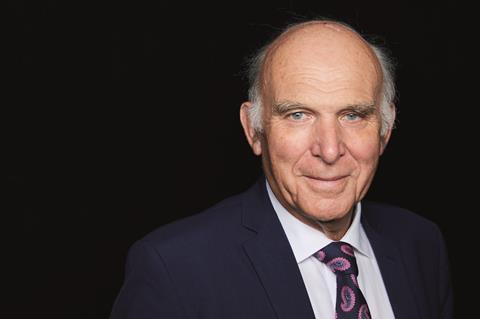

Vince Cable is in bullish form. As leader of the Liberal Democrats, the only party opposing Brexit, he believes he’s gaining ground on his two main rivals. But the 75-year-old parliamentary veteran is keen to show his isn’t a party campaigning on a single issue. Chloë McCulloch talks to him about his new housing policy, Heathrow’s third runway and Carillion’s ‘horrific’ collapse.

Outside Portcullis House it’s a hot, sticky day, with the traffic seemingly at a standstill, the Westminster pavements heaving with tourists and Brexit protesters holding up EU flags and placards. Vince Cable is running late – returning from Buckinghamshire where he has been addressing a UK-India trade conference. The photographer is worried he could arrive sweaty, so sets aside a packet of wet wipes and a glass of water just in case. But when Cable strolls into the air-conditioned meeting room overlooking the Houses of Parliament, he looks calm and composed, wearing a blue suit, crisp white shirt and paisley-patterned tie – not hot and bothered at all.

The 75-year-old Liberal Democrat leader is experiencing a late surge in his career. He is best known as the business secretary when his party was in coalition with the Conservatives. During this time, he gained a reputation for pragmatism over ideology and was generally respected by industry and politicians. All that came to an end in the 2015 general election, when the electorate turned on the Lib Dems and Cable lost the 12,000 majority in his south-west London seat of Twickenham. By his own account, the former chief economist for Shell spent the next two years writing books, travelling and ballroom dancing. Few expected him to contest his seat again, but in the 2017 snap general election he was back as an MP and, after Tim Farron’s resignation, became party leader last July.

If free movement is closed off, the construction industry is potentially in serious trouble

A position in government again may seem unlikely given his age and the fact that his party only has 12 MPs in the Commons, but his career to date shows he’s full of surprises and not a politician to underestimate. Moreover, the ups and downs of the Brexit saga – and the Tories’ lack of an overall majority – mean whispers of another snap election are quick to resurface. If that did happen, despite working from a low base, the Lib Dems would be in a good position to pick up discontented Remain voters.

And if Cable were to get back into government, he could arguably do quite a bit for construction. His time as business secretary, during which he led on the government’s Industrial Strategy, exposed him to the challenges facing the sector. He reels them off with ease: its failure to hit housing targets, the barriers to innovation, the drive for more offsite manufacturing and the need to improve skills and training. So, if in power once again, how would he help?

The green belt has become a kind of religion

He wouldn’t push ahead with Brexit – that’s for sure, he quips. But that aside, he and his team have spent several months coming up with a new housing policy, unveiled this week (see “Lib Dem housing policy”, opposite), containing detailed proposals he thinks would help rebalance the housing market, providing more council housing and more affordable homes for first-time buyers and key workers. In this interview, he talks about what makes his housing policy different from those of his rivals, the effect of Brexit on construction, lessons learned from Carillion’s collapse and what should be done to protect suppliers from big corporate failures in future.

Cable on …

Heathrow’s third runway

“I think there’s a legitimate set of questions about who’s actually going to pay for it. There are vast disparities between the cost estimates on the runway and on the infrastructure and, until that is clarified, it is very far from clear that we have a sensible, viable project.”

The £3.5bn parliament refurbishment

“I tend to be in favour of economical solutions and for having parliament rotated around provincial cities so that we turn this potentially very costly exercise into something positive for democracy. In Tudor times, monarchs used to go around the country and spend a few months in York and a few months in Lancaster. Maybe we should revive that model.”

The apprenticeship levy

“The original idea was that employers would be rewarded for training through levy abatement and that those who didn’t train would pay the levy. That hasn’t happened – in fact, good training companies are effectively paying twice. As far as we can see, training is falling off a cliff.”

The Brexit effect

On the morning he meets Building, tensions are running high in the Commons, with a key vote on the EU Withdrawal Bill hanging in the balance. No one is sure how many Tories will actually rebel over the question of parliamentary sovereignty in the hypothetical scenario that the negotiations with the EU end in no deal.

That afternoon, the rebellion turns out to be something of a damp squib, with the government winning, but Cable is clear that this is just one fight in the “battle for Brexit”.

As the Tories, and to some extent Labour, go through an existential crisis at each stage in the Brexit negotiations, the Liberal Democrats have been consistently pro-Remain, demanding a second referendum on the final Brexit deal.

A big part of Cable’s pitch is to offer a moderate middle-ground between prime minister Theresa May on the right and Labour’s Jeremy Corbyn on the left. So far he’s had some electoral success, with his party taking three councils from the Tories in the May local elections and increasing the Lib Dem share of the vote in the Lewisham East by-election this month, coming in second behind Labour.

For construction, which is dependent on the free movement of labour (especially London, as the latest Office for National Statistics figures show), he says the stakes could not be higher. “If [free movement] is closed off, the construction industry is potentially in serious trouble.” He also says construction will be particularly affected by a Brexit drag on the economy: “It affects general confidence levels in the economy. You can see that people are now reluctant to take on financial obligations they otherwise would, because they are uncertain about the long term.”

Building homes

While Cable’s views on Brexit are well known, his solutions for tackling the housing crisis are less so. This is something he and his party are looking to change – not surprisingly, given the importance voters attached to the issue in the last election. Cable’s diagnosis of housing’s malaise is nothing new. He points to the failing “developer-led model”, which he says “doesn’t work because land prices are too high and, by the time this is factored into the price of houses with the developers’ margin, they’re just unaffordable”.

Part of his solution is to create a government agency based on the model of new town corporations, which would have borrowing and compulsory purchase order (COP) powers. He says the statutory body would also need some form of local accountability, with perhaps council representation on the board. The government legislated last year for something similar, in the form of locally-led new town development corporations and COP reform, but Cable says the key difference is that the government did not tackle the thorny issue of land value.

The background to this is that the post-war new towns were able to buy land at agricultural prices and then keep hold of the uplift in value and reinvest it in local infrastructure. Today, however, new towns would have to pay full prices because the landowners can claim “hope value” on land that has no planning permission. Cable says: “We will have to change legislation […] under which the basis of compulsory purchase was changed so that the hope value was included in the compensation price. We just cannot continue with that system.”

Again, Cable is not alone is identifying hope value as a problem. He concedes that point, but says: “It’s fair to say that both Labour and the Conservative Party have nibbled around this subject without actually following it through.” This points to a growing political consensus emerging among the main political parties around the need to capture land value by one means or another.

Lib Dem housing policy

Greenbelt swapping

Freeing up disused parts of the green belt, such as former petrol station sites, for housing in exchange for protecting urban green space such as parks and playing fields

Development agency

An arm’s-length, not-for-profit agency with compulsory purchase powers that buys land at low cost. Land used for agriculture would be acquired minus the “hope value” that inflates prices, aiming to build houses at as low as 40% of market value

Public sector land

Big landowners such as the Ministry of Defence must release land for housing. Tough Treasury sanctions would be imposed for public sector land banking

Empty homes

Where the housing stock in areas of natural beauty and in London is unoccupied by non-resident owners, there would be greater sanctions such as increasing the 200% council tax on empty homes to 500%

Social housing

Of the 300,000 new homes that are needed a year, 50,000 should be for social housing. This would require removing the cap on local authority borrowing, giving councils discretion to curb the Right to Buy, and removing the affordable housing exemption for small developments

Wrangles over the green belt

Perhaps where there is some clear blue water between Lib Dem and Tory housing policy is over the green belt. The government’s housing white paper drew widespread criticism from the industry for not tackling the controversial issue of building homes on greenbelt land, with many blaming their fear of upsetting the blue vote in the shires. Cable says the popularity of the green belt is a problem: “Politicians are reluctant to tamper with it, but tampering with

it is exactly what we need.” And he’s quick to put the boot into his former coalition colleagues: “I was in the government when this issue was confronted and, at the insistence of the Conservative secretary of state [Eric Pickles], they just simply closed down the issue.”

The green belt, he goes on, has become “a kind of religion” and, with nowhere else to go, development starts to encroach on valuable green space in cities, such as playing fields. Cable’s party is proposing land swaps: “Where greenbelt land doesn’t serve an important utility function, it should be open to development and compensated by land elsewhere.”

He clarifies that this would mean introducing different categories of greenbelt land, with some having lower protections, as opposed to the green belt’s protection being reduced overall. He won’t be drawn on how these types of land would be defined except to say they will be semi-developed, poor-quality or industrial areas. However, if such a policy were to get picked up by the next government, of whatever political hue, the legal drafting of such a definition would be fiercely fought over and massively controversial.

Other housing measures include freeing councils to develop their own provision and expanding the Rent to Buy model, which he says Eastleigh council is promoting, so that household rents add up to eventual home ownership.

Of Help to Buy, he is scathing, saying it’s “completely the opposite of what the phrase implies” and so he would scrap it. Right to Buy he doesn’t approve of because it has reduced the pool of council housing, but he would leave it up to councils’ discretion to continue it. He would also look to break up the market dominance of volume housebuilders “because at the moment the smaller builders are being squeezed out”. And, on council estate regeneration with joint ventures, he points to Lib Dem councillors in Haringey backing the Momentum group’s opposition to the Lendlease deal, saying: “A lot of these urban regeneration schemes have been very damaging. They may have made money for the council but they have been damaging for the social mix.”

Corporate failure

While Cable takes a strong stance against private sector involvement in this context, his views are more nuanced when it comes to corporate entities taking on other types of public work. He describes the failures of Carillion as “a horrific story” but says “there is a fundamentally difficult problem because many of the tasks of constructing, say, complex new hospitals or whatever can’t be done by government – they have to be done on a contract basis. But the Carillion case showed a lot of weaknesses in the existing system.” One of the weaknesses he identifies is the civil service, where he says people are not sufficiently trained to manage complex negotiations. Civil servants, he says, need to be able to negotiate contracts that don’t squeeze contractors to the point where they topple over, but also are not so generous they are accused of “padding out the profits of companies”.

He also wants to see more protection for the supply chain from upstream insolvencies, saying many suppliers “are essentially being used as a kind of piggy bank by the contractors”. He admits that measures taken when he was in power to ensure proper credit terms for suppliers probably didn’t go far enough, and that now there needs to be action to ensure they are paid. Ultimately, he says: “The sanction is if companies behave badly to their supply chain companies they don’t get future contracts.”

Cable clearly has doubts over construction’s health and prospects. By contrast, he is upbeat about his own party’s future. His parting words are about how the Lib Dems have “turned a corner and are working our way back in different parts of the country”. He reckons that by next May they will have control over “a significantly large number of local councils”. By then the UK is due to be out of the EU, with who knows how many political casualties before it gets there. For Cable, there’s everything to play for.

No comments yet