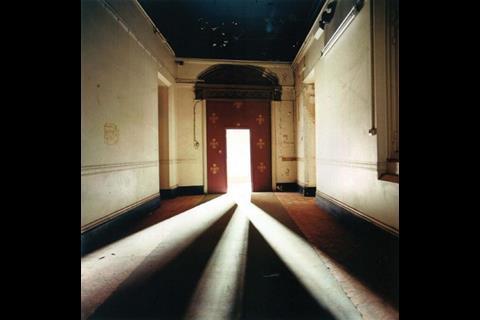

Apart from these crude interventions, the building is exactly as it was when the last guest departed. To walk up its grand central staircase is to step back in time to an age of gas lights and coal fires.

Here, Building exclusively reveals the first images of the completed apartments, and the story of how this London landmark has been revived.

A slow start

“The building had been empty for God knows how long and British Rail had sacrilegiously beaten up the details,” says Mann. “For example, it had bashed holes in the fibrous plaster ceilings to put in hangers for suspended ceilings. All this made it quite difficult to ascertain what was behind the changes, which made it difficult to design.”

On top of this, of course, was the building’s major shortcoming: the lack of toilets. “We had to put them in,” says Mann, “and the plumbing and ventilation, but where in hell do you put all that stuff? The obvious answer was in the chimneys but every single one was full of bricks and dead pigeons.”

So who was brave enough to take on these challenges? The Manhattan Loft Corporation (MLC) stepped up, unable to resist the chance of turning those gloriously gothic, steep roof spaces into modern flats. “We introduced the concept of loft living to the UK, and there’s probably no better attic in the UK,” says Harry Handelsman, the firm’s founder. “I saw it as a chance to create a distinctive identity for a building everyone was in awe of.”

The firm wanted to develop the building jointly with Whitbread, which held the UK franchise for Marriott hotels, but after Whitbread sold its franchise, MLC decided to develop the hotel and apartments alone, then lease the hotel to Marriott. Once in control of the whole building, MLC raised the number of apartments to 67 and extended them to the second floor. “We preferred to have more apartments, as the hotel was more risky,” says Handelsman, “but the way the area has developed, the hotel will probably be the more lucrative element.”

Once it had decided on what it wanted to build, MLC chose Laing O’Rourke in February 2006 to do the enabling works. The initial phases of the job included stripping out rubbish and sweeping away the changes British Rail had made, as well as doing early phases of the services, which had to dovetail with work being done on the train terminal. Inspired by the station, Handelsman decided to upgrade the hotel by adding a presidential suite, club lounges and a better spa. Unfortunately, Laing O’Rourke and MLC couldn’t agree on terms for the main contract, so they parted ways in September 2007.

Handelsman had to finish the critical services that interfaced with the station before it opened in November. He also wanted to avoid delaying the chambers. This is when Galliford Try entered the picture. “We were recommended to Harry, so he engaged us on a short-term basis to do the works needed for the station,” says James Armitage, managing director of Galliford Try Construction’s southern division. “Then our role gradually expanded.”

Armitage says the team liked Galliford Try’s approach, so it was asked to build up a price to complete the restoration. It agreed to a fixed-price deal of £103m, which Armitage concedes was risky, given the unpredictable nature of refurbishing such a heavily protected building. “It was scary to start with, but we were given a lot of time to work up a price with Gleeds and RHWL.” Reece Costain, project director for Gleeds, says: “It went through a really severe review of several months to see if we could deliver on the price, the programme and the quality.”

We had to put lavatories in, and the plumbing and ventilation, but where in hell do you put all that stuff?

Geoff Mann, Project Architect, RHWL

Luckily, MLC felt it could depend on Galliford Try – so much so that the contract was signed only recently, despite the firm having been on the job for 18 months.

With the review done, a major change was made to the phasing of the programme to enable the apartments to be handed over a year earlier than planned. Laing O’Rourke was going to refurbish the building floor by floor, then hand over the whole building. The new strategy was to refurbish in vertical sections working from east to west. This meant staircases and lifts would be completed, allowing residents access to the apartments on the upper floors. The fire escape strategy needed modifying so two staircases would be available when the first phase was handed over.

The new plan also meant the design team had to design the lower parts of the building much earlier than planned.

Signal failures

Unblocking some 300 flues terminating in more than 40 chimney stacks was one of the most challenging parts of the job, says Simon Frawley, Galliford Try’s project director.

“There was a little iron plate fixed onto each chimney stack with the related room number on it so the chimney sweep lads knew which flue to drop their brushes down,” he says. “This meant you knew where the top and bottom of the flue was but not where it was blocked en route. We had to trace the route of each flue and find the blockages using a range of techniques from ground radar to tapping the walls. We then cleared them and installed flue liners. This process took almost a year, but gave us a very good understanding of how the building was put together.”

Another problem was the need to constantly modify the design as obstacles were revealed. A particular problem was the small gap under the floor for the services. In places, obstructions meant the services had to be re-routed (see below). “Luckily the design team are here on site all the time,” says Frawley. “This has made a real difference, as the whole team is on hand to deal with problems immediately. Without that, the job would have been much slower.”

As an added complication, all interventions had to be agreed with English Heritage and method statements drawn up. This process was made easier by carefully documenting the whole building before planning permission was granted. RHWL surveyed every room and included plans and elevations showing where everything was going to go, right down to the electrical sockets. Even the paint on the walls was surveyed and a decision made on which historical layer to replicate. “It was a hell of a lot of work,” says Mann, “but if we hadn’t done it, there would have been constant fights with English Heritage, and we might as well have packed up and gone home.”

The rooms were divided into three groups, according to their historical significance. Seven were classified as “very important”, which means they have to be restored to their original condition. Most of the “not very important” rooms are in the roof, and RHWL has been allowed free rein on them (see below). Elsewhere, English Heritage has allowed fireplaces to be moved slightly and doors to be switched around.

Back on track

Rubbish is the only thing that has left the building; everything else is being repaired or reused. For instance, all the floorboards were taken up and planed down to a uniform size before being reused. Doors have been lightly rubbed down and repainted and windows have been repaired. The big saloon that will become the hotel’s presidential suite is being used as a workshop for this purpose.

The roof and brickwork had been restored in the nineties, so needed very little attention. Still, the plaster had to be repaired using traditional techniques, such as installing new chestnut lathes and lime plaster; cornices had to be run in situ by hand.

Also, new cast-iron details were made for the balustrades and windows, coloured glass was installed in the fanlights over the doors where they were broken. Stonework was repaired or replaced and new lifts were inserted for both apartments and hotels. All the lift shafts are now in place. “Our approach has been to try and get all the heavy work done so when we start on the hotel properly, it’s more of a fit-out job,” says Frawley. At the moment, the windows are being repaired in the hotel areas. This requires internal scaffolding, which needs to be out of the way before the rest of the work starts in this area.

By then the apartments will all be in use. The first owners are now moving in to their flats, and the rest will all be completed by November this year. Work will then focus on the hotel, which Galliford Try will finish at the end of October 2010 and hand over to Marriott for fitting out. The team hopes that by spring 2011 the world will once again be able to enjoy St Pancras Chambers the way George Gilbert Scott intended.

Downloads

Section

Other, Size 0 kb

Postscript

Watch Thomas Lane’s interview with MLC’s Harry Handelsman and RWHL’s Geoff Mann on www.building.co.uk/buildingtv.

Original print headline: 'Sleeping beauty is waking up'.

5 Readers' comments