It’s finally here, and it’s quite unlike any other airport experience in the world. Over the next five pages, Martin Spring imagines what passengers will make of Richard Rogers’ monumental Heathrow Terminal 5. Then, on page 50, we ask whether this groundbreaking project really has changed the construction industry for the better.

Heathrow. The very word is enough to send even the most intrepid of travellers packing for a quiet fortnight in Eastbourne. The world’s busiest airport has, fairly or otherwise, become synonymous with delays, check-in queues of labyrinthine complexity and summer nights spent on the floor sharing a makeshift pillow with an Australian backpacker. In other words, it wasn’t much of a shock to anyone when a poll conducted last September by travel organisation TripAdvisor voted it the worst airport in the world. The only surprise was that it had to share the wooden spoon with Chicago O’Hare International.

When it opens next month, Terminal 5 will be BAA’s chance to change all that. The epic construction project, which took more than 18 years and £4.3bn to come to fruition, has already been lauded for its architecture and groundbreaking construction programme (see pages 50-53). But will its unusual multistorey layout pass muster with the battle-scarred travellers of the world, or just create yet more chaos? Building packed its Hawaiian shirt and Panama hat and went along to find out.

Checking in

As you enter the departures hall, you find the entire top floor of the building spread out in front of you. Looking straight ahead, past the throng of fellow passengers, you can see through the departures gate to the glass external wall on the other side – a distance about one-and-a-half times the length of the pitch at Wembley. To either side, you can see from one end of the building to the other – that’s about a quarter of a mile. It comes as no surprise that Mike Davies, Lord Rogers’ partner who has championed the building throughout the 19 years of development, says it can accommodate three Empire State Buildings lying side by side.

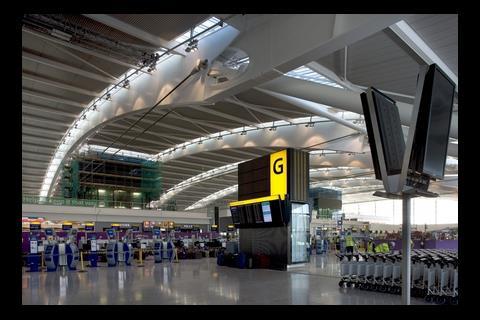

Of course, there is a practical purpose behind these dazzling statistics. From the passenger’s point of view, it makes a refreshing change to be able to see where you are meant to be going, and here the whole check-in procedure has been placed right in front of you. Just ahead of you stands a line of departure boards on upright boxes known as “beacons”, a few steps further on and you’re at the check-in desks – a full 140 of them, arranged in three parallel rows across the open floor. One of the three rows is entirely dedicated to self-service kiosks for passengers who have checked in online, but after that there’s no avoiding the slog through passport control and security.

Break on through

The first thing that hits you as put your shoes back on, and check that you’ve picked up all your loose change, is the view. The window wall ahead of you reveals a panorama of low hills stretching off into the distance. In the foreground, planes land and take off from the two runways that sandwich the terminal.

This is a reminder of the limited space that Davies had to work with when designing T5 – a restriction that led to the unusual solution of stacking the building up to four storeys high. For a 300,000m2 building, such compaction would normally have resulted in a disorientating, artificially lit labyrinth. Not so up here on the fourth floor of T5: there’s a liberating sense of space and airiness, and the view even stretches to the sloping arch of Wembley stadium.

But it’s time to refocus on the airport itself, for this is where BAA’s real moneyspinners – the 112 shops, restaurants, cafes and currency exchanges – crowd in like hustlers in an Arabian souk. Even if you manage to resist the high-street peddlers such as WH Smith and Krispy Kreme Doughnuts, higher class merchants such as Harrods and Paul Smith are waiting to fleece you of your travel expenses.

Here we’ve reverted to standard-issue airport terminal surroundings. But if you don’t want to be inveigled into a shop or coffee bar, and just want to sit down and wait for your flight departure to be called, there are no seats to be found. This being a multistorey terminal you have to find an escalator downwards. Fortunately there are 131 of them in the building.

On the floor below – once you have picked your way beyond yet more shops – you finally arrive at a double-height hall with comfortable slimline seats (designed, incidentally, by Foster + Partners).

This isn’t a bad moment to sit back and marvel at the greatest construction feat of terminal: the powerful, sweeping roof. This vast expanse, which does not have a single intervening column, comes across as a magnificent engineering structure in the tradition of the great 19th-century railway stations – down to the plain white finish and exposed bolt heads (see box, opposite). There’s none of the fruity colouring or touchy-feely bamboo linings that helped win the 2006 Stirling prize for Rogers’ other terminal at Barrajas airport in Madrid. Nor are there any ducts or cables snaking overhead. And it is not as if the building is naturally ventilated – for a terminal in the heart of Europe’s busiest airport, that would be asking a bit much. But the conditioned air is craftily supplied through the flight information “beacons”. It is then extracted through five bulky towers that rise up between the check-in desks and duty-free shops, nearly to roof level.

To the gate

Now your flight is being called, and you make your way to the departures gate. And here’s another novel twist to the standard passenger traffic system. Even though you’re still on the third floor, you don’t have to go down to get there. Instead you walk along the same upper floor to another spacious seating area. It is only after the boarding gate is opened by airline staff that you descend into the building’s perimeter void. From here, you either pass through a pair of doors onto the clear-glazed link bridge to your plane or take another escalator down to the basement and hop on an underground shuttle train to one of T5’s two long, low satellite buildings.

It is one of the few stages of your journey where you are cut off from views, but at least the shuttle is fast: the journey takes only 45 seconds.

Take-off

And so you take your seat on the plane. Now, was getting here a fraught assault course or a pleasurable experience? If your flight departure was on time, you could well have found it exhilarating. The daylight, the views of planes taking off and landing, and the scale, grace and power of the huge building itself, all contribute to that experience.

If, on the other hand, you had to spend hours waiting for your flight in a departures hall that was packed and fractious, no amount of daylight would have quelled the frustration. But then again, you may have looked up at that breathtaking roof, marvelled once more at the seemingly endless open spaces, and thought: “Well, Heathrow is Europe’s busiest airport, so it’s going to have the occasional flight delay, isn’t it …?”

The figures

The final analysis Terminal 5 cost £4.3bn and was developed over a period of 18-and-a-half years, including 10 years for the planning application and public inquiry. £1.4bn was spent on the construction of the building itself, which is the UK’s largest freestanding building at 396 × 176 × 40m – the size of 50 football pitches. It took 20,000 workers 37 million man hours to build and contains 30,000m2 of glass, 150,000 tonnes of steel reinforcement, 90,000 tonnes of structural steel, 1.2 million m3 of concrete and 2,300km of cabling. It will cater for 30 million passengers a year

Getting there

T5 comes with its own dedicated station of six platforms serving London Underground and the Heathrow Express from Paddington. You alight in a smart station that breaks the London Underground mould of gloomy tunnel platforms. It has plenty of headroom and daylight, as it is covered by a billowing roof of transparent ETFE. You park your luggage on a trolley and trundle it a few steps to a lift, which zaps you up five storeys to the top of the building on the fourth floor.

Alternatively, if you drive, you can park right next to the terminal. Some 3,800 car parking spaces have been stacked in a four-storey car park that stretches as long and nearly as high as the terminal. It’s no less grim than any other multistorey car park in the world, but at least you can quickly escape to the terminal along a sky bridge that traverses a deep, narrow canyon.

A real high-flier

There are many reasons why T5 can claim to be a cutting-edge airport terminal. In architectural terms, here are four important innovations that Rogers has introduced:

High-rise configuration

Whereas nearly all other airport terminals are one or two storeys, T5 has the relatively high-rise format of four public storeys above ground, as well as three service floors below ground. The 300,000m2 building was squeezed upwards by the need to fit between the airport’s two runways and the green belt beyond them.

Loose-fit shell

The shell of the building, along with all the columns and beams supporting it, is completely separate from the four floors of accommodation it encloses (see picture, far left). As well as providing open spaces all round the perimeter and across the top floor of the building, this has a practical long-term purpose: it provides the ultimate in flexibility, as the four floors can be completely demolished and rebuilt in a different configuration without touching the perimeter walls and roof. This flexibility promises to keep the building up to date with what Rogers’ director, Mike Davies, likes to call the “continuous churn” in high-speed travel, whether by air or land.

The roof

Arching gently overhead without any intervening columns, this 176 × 396m structure is supported on deep, curving steel girders. Towards the perimeter walls on either side, pairs of girders are picked up by four outstretched arms of tubular steel. These come together in a huge powerful steel knuckle set just above eye-level. Each knuckle stands on two splayed stilts that disappear down into the continuous perimeter void between

the glass wall and the edges of the floor slabs.

High-speed baggage handling

What BAA claims is the world’s most advanced baggage system is housed in a double-height basement floor. A robot automatically sorts up to 12,000 bags an hour. It then stores them until the flight is called or dispatches them to the appointed departure gate or other terminals at 10m/second in driverless rail wagons powered by linear induction. According to BAA, that should cut late bags to less than one in every thousand and help root out flight delays and cancellations.

Coming back

Obviously, on your return journey the aim is to get out of the building as quickly and painlessly as possible, so you probably won’t mind that your route is confined to the first and ground floors, which means you miss out on the building’s vaulted roof. The double-height baggage hall is no less impressive for that. This has a sharp and shiny ambience of stainless-steel columns, polished marble-composite floors and a ceiling made up of large white saucers. The 11 baggage carousels are in full view on the floor below as you enter, and you take an escalator down to pick up your cases. You’re now on the ground floor, so it’s just a few steps out to the other side of the building before you can truly appreciate being back in sunny Britain.

Project team

Client and construction manager BAA

Occupant BA

Architect Rogers Stirk Harbour & Partners

Structural engineer Arup

Civil engineer Mott MacDonald

Services engineers DSSR, Arup

Quantity surveyors Turner & Townsend/EC Harris

Executive architect Pascall + Watson

Retail architect Chapman Taylor

Station architect HOK International

PRincipal contractors Laing O'Rourke, Mace, Balfour Beatty, Amec

Downloads

The route through T5

Other, Size 0 kb

No comments yet