The construction industry has made huge progress on on-site safety in the last 20 years but health conditions have largely been neglected. Are things starting to change?

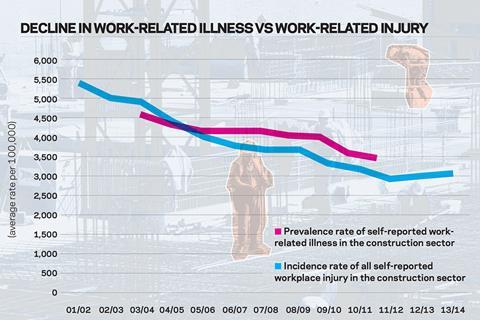

It’s fair to say occupational health has taken a backseat to the more dramatic issue of accidents and injuries in the construction industry over the years, with big improvements in the incidence of site fatalities in the last

two decades.

However, increasingly this focus is being questioned. Why? Heather Bryant, UK health and safety director at Balfour Beatty, makes it clear. “Construction workers are 100 times more likely to die from occupational diseases and ill health than they are from poor safety,” she says, referencing historic Health and Safety Executive (HSE) data that points to an excess of 5,000 deaths per year, mainly from past exposure to cancer-causing materials such as asbestos.

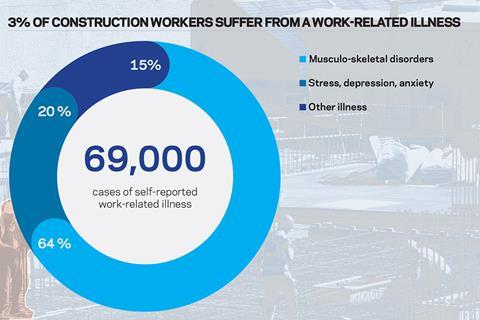

But it is not just the tragic overhang of the previous generation’s ignorance of the harm caused by asbestos and other carcinogens that is causing concern. In Great Britain, between 2011/12 and 2014/15, 69,000 (3.1%) workers per year in the construction industry were suffering from an illness they believed was caused or made worse by their work, according to data from the HSE, the only body collecting data in this area.

Around 45,000 of these cases were musculoskeletal disorders (MSD) such as back pain or limb injuries, of which just under a third were new conditions. Meanwhile, 14,000 were cases of stress, depression or anxiety, and 10,000 were other illnesses such as skin or respiratory conditions, of which 40% were new conditions. Of these 69,000 cases, 25,000 were from workers in the construction of buildings, 9,000 were workers in civil engineering and 36,000 were from workers in specialised construction activities such as demolition, plastering and painting.

The occupational health issues facing the industry are “huge”, says Paul Haxell chair of the construction group at the Institution of Occupational Safety and Health (IOSH). “Historically we have had a very strong emphasis on safety, but not always managed the same level of control around occupational health,” he says.

Finally, however, it seems this approach might be changing. A group of leading industry players has got together to put on the inaugural Construction Health Summit in London next week, which will aim to address the lack of leadership on occupational health in the industry. But can it really make a difference?

Defining the issues

Occupational health is an overarching banner covering a wide variety of issues from fatal cancers, to MSD, deafness, anxiety and dermatitis - with symptoms of many of these illnesses not becoming visible for years.

This delayed impact is one of the reasons IOSH’s Haxell believes the industry hasn’t been as responsive as it should have been to the occupational health challenge because “it doesn’t manifest itself in the here and now”.

This imbalance has also partly been because firms have “always seen safety as their number one priority because they see the accidents statistics and how much it costs them when an accident occurs,” says Jennie Armstrong, occupational health lead at Mace. Hence companies have not historically invested in occupational health.

But the lack of focus is also because occupational health issues are harder to quantify, as Build UK chief executive Suzannah Nichol says: “The industry recognises it needs to take health as seriously as it takes safety, but it is always a bit more difficult to understand and tackle health issues because safety is more visible - you notice when things are wrong and you can put them right.”

Construction, according to the HSE, has the largest burden of occupational cancer among the industrial sectors, accounting for 40% of occupational cancer deaths and cancer registrations the last time it was calculated in 2005. That there has been no new data in this important area shows what a relatively low profile it has had. It was then estimated that past exposure annually causes over 5,000 occupational cancer cases and 3,700 deaths

in the industry. Of these 70% are caused by asbestos, 17% silica, and 6-7% diesel engine exhaust.

In 2004 the industry also had the highest number of cancer registrations, at 5,400, which like the death rate were predominantly caused by past exposure - 2,800 from asbestos, 800 from coal tars and pitches, 700 from silica and solar radiation.

Meanwhile stress and MSD, for which there is data up to 2014/15, on average account for 85% of work-related illness cases in the sector.

The HSE reports that the rate of work-related MSD in the construction sector is almost twice the rate across all other industries, according to data from the GP reporting scheme.

It finds 2% of construction workers annually are suffering from MSD they believe is work-related, nearly 50% higher than the 1.3% rate across all industries. The rate of those working in skilled construction and trades is even worse, standing at 3% - more than twice that of the general UK workforce.

The industry also has the highest estimated rates of back injuries and upper limb disorders, as well as the highest rates of ill health from noise and vibration-related conditions, such as hand arm vibration.

Annually around 3,000 construction workers between 2007/08 and 2014/15 have suffered with “breathing and lung problems” they believed were work-related or made worse by their work. Nearly 20% of those workers reporting work-related respiratory problems identified “dusts from stone, cement, bricks and concrete” as contributing to their condition.

This avalanche of data makes clear the extent of the problem. The only relatively bright spot is that the rate of construction workers suffering from stress, depression or anxiety was 0.7 percentage points less than the rate across all industries, which stands at 1.3%, according to the HSE’s GP reporting scheme data.

Adding up the cost

The immediate impact of occupational injuries or illnesses on a business can be seen in the lost working time due to absence. The HSE estimates that 1.7 million full working days were lost in the construction sector during 2014/15. Of these, 1.2 million were due to work-related illness, compared to 500,000 to workplace injury. This equates to 7,000 full-time workers being absent from the workforce for the whole year (225 day year) in the industry.

The economic knock-on effect for 2013/14 is estimated to be £900m - £400m for illness and £500m for injury - accounting for 7% of the total cost across all industries - £14.3bn.

“There is absolutely no doubt there is a cost associated with health in the same way as there is with safety - people do have to have time off work if they have a really serious health issue,” Balfour Beatty’s Bryant says. “Clearly there is a health cost and a significant health cost.

“If anyone thinks that they can save money by saving on health and safety, then that is a false economy,” she adds.

If anyone thinks that they can save money by saving on health and safety then that is a false economy

Heather Bryant, Balfour Beatty

However, Mace’s Armstrong says that a lot of workers still come to work with ill health issues as they don’t always get paid if they take time off.

This means that the absentee data potentially under-represents the problem. “[Workers are] not actually performing as well as they could because of the ill health issues they’re suffering with. You tend to find a lot of people who are still at work, but can’t achieve what they need to do. So I think it does have a significant cost on production - as well as on people’s lives,” Armstrong says.

Transient workforce

One of the reasons for the lack of a co-ordinated effort around occupational health within the construction industry is the transient nature of the workforce.

“People move around from job to job so you don’t get that consistency and you don’t get to follow people and understand how they respond to each of their particular job roles as well,” says Armstrong.

This was one of issues that the Constructing Better Health (CBH) scheme, aimed to resolve as part of its goal of helping the industry achieve a fit and healthy workforce. The non-profit national scheme requires individual workers to carry a “workplace health fitness for task” CBH card, demonstrating that they are fit for the task they have been assigned.

The card means an individual’s health records stay with them, via a unique number identifying the individual’s records held on the CBH database. These records are obtained from an Occupational Health Service Provider which holds records created from health checks. Employers are then able to check that any employee has attended their health check, what type of health check has been carried out and any recommendations made to further protect the employee’s health. The information can also be accessed through a CSCS smartcard.

However, the scheme - which Armstrong considers “a good initiative” and has been mandated by clients such as Crossrail on their sites - is not seen to have gained much traction within the industry.

“People have been concerned because there is a significant amount of administration that goes with it…and the cost of it is quite expensive,” Armstrong says. Membership of the CBH scheme for a company is based on turnover so if a company has turnover of above £500m it can expect to pay fees of £10,275.

Haxell says it is not just the transient workforce that makes writing an industry-level policy on occupational health “quite a difficult document” to draw up, adding it is the fact you are dealing with a long supply chain and various sub sections within the industry where “not one size fits all”.

Armstrong agrees that the structure of the construction industry with its extensive supply chain and subcontracted work makes it more difficult as “you can lose control over what happens at each level of the tiers”.

Another problem in tackling occupational health is that most health issues have long-term effects so any illness or disease may not appear immediately.

“It’s unlikely that you’re going to get many health problems the following day - it’s 10 years down the line. So again it’s another challenge for us to manage as people don’t see the here and now effects that it has,” Armstrong says.

The construction environment has also not always been sympathetic to workers who raise concerns. According to Susan Murray, Unite’s national health and safety adviser, there were examples of that in the blacklisting scandal.

“People were victimised for doing just that [raising concerns],” she adds, saying it is why Unite is campaigning for “a working environment on all construction sites that allows workers to raise concerns without fear of victimisation”.

There has been a general lack of awareness, according to Haxell, and up to now there have been lots of medical checks done which he says only provide information as to how badly a construction worker’s health is deteriorating, rather than attempt to prevent problems arising in the first place. Yet, he adds that “people have now wised up that it’s about ill health prevention not just about measuring the level of deterioration.”

Joined-up thinking

The HSE has reported that while the construction industry has in recent years made “big improvements”, it is still a “high-risk” industry for health issues and injuries.

There are numerous initiatives, such as IOSH’s “No Time to Lose” campaign for cancer and the Considerate Constructors Scheme’s “Spotlight on …” strategy, and most firms have their own health and safety policies.

Balfour Beatty, for example, carries out a number of activities on a selected health topic with its whole workforce every quarter - direct employees and subcontractors - including showing videos of real life stories to help get the message across. The firm’s focus is on providing the tools for its employees to “look at how they can design out health risks” Bryant says.

For example, she says: “You may have something that historically caused hand arm vibration … So we [Balfour Beatty] will now look to see if we can use robot control devices so that there is no physical contact between the operator and the job that they are doing.”

Mace, meanwhile, has developed a five year strategy for tackling occupational health issues affecting its employees, projects and supply chain. Armstrong says the company is currently focusing on the standards it sets and how it manages health hazards in its construction activities. She adds that Mace is also looking at lifestyle factors including diet and nutrition, because having people who feel valued and are healthy has added benefits for the firm.

A lot more is going to get made of demonstrating the workplace is managed so workers are not exposed to hazards

Paul Haxell, IOSH

Edward Hardy, chief executive of the Considerate Constructors Scheme, says he recently visited a site and found it to have not only a restaurant providing a variety of food options, but a gym next door and was “proactively promoting the benefits of a healthy lifestyle to their workforce”.

However, these are disconnected schemes. Bryant admits that, saying: “I don’t think we’ve got all of the answers, but this is part of what the summit and working together as an industry will seek to achieve in terms of addressing health risks for the future.”

Many in the sector say the biggest missing element is in the leadership needed to bring together these disparate initiatives into something more substantial. Nichol sees the upcoming summit as “a real opportunity” for the industry to decide what it wants to do - whether it does the legal minimum or gets together to “find a system that ensures we positively manage people’s health”.

“A healthy workforce has to be better for everybody … Our industry works well when it has a clearly defined system - and we don’t have one at the moment,” she adds.

Haxell believes the renewed recognition of the seriousness of occupational health will produce an emphasis on managing exposure or preventing problems rather than monitoring deterioration.

“A lot more is going to get made of demonstrating the workplace is managed so workers are not exposed to hazards,” he says.

So there is still a huge challenge facing the industry and much work to be done to improve occupational health, particularly as hazards such as asbestos - which is still regularly encountered in buildings during refurbishment, demolition and maintenance works - silica, diesel exhaust fumes and the dynamic nature if the work mean construction will always have the potential to be damaging to health if risks aren’t managed.

It remains to be seen whether the Construction Health Summit will achieve a clear agreement on an industry-wide route forward for occupational health. But as Hardy says: “Occupational health can always be better and the construction industry can do a lot more.”

No comments yet