Technology giant Siemens developed one LEED Platinum-rated office in London, and is now trying to replicate this success - in the Abu Dhabi desert

Hard on the heels of newly opened sustainability showcase the Crystal comes a second major project developed by engineering and technology giant Siemens.

The Crystal boasts a LEED Platinum rating, the highest possible under the US environmental assessment system. Siemens wanted its latest building to be as sustainable as possible, so it will achieve LEED Platinum, too. But this is where the two buildings diverge - the Crystal is located in temperate London, but the new building is being constructed in Abu Dhabi, where summer temperatures of almost 50 degrees are made more unbearable by the relative humidity, which nears 90% at times. When completed, this regional headquarters for Siemens will be the first building in the region with a LEED Platinum rating.

The reason no buildings in the Middle East have achieved this to date is because it is extremely challenging. The target is even tougher because LEED assesses the building post completion, so the Siemens building’s architect Sheppard Robson came up with a design that performed 10% better than required to compensate for potentially poor quality construction. This meant coming up with as many design options as possible and intensively analysing them to find the best solution - a process aided by parametric computer analysis and engineer Aecom.

David Ardill, the Sheppard Robson partner running job, says the cladding design was critical to the building’s energy performance. Deep-plan buildings have less facade relative to floor area compared with shallow plan ones.

“We made a strategic decision at the start to limit the envelope area,” he says. “The floor plan is linked to the facade, which is linked to the energy performance.” This strategy resulted in a building with a floorplate of 81m x 81m. Light is introduced into the centre of the building via nine atriums. The floor slab is post-tensioned concrete, which helped reduce the height of the building.

Ardill says the facade solution had to be as simple as possible to maintain build quality. “We made it as simple and robust as possible to ensure it was airtight, which was critical from the energy point of view,” he says.

The building has to be attractive for people to go to as Masdar is a building site in the middle of the desert

David Ardill, Sheppard Robson

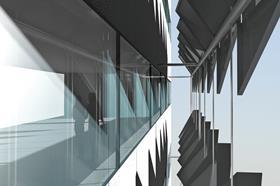

The cladding is a simple, well insulated and airtight planar box protected by a lightweight solar shading system. The box is 65% solid material and 35% glass. The positioning of the glazing was intensively analysed to get the best combination of energy efficiency and natural light. Variations included alternating vertical strips of glazing with solid areas and horizontal strips of glazing at the top and bottom of each floor separated by a solid area. The most energy-efficient solution proved to be a simple strip of glazing 1.5m high starting 900mm from the slab.

The solid areas of facade have been created by the simple expedient of a 900mm-high concrete upstand and 1m-deep downstand extending from the slab. The glazing is sandwiched in the middle. Ardill explains the traditional way of creating a solid area of facade in the Middle East is by using aerated concrete blocks, but this was ruled out.”We found the airtightness would be compromised using aerated concrete blocks due to the poor quality workmanship out there,” he explains.

The solar shading system has been designed to protect the glazed areas almost 100% of the time. It also had to be kept clear of the building to prevent heat being radiated into the building. The solar shading is conceived as a 3D solution and was parametrically modelled. Solar shading elements were rotated, twisted and varied in size and shape to identify the ideal configuration. Then this had to be turned into a buildable solution.

The solar shading elements are made from lightweight aluminium sheet modules braced at the rear for stiffness. These are 1.5m wide. The shape of these elements vary depending on the orientation, so the south side features simple angled fins above the windows as the sun is always high in the sky when facing the building. The north-west side was the most challenging as this has to cope with the setting sun, plus it faces a public square with no opportunity of shading by adjacent buildings. The solar shading elements are much larger and feature two elements - one twisted horizontally and the other vertically to shade the building as the sun moves across and down this elevation. Ardill says the sun will shine directly through the glass for an hour at the end of the day as it is so low - the alternative was an almost solid facade. “We decided this was acceptable as there was less energy in the sun at this time of day and the cooling system could cope with it,” he says. “The building has to be attractive for people to go to as Masdar is a building site in the middle of the desert.”

The shading elements are supported from the top of the building by a series of tension wires anchored near ground level. Metal tubes hold the wires 1.5m from the inner facade to prevent heat being radiated through the glass. The aluminium shades are simply fixed to the wires. The aluminium is painted with a heat reflective paint supplied by Jotun. It is a light grey colour that won’t show the dirt created by sandstorms. The building is under construction and when complete will be a worthy complement to its distant cousin in rainy London.

No comments yet