Last month’s by-election defeat saw Tory fears about the political impact of widespread planning reforms become a reality. The government now has little choice other than to water them down

Last month’s by-election in Chesham and Amersham could easily become a defining moment for the government’s increasingly controversial attempts to reform the planning system.

This is because planning became arguably the most significant issue behind the stunning victory of the Liberal Democrat challenger Sarah Green. The Conservative Party’s shock defeat has therefore piled huge pressure on the government – not least from its own backbenchers – to abandon the reform programme set out in last year’s white paper, which proposed the introduction of a form of zonal planning, binding centrally-set housing targets, and the ditching of Section 106.

Already the rhetoric has shifted profoundly. Where the prime minister talked last year about “levelling the foundations and building, from the ground up, a whole new planning system”, last week the housing secretary told councils that “I don’t think we need to rip up the planning system and start again”. The real question is what this about-turn in messaging actually means in terms of the substantive reforms proposed.

Bad faith

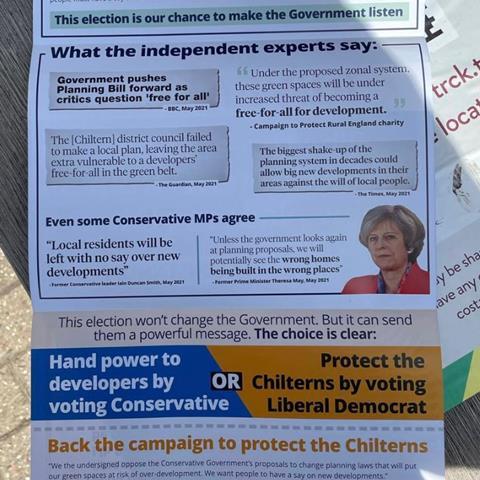

It is no surprise that the Conservatives are concerned about the political impact of the plans. In Chesham and Amersham, Lib Dem campaign leaflets ruthlessly used quotes from two former Tory leaders Theresa May – saying proposed reforms would see “the wrong homes being built in the wrong places” – and Iain Duncan Smith – saying “local residents will be left with no say over future developments” – to whip up concern over the government’s reform plans.

Never mind that the Chesham and Amersham constituency, residing both in the metropolitan green belt and in an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, is probably one of the most protected places in the country from development. Or that, under the proposed reforms – as the Lib Dems I’m sure knew well – it would remain so. The point is that the win gave the party’s leader, Ed Davey – someone who a few weeks ago could not buy a slot on local radio – the national spotlight in which to opine that between 30 and 40 safe southern Tory seats were within his party’s grasp. If true, this equates to a veritable blue wall of Conservative shire constituencies at risk. Griping about Lib Dem bad faith misses the political significance of the moment.

Likewise, it is a waste of time trying to divine the exact extent to which planning, versus HS2, the mishandling of parts of the pandemic, Tory sleaze and latent southern remainer animus towards the current prime minister contributed to the defeat. As Chris Rumfitt, seasoned political observer and co-founder of public affairs group Field Consulting, says: “It’s impossible to know how big a factor it was. The point is that those opposed to planning reform will jump on this – and they already have done.”

Hugh Ellis, director of policy at the Town and Country Planning Association and an opponent of the government’s plans, says: “Make no mistake – the politics of planning are 100% different to where they were before Chesham and Amersham.”

With William Hague, another former Conservative Party leader, warning that the reforms could be “Boris Johnson’s poll tax”, Rumfitt says there is now a “grave risk” to the reforms coming forward at all. Of course this leaves the government in a bind.

Just over two months ago it made planning reform the centrepiece of its Queen’s Speech, using briefings to national newspapers to frame it as part of its commitment to “levelling up” the Midlands and the North, and enhancing its appeal to so-called “red-wall” voters who have been locked out of the housing market. The reforms have also been presented as part of the UK’s plan to “build back better” following the pandemic by unleashing a surge of economic growth.

The government cannot just ditch them entirely. Rumfitt says it is ultimately likely that “dropping it all now is just too politically embarrassing”. He – and most other observers of the process – now see a significant dilution of the government’s plans as the most likely outcome of this political upheaval. So, what specifically could that entail?

Automatic permission at risk

The most obviously controversial part of the white paper reforms is the commitment to zonal planning. The idea was that councils will have to zone a proportion of their land for “growth”, and that by doing so they will confer automatic outline permission on it – meaning residents would be unable to object in principle to individual applications coming forward.

This supposed democratic deficit has been at the heart of objections by local government, the CPRE and Tory MPs to the reforms, with influential backbencher Bob Seely accusing the government of “stripping away democracy”, and former planning minister Bob Neill warning that the changes should not come “at the expense of local democracy”.

One director at a think-tank influential in Tory circles says the conferring of outline planning permission via local plans – in his view the one major innovation contained in the proposed reforms – is clearly at risk. “There are lots of things in the reforms like digital planning where there is broad consensus, and they will go through with that. But I would not be surprised if they drop the plan to stop people objecting to individual applications.”

This does not mean that zonal planning will entirely be dropped, he says – simply the white paper’s idea that those areas zoned for growth in local plans will benefit from automatic outline permission. “Zones will be kept, but it’s most likely they won’t keep the bit where you get automatic outline permission.”

Another option, Rumfitt says, would be to keep the idea, but restrict it geographically to very specific areas, such as development corporations or freeports.

It is not only this proposal that is now under threat. The Times newspaper has reported that the government is considering dropping its proposal to set “binding” housing targets on local authorities. In the light of the almighty fuss caused by the so-called “mutant algorithm” last autumn, on which the government was forced to back down, this is hardly surprising.

That rebellion came about despite the fact that the numbers produced by the algorithm were not binding on councils, while this further proposal, put forward in vague terms in the consultation, will mandate specific numbers, and thereby surely provoke even greater howls of outrage once more detail is handed down.

Developer levy to be locally set

The other really big reform contained in the white paper is around developer contributions, where it proposed virtually scrapping the Section 106 system, and replacing it with a flat rate developer levy to pay for necessary affordable housing and local infrastructure. This is less politically controversial, but divides opinion in the industry itself.

While some welcome the idea of an end to protracted Section 106 negotiations, others are concerned about the impact on site viability, and the ability to deliver mixed communities including both market and affordable housing – one of the great successes of the UK system.

Most observers suggest that ministers remain set on this reform in principle – despite the difficulties of drawing up a workable system in practice. The idea of a nationally-set flat rate levy has been dismissed by almost everyone in the sector as unworkable – penalising the least viable brownfield sites, which are exactly the ones the the government says it wants development to come forward on.

In fact, Jenrick last week signalled that this change is already coming. In a speech to the Local Government Association, he said the tariff was now intended to be “locally set” and “locally levied”, with greater flexibility for councils to determine how they are spent. However, without the simplicity of a single, national levy, the policy could end up mired in exactly the same complexity and confusion that has dogged the existing Community Infrastructure Levy – the last attempt to “replace” Section 106.

With observers expecting the government to finally respond to the white paper consultation in the autumn, prior to publication of a bill either later this year or early next, we will find out more about the direction of travel in the next couple of months.

And, with Chesham and Amersham putting planning reform firmly in the realm of high politics, ministers have some tricky decisions to make, meaning developers would be wise to take heed of Jenrick’s recent comments, and not expect the root-and-branch reform of the system they were promised last year.

Then Boris Johnson said that this was the moment for the most significant reform of the planning process since its creation in 1948. The likelihood of that now? “Not a chance,” says Rumfitt.

No comments yet