Qatar is one of the richest countries in the world and with the 2022 World Cup and its national development plan there’s plenty of work around. But how easy is it for Western firms to access the construction opportunities? And are they really up for working in temperatures of 50°C?

Doha is a city of flash cars, jet-skiing sheikhs, lavish all-day brunches at grand hotels and glistening towers. And it is also a city of forced labour, shanty accommodation crammed with migrants, back-breaking construction work and human rights abuses. Then every shade in between.

Qatar shot to prominence when, a year after gaining independence from the British Empire, it discovered the world’s largest gas field in 1972, propelling it from quaint obscurity to the frontline of the Middle Eastern energy boom. Its population has also ballooned from 100,000 in 1970 to over 2.2 million.

Yet many people have only heard of Qatar today because it sensationally won the right to host the 2022 football World Cup. It begged the question - how could such a tiny country, with virtually no history of the game, a chequered human rights record, and intolerable summer temperatures of 50°C-plus pull off such a feat? The improbable result helped spark corruption investigations into football governing body FIFA by British newspapers, Swiss prosecutors and the FBI. Yet despite a whirl of allegations against Qatar’s World Cup bid, ultimately it was unrelated historic misdemeanours that claimed the jobs of football bosses Sepp Blatter and Michel Platini. Meanwhile, Qatar retained the tournament, like a skilled footballer keeping the ball through a flurry of tackles.

But in the UK it seems public opinion is already set - Qatar is the bewildering, almost ridiculous host of the world’s best-loved sporting tournament. And, what’s worse, it’s widely presumed hundreds of migrant workers will die building the stadiums where it will be played, despite there being no reported deaths on World Cup projects to date.

Without apologising for Qatar - its problems are indeed many and varied - there is inevitably more to the country than this. Building has visited Qatar twice in 18 months to cover preparations for the World Cup and to find out what construction professionals make of life in one of the world’s fastest-growing countries.

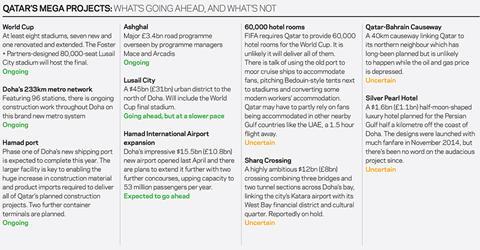

Because for Qatar’s construction market, it’s crunch time. The country has barely begun constructing the £3bn-worth of World Cup stadiums needed, and other hugely ambitious projects are in the pipeline, from completing Doha’s 232km new metro system to delivering the $45bn city district of Lusail, the planned backdrop for the World Cup final. All this when Qatar, like its Gulf neighbours, has been rocked by the global slump in oil and gas prices, forcing it to rein in spending and axe some projects. Many UK firms have carved out success in Qatar - including Zaha Hadid Architects, Arup and Interserve - but some have come and gone, such as Gardiner & Theobald, Laing O’Rourke and Galliford Try. The Brits still in Qatar readily admit it is no cakewalk.

So in the face of its challenges is Qatar likely to be ready to host the 2022 World Cup? And how are UK firms withstanding the heat in this ultra-competitive market?

Building towards 2022

Qataris balk at any attempt to reduce their country’s ambitions to hosting a single tournament, and rightly so. The country is also investing heavily in other areas of its economy, including education, healthcare, manufacturing and services. It also has big cultural ambitions, with majestic new museums like the Jean Nouvel-designed National Museum, inspired by the scattered petals of a desert rose, taking shape in the city. It may not be a tourist hotspot now, but parts of Doha are also surprisingly vibrant, with a cosmopolitan food and art scene in the bustling, rebuilt old town souk. The Qatar National Vision strategy sets out an ambition to establish an economy no longer dependant on oil and gas exports by 2030.

Nonetheless experts predict the World Cup will be the biggest driver of Qatar’s construction sector over the coming years, whether it be stadiums or the supporting infrastructure necessary to host the tournament. That includes roads, metro links, airport expansion, port expansion and “overlay” work like fan zones, media facilities and security. Global Construction Perspectives and Oxford Economics forecast Qatar’s construction sector will grow by an average of 12.1% per year up to 2020 as a lot of this World Cup-related work is delivered, before slowing to 3% per year over the first half of the 2020s and to 0.7% per year thereafter. By 2030 the Qatari construction sector will be worth £44bn, more than double its value of £20bn in 2014.

Despite these strong forecasts, many firms on the ground point to a significant slowdown in Qatar in recent months due to the oil and gas price slump. Many UK firms have established a presence in Qatar, not least British consultants and architects, who arguably out-punch any other foreign nation - Foster + Partners, Zaha Hadid Architects, Mace, Gleeds, Rider Levett Bucknall (RLB), Turner & Townsend, Arup and Hilson Moran are among them - while the two chief British contractors are Interserve and Carillion. Also, the UK businesses of major international firms like CH2M, Aecom and Arcadis have a presence in Qatar. Both Brits and non-Brits say the market is proving tough at the moment. Not all are willing to speak on the record, citing Qatari client sensitivity to the press.

“It’s a tricky market at the moment,” one Brit tells Building. “It was an architects’ playground at one point, but now there are massive cutbacks.” A consultant concurs: “Most budgets have been reviewed. There are not enough projects around for the number of consultants and I don’t see much movement for another 12 months.”

Some firms can see the positive side of the slowdown as Qatar has been given a reality check. “Qatari clients are taking a long hard look at what they’re investing in and why,” says Sam Graham, Qatar-based director at RLB. “They’re focusing on those that provide some kind of economic payback going forward.” There’s also now talk of Qatar diversifying its income by introducing taxes such as VAT for the first time and exploring funding options like public private partnerships.

The consensus is that the slowdown has hit mid-size projects hardest. Few believe the country’s ability to host the 2022 World Cup has been threatened, although there are serious question marks over aspects of the plans. Nonetheless, when it comes to the actual World Cup programme, some are concerned that despite Qatar’s best intentions to be a good client, its inexperience could be costly.

“Qatar is in the process of procuring an infrastructure programme worth in excess of $250bn. There is massive ambition to deliver this successfully but few countries have experienced such a pace of change and sometimes lack of client procurement experience can lead to delays and uncertainty,” says one source. “The programme’s got to accelerate or we’ll have too much happening at the same time. Energy prices are causing a pause and if it persists there’s going to be a mad rush to meet World Cup deadlines. In turn that could stoke construction cost inflation.”

Withstanding the heat

While there are lots of exciting work opportunities in Qatar, there are also a lot of potential pitfalls. Finding a suitable local partner, the long slog of getting established, and managing risk on hellishly onerous contracts are just some of the challenges.

Picking the right local partner is cited as key by many working in Qatar. While it is possible to work on individual projects without incorporating in Qatar, it is highly recommended for anyone serious about getting established. All companies in Qatar have to be majority owned by a Qatari, so typically the ownership is split 51:49, with the international firm taking the smaller share. Some Qataris’ involvement is limited to just that, and perhaps their name on a plaque in the office.

But some Brits cannot sing the praises of their Qatari partner enough. One British firm says: “An active partner is essential. It’s effective when you need it - if you need visas speeding up, or ports unblocking, or to get through some bureaucracy.” The Qatari government is effectively run by an opaque network of families and connections, ultimately led by the ruling Al Thani family, and it pays to partner with someone as high up the food chain as possible.

But, once you’re set up, don’t expect quick results. “There’s still a lot of the ‘fly in and fly out’ approach but that never works,” says Matthew Kitson, Qatar regional director at Hilson Moran. “You need to fully commit. People often expect to get results within six months, but it can take a year or more.”

A further potential barrier to entry is the Qataris’ renewed enthusiasm for applying a long-standing law which requires all construction firms to be “Grade A” qualified to work on public projects, a qualification that can take two years to obtain based on a range of financial and technical criteria.

The contracts in Qatar can be horrendous. As one market source puts it: “They are not transparent, variations are not permissible, it’s a fixed price, there are punitive liquidated damages and massive liabilities.”

Take it from a lawyer, Pinsent Mason’s Peter Blackmore: “I think a lot of contractors new to this market underestimate the contracts and are naive in relation to change and the claims process. Consequently on project after project in Qatar there are unresolved issues around claims on scope.”

But for those who persevere, many ex-pats are enjoying life in Qatar. “The culture is good, the Qataris have a lot of respect for people and families,” says Hilson Moran’s Kitson. “It’s an exciting challenge professionally and it’s a great life for me and my family.” Meanwhile, Gleeds’ associate director Grant McIntosh’s advice is to come to Qatar with an open mind. “Leave everything you know at Heathrow Airport. Come here with a blank canvas. Embrace the traditions and learn how things work. If you come with preconceptions you’ll fail.”

Keeping cool at the World Cup

Matthew Kitson, Qatar regional director at M&E engineer Hilson Moran, is also player-coach for an amateur football team in Doha that meets to play every week without fail, even through the searing hot Qatari summer. “It’s a little bit hot,” he says with some understatement of the possible 50°C-plus temperatures, “but you just stop for water every 10 minutes. We play in the evening, out of direct sunlight. I never bought the arguments that you couldn’t host the World Cup here in summer.”

Kitson isn’t the first British engineer to advance this argument in Doha. One of the ironies of Fifa bowing to international pressure, including from the UK, to move the tournament from summer to winter was that many British engineers were champing at the bit to prove the cooling technology existed to make a summer tournament possible, even if teams were not as happy as Kitson’s amateurs to brave the heat. Zaha Hadid and Aecom’s Al Wakrah stadium, for instance, featured air-conditioning and clever aerodynamics and shading that they claimed would make summer matches possible. Air-conditioned training stadiums and trial fan zones have already been successfully delivered.

“It’s not difficult to keep a stadium bowl cool,” Kitson says, describing the technology. “Hot air rises and cold air sinks. What’s important is managing the influences of air flow through the stadium.” As it happens, the stadiums are all still being designed with hi-tech cooling in them to allow them to be used in summer in legacy mode, albeit with half the seats stripped out. Kitson adds: “I’m absolutely convinced they’re going to work.”

Be that as it may, the World Cup is now going to be played over 28 days in winter, with the final played on

18 December 2022.

No comments yet