With the upturn in work has come predictions of a skills shortage. But the CIC’s Jack Pringle thinks the need for architects, QSs and engineers is already so critical that we should be sourcing them from outside the UK and Europe

Eyebrows were raised in some quarters last week at comments made by Construction Industry Council chairman Jack Pringle, who revealed he has been lobbying ministers to lift visa restrictions on architects and other white collar professionals because of a looming skills shortage in the sector.

His revelation was a surprise to many, including the current RIBA president - even though the CIC represents a host of leading professional bodies, including the RIBA, the CIOB, CIBSE, and RICS.

But Pringle, an architect and himself a former RIBA president, is known for speaking his mind and once likened himself to a “streetfighter” when campaigning for the RIBA’s top job. His reasoning was that employers will shortly need to look beyond the workforce of the UK and the EU because construction is poised to move “from famine to feast very quickly”.

Calling the skills shortage a “critical issue”, Pringle said that the government should make it easier for employers to hire architects, quantity surveyors and engineers from other parts of the world by including them on the government’s Shortage Occupation List, a list of occupations in which the UK does not have enough domestic or European workers to meet demand.

So why exactly is he advocating the approach and what does it involve? And could it undermine domestic initiatives to meet the industry’s skills needs or even the job prospects of unemployed or underemployed professionals in the UK?

On the list

The Shortage Occupation List is compiled by the Migration Advisory Committee, an independent body that advises the Home Office. The current list includes jobs from aircraft maintenance workers to chefs to certain types of engineer, including civil engineers specialising in tunnelling.

Those recruiting for jobs on the list - which was last published in January 2013 with a new version expected early next year - are not required to advertise the role in the UK and the EU first. Those in the listed occupations are also given priority in terms of visas.

Pringle’s day job is a principal of Pringle Brandon Perkins & Will, an international architect specialising in commercial work and office fit-outs.

“There’s been a sharp uptick in work over the past four months,” he says. “In the commercial sector, it’s not just my office but everyone I speak to. After a gruelling recession, people shed from offices don’t do nothing. They go into other areas of business or go abroad and they don’t come back. There’s a fairly fixed labour pool.

“We need a flexible labour force to match demand. The last thing we want is a surprisingly brisk recovery stalled by a lack of skills.”

Room for more?

Construction is a notoriously boom and bust industry and statistics do support the premise of Pringle’s argument - that a serious skills shortage among professionals will soon be upon us.

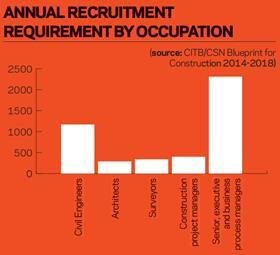

According to Blueprint for Construction 2014-2018, a report released by the CITB’s Construction Skills Network last month, there is an “annual recruitment requirement” in all the professions Pringle highlights over this period (see box below).

The annual recruitment requirement examines anticipated workloads alongside supply-side “churn” in the industry - the numbers of people moving in and out of the sector - but does not include flows in from training.

The report found an overall industry annual recruitment requirement of 36,400 during the period, including 290 architects, 340 surveyors and a whopping 1,170 civil engineers.

Furthermore, according to the latest RICS construction market survey, the proportion of UK QSs pointing to skills shortages leapt from 10% in the final quarter of 2012 to 33% in the final quarter of 2013. The proportion of “other professionals” reporting skills shortages rose even more sharply over this period, from 7% to 34%.

Ann Bentley, chairman at consultant Rider Levett Bucknall, welcomes Pringle’s initiative, saying that the need for worldwide industry recruitment is “clear for all to see”.

“Throughout the recession we lost qualified people when the work slowed down, some of whom left the industry for good,” she says. “But more worryingly, we also have supply constraints at both ends of the age scale with universities reporting fewer UK students applying for QS degree courses and an increase in the average age of the workforce, with many retiring over the next few years.

“In the past, when quantity surveying was on the Shortage Occupation List, we recruited many high-calibre staff from overseas - particularly from Australia, New Zealand and South Africa.

“The market dynamic has now changed, and not only do we have a need for quantity surveying expertise, but also for staff who can converse with foreign investors in their own language - particularly Russian and Mandarin. As a global organisation we employ these staff but the visa requirements make it difficult.”

It is not difficult to find top figures in architecture and engineering who agree. Simon Allford, founding director of AHMM - the rapidly-growing architect working on a new London headquarters for Google and on projects in Holland, the US and Africa - believes the capital in particular would benefit from fewer barriers to international working.

He says: “London needs global reach and talent. If you have a global team of architects, then you have ambassadors who can help you win work all over the world.”

Similarly, chief executive of the Institution of Structural Engineers, Martin Powell, endorses the idea of professionals “moving freely both into and out of the UK” although he cautions that maintaining high levels of competence and professional standards is vital for public safety.

However, despite this positive reception, there are fears that the Pringle plan might harm home-grown professionals still struggling after a brutal recession.

Home-grown talent

The RIBA’s current president Stephen Hodder is one sceptic - pointing to the institute’s Future Trends Survey in December, which found

that almost a fifth of respondents had been under-employed in the past month.

“There may be a skills shortage in the industry but I’m not convinced that’s the case in the architecture profession,” Hodder says. “The statistics demonstrate there is still available resource within the profession, both within existing practices and with people who are unemployed.”

Others caution that fixing a short-term problem might store up problems for the long term in regard to the UK’s ambition to develop a sustainable pipeline of talent to match its pipeline of construction and infrastructure work.

John Perkins’ review of engineering skills, commissioned by the government and published last November, acknowledged the need for engineers to be on the Shortage Occupation List but added that “this should not be our long-term solution”.

Perkins wrote: “We should support the UK’s young people by preparing them to compete for highly-paid skilled engineering jobs, improving theircareer prospects and reducing the need to import engineering skills.”

Even RLB’s Ann Bentley has some qualms, saying: “It is essential that we maintain and build expertise within the UK as well and ensure that we don’t end up with a quick fix that solves the problem today, but leaves us in difficulty further down the line.”

Pringle himself believes his plan would not be at the expense of British talent, predicting that unemployment and underemployment in these professions in the UK will fall sharply in any case in the coming months.

But he acknowledges that he faces an uphill battle convincing ministers to back his approach, calling visas “quite a political issue”. If Pringle is right and famine turns quickly to feast, there may be seats left empty at the banquet.

The UK chief construction adviser’s view

Peter Hansford has welcomed Jack Pringle’s reports of rapid recovery and says if the evidence is there, then occupations like architect and QS can be added to the Shortage Occupation List. But he says he and the Construction Leadership Council are more focused on creating a sustainable pipeline of skills to meet the industry’s long-term needs.

He says: “It is not sustainable to rely on bringing in workers of any occupation from elsewhere. That is why we have a long-term commitment to encourage more people to come into the industry. That is a long-term gain which involves working with school children, higher education and further education to produce built environment professionals.

“What the leadership council is looking at is overall skills requirements for the industry. At the moment, we have a pipeline of work which is imperfect. I’m very keen that the pipeline gets expanded to include local authorities, private sector clients, retail and commercial developers. Once we can get a good handle on the workload ahead, we can understand the skills requirement.”

3 Readers' comments