The Hinkley Point C nuclear power plant is edging closer to reality, with backing from China. But the nearer it gets to going ahead, the greater the opposition gathering against it. Can the industry finally start believing it will happen?

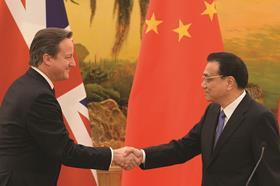

George Osborne was in China last month, banging the drum for British business. The chancellor of the exchequer’s agenda will have included putting the finishing touches to the long-awaited deal between French power company EDF and the country’s nuclear corporations to finance the first of a new wave of nuclear power stations.

The final sign off for the project, which is due to be built on the remote Somerset headland of Hinkley Point, is scheduled to take place when the Chinese president Xi Jinping makes his first state visit to the UK later this month.

Expectations that the long-delayed project might be finally achieving financial close intensified last month when Osborne told the House of Lords’ economic affairs committee that he was “pretty confident” that the deal, under which the two Chinese companies - China General Nuclear (CGN) and China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC) - will invest up to 40% of the £24.5bn funding, will happen.

Osborne supplied a further confidence boost by announcing on the China trip that the government would provide a £2bn guarantee for the project - the first of three plants to be developed at Hinkley, by the partnership led by French energy company EDF. On the same trip, recently appointed energy secretary Amber Rudd briefed that the project’s Chinese partners would have the opportunity to lead on the development of two new plants planned at Bradwell in Essex.

Alistair Smith, chairman of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers’ (IME) power division, says he is now “pretty sure that [Hinkley] is going to go ahead”.

“George Osborne’s statement is as positive as anything you get out of the Treasury,” he added.

However, progress has been slow since January 2008 when the last Labour government published a white paper backing the construction of a new generation of nuclear power stations (see timeline below). “It’s taken nearly eight years to get where we are on a single new plant,” says Malcolm Grimston, senior research fellow at the Centre for Environmental Policy, Imperial College, London. But even this close to sign-off, the latest diplomatic push masks the fact there are still significant doubts about it going ahead.

White elephant in the room

The go-ahead for the 3.2GW Hinkley C, if and when it is given, will still depend on the decision of a financially-challenged EDF, which has seen its share price fall by 40% in the last year. Meanwhile disquiet about the costs of the project and its technical feasibility mean the scheme, which has previously been given cross-party support, is attracting increasingly influential opponents.

Former cabinet secretary Lord Turnbull encapsulated these concerns when he told Osborne that Hinkley C, which is meant to supply 7% of the UK’s electricity needs when it is finally built, was a “white elephant” at the Lords economic affairs committee hearing. The new leader of the Labour party, Jeremy Corbyn, set himself clearly against new nuclear build in his leadership campaign.

As Ian Fells, emeritus professor of energy conversion at Newcastle University, says, all the government support can’t mask the fact that the Hinkley project is in “something of a pickle.”

This is principally because EDF’s planned nuclear plant at Flamanville in Normandy, which Hinkley is modelled on, is already six years behind schedule. In April, it emerged that the French nuclear inspectorate has concerns about the steel casing built to house the plant’s reactor. This is being supplied by the largely French state-owned company Areva which is also providing EDF’s reactor at Hinkley. Fells suspects the Flamanville casing will have to be replaced. At Hinkley itself, preparatory work had to be suspended earlier this year.

Mike Childs, head of policy at Friends of the Earth, believes that Hinkley will happen because of the political capital invested in the project so far. “It would be a massive political embarrassment if it fell apart so the government will do their utmost to make sure that it gets built,” he says.

But he predicts that the wider programme, which includes the other two plants at Hinkley and plants in Cumbria and Anglesey, will suffer a similar fate to plans by Margaret Thatcher’s government in the 1980s. Grand plans then for 10 new nuclear plants ended up with the construction of a single one at Sizewell B in East Anglia, which was only approved after a gruelling four year-long public inquiry.

However, Keith Parker, chief executive of the Nuclear Industry Association, puts faith in the government’s commitment to the wider nuclear programme.

Following a recent meeting with Rudd, he detects “no wavering at ministerial level” on the issue, despite rumours that Treasury officials share their former boss Turnbull’s cost concerns about nuclear. “They recognise that the nuclear component in the energy mix is very important moving forward,” he says.

When the lights go out

A look at recently published National Grid figures explains why the government is keen. These show that at times of maximum demand, the grid has a spare capacity of just 1.2%. Fells says this figure is “unbelievably small”, compared to the 15% spare capacity traditionally deemed necessary to ensure a secure energy supply.

A report published by investment bank Jefferies last week calculated that by next year the UK’s generating capacity of 53GW will be insufficient to meet peak time demand of 56GW.

“You only need one power station to fall over and you are in serious trouble,” says Fells.

One “common cause” failure across several plants, such as a type of boiler cracking or nuclear core degrading faster than expected, would pose even more serious headaches, warns the IME’s Smith, whose day job is nuclear development director for Costain. He adds that the UK benefits from much of its generation capacity working long after it was due to be phased out. And the crunch will intensify rapidly as a swath of polluting coal and aging nuclear plants close down over the next decade.

All but one of the current fleet of the atomic reactors, which generate nearly one-fifth of the nation’s electricity, are scheduled to be retired by 2023. Grimston estimates that this looming round of closures will remove around 10GW of generating capacity.

Unless work starts on new nuclear plants soon, the only way to plug the gap will be to build gas-fired plants, leaving the UK reliant on unstable or downright hostile regimes in north Africa and Russia, says Smith, who says that “being at the whims of Mr Putin would be a very dangerous thing”.

The problem with renewable energy meanwhile is that until more effective batteries are developed to store electricity, the power produced by this low-carbon alternative to nuclear is inherently intermittent.

The nightmare for energy planners is cold and calm winter nights when everybody wants to use electricity but the sun is down and there is hardly any wind. Increased renewable generation must therefore go hand in hand with new back-up gas-fired plants to pick up the slack.

But countering all of this accepted wisdom is a report published by HSBC Global Research last month that poured cold water on fears the nation is reaching an energy capacity crunch.

A combination of new gas-fired and renewable capacity, combined with slackening demand for power and a sharply falling oil price, is undermining the business case for the Hinkley C plant, HSBC argued.

In addition, within the next decade, the capacity of the interconnectors that link up the UK and continental European grids will have nearly trebled to 10GW. This increase means EU generators will be able to supply up to 20% of the UK’s electricity needs, which should also bring British energy prices closer in line with neighbouring countries.

The report predicts that by 2023, the scheduled date for Hinkley’s opening, the wholesale price of electricity will be half the £92.50 “strike price” that the government has guaranteed EDF will be paid for every MW per hour (MWh) of electricity generated at the Somerset plant.

Look to the future

Smith counters that HSBC’s “extremely short-sighted” conclusions “don’t take into account our aspiration to decarbonise generation,” explaining that demand for electricity will rise as road vehicles convert from fossil fuels.

He argues that current generating prices are artificially low. “A large proportion comes from plants built in the 1950s which were largely paid off in the 1970s so the cost of electricity at the moment is not real - it’s a legacy of the lack of investment and running old power stations into the ground,” he says.

In addition, Smith predicts that the cost of providing plants will fall for future projects, estimating a strike price of £80-85 per MWh will be achievable for the next two plants being built at Wylfa and Moorside by Hitachi and Westinghouse.

Richard Coackley, director of energy development at Aecom, also has concerns about the UK relying on other countries’ surplus energy pumped through the interconnectors.

“We can’t be reliant totally on external energy input and we need to contribute to others’ energy needs,” he says, noting that under current plans it is never anticipated that the interconnector would go the other way and export power.

And while gas and oil prices have recently plummeted, nuclear provision needs to be assessed over a much longer period than even the next decade, warns John Priestland, global strategy director at WSP. “It’s hard to comprehend how long term these projects are,” he says. “They are designed for 50 years with a potential extension of 40 so we are talking about technology that will still be generating next century. The short-term has very little relevance for a project that is so long-term.”

Nevertheless, Hinkley’s troubled delivery raises questions over whether such a crucially important piece of national infrastructure should be paid for by the private sector, which the UK is pioneering at the Somerset plant. In 2013 former Olympic Delivery Authority and Network Rail boss John Armitt argued the government should pay the up-front construction costs itself before selling the plant to the private sector.

Grimston says: “The heart of the problem is that we are trying to get private companies, or non-UK government companies, to carry out UK government policy in markets where they are focused on the bottom line. Markets in power are very good at sweating assets once you have built them by bringing costs of operation down quite effectively, but we are seeing that the markets are really awful at responding to the signals for new build when it is required.”

The private sector, left to its own devices, will opt for relatively low risk and cheaper technologies like combined cycle gas (CCG) plants, he adds. “To persuade people to do other than CCG requires massive financial inducements which result in costs looking on paper like those for Hinkley.”

Grimston argues that splitting out the operational and construction of the project would also cut building costs by minimising the risks involved in having to factor future energy price fluctuations into the contracts.

Going down this route, the government could still enter into risk-sharing arrangements with contractors to ensure that it is not saddled with the kind of cost overruns that have historically bedevilled the nuclear industry, he adds.

Coakley, who chairs the government’s nuclear construction best practice group, suggests it will be good for the industry to gain experience of the UK’s pioneering private sector procurement model, which is being looked at with interest by cash-strapped governments elsewhere. Anyway, Smith believes, effectively renationalising one part of the electricity supply mix would be deemed anti-competitive by those involved in other forms of generation.

More pressingly, any move to take new nuclear generation back onto the government’s balance sheet could open up further scrutiny at the European Court of whether its nuclear financing plans breach state aid rules, which the UK’s programme has recently been cleared of.

“If government were to change the model, it would spark another investigation and add further delay,” says the NIA’s Parker. “We don’t have the luxury of time because coal-fired stations are closing and there’s not much investment in gas fired.”

And Smith, who has worked in the atomic industry for 34 years, believes that work needs to begin soon to tap into the skills of those who built the last generation of nuclear power stations.

“Most of the people with experience of designing and constructing nuclear power stations are my age and older. If we don’t train a new generation of engineers we’ll have to effectively reinvent that skill from scratch and it will be much harder.

“I’m still hoping that I will be building nuclear power stations when I retire, but I’m 55 so the industry will have to get a move on.”

Timeline

January 2008: Labour government announces backing for new nuclear generation in its white paper

2011: National nuclear energy planning policy statement confirms Hinkley Point as site for new plants

October 2014: European Court rules that proposed funding formula, including Treasury-backed loan guarantee, doesn’t breach state aid rules

December 2014: EDF chief executive Vincent De Rivaz says Hinkley C funding deal should be complete by first quarter of 2015

January 2015: Parliament grants regulatory approval for Hinkley C

April 2015: EDF pauses Hinkley C preparatory works pending funding deal for the project

July 2015: EDF announces successful bidders for £1.3bn worth of contracts at Hinkley C

No comments yet