Many UK firms are owed money by Middle Eastern developers, but few are willing to talk about it. Roxane McMeeken spoke to one man who was prepared to break the silence

While it was growing, Dubai became a sort of surreal version of Las Vegas – the city that was one vast casino where everybody wins. It also acquired a casino’s reputation for style and taste, particularly in its nouveau riche architecture. This perception was meant to be challenged by the Dubai Arts District. Instead of all the “landmarks” of concrete, glass and steel, developer Abyaar wanted its £230m scheme to present a soulful appearance based on natural forms from the Arabian landscape, and it chose British architect Marks Barfield to design it.

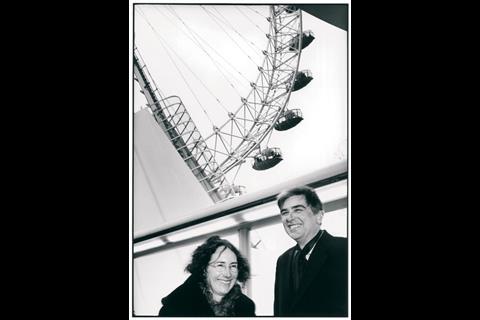

This looked like a shrewd choice. Although the practice was best known for the London Eye, it had designed a much praised cafe in Birmingham that took its shape from the golden spiral found in sunflowers and shells. For Abyaar, Marks Barfield created a design dominated by landscaping and parks that drew inspiration from pebbles and waves. Unfortunately, five months after the practice started work, Dubai turned into the casino where everybody loses.

David Marks, the co-founder of the firm, says Abyaar has not paid its invoices for the past 15 months. The present arrears are about £700,000, or 30% of Marks Barfield’s 2008 turnover, and the situation has reached crisis point. He is not suffering alone. The Association of Consulting Engineers (ACE) estimates that UK engineers are owed a total of £400m by clients in the Middle East, who are suffering severely from the global downturn, and most analysts think this is a fraction of the true figure. So far this year, Aukett Fitzroy Robinson, Arup, Atkins, Hyder, Interserve and WSP have indicated that they are facing payment problems in the Middle East. But the true size of the debts, and how overdue they are, has not emerged, largely because companies fear that going public about their problems will only antagonise clients in a region that hates to lose face.

Marks’ decision to tell his story will probably cross his name off many Dubai developers’ list. But he appears not to care: “I would think very hard about working in Dubai again; it has done us a lot of damage.”

Getting in

Marks Barfield began looking at Dubai seriously in early 2008. By that time the global financial crisis was tightening its grip on the UK, but the emirate appeared unscathed. Marks and his wife and business partner Julia Barfield were among the droves of Brits who thought it would be wise to bid for work there.

Marks says a trusted contact at a UK consultant put him in touch with Abyaar. Despite being founded in 2005, the firm was the eighth largest developer in Kuwait; now it was looking to expand in Dubai with three projects, for which it needed architects. Marks signed a contract with Abyaar in January last year to design the arts district as part of a wider 43 million ft2 “International Media Production Zone”, designed by RTKL, which was intended to attract media companies.

To begin with, all went to plan. “Abyaar was good at paying; it paid monthly in arrears and we were happy,” says Marks. Although most of the practice’s time was taken by the arts district, it began work on two other Abyaar schemes, the 2bn dirham (£336m) Acacia Avenue, in Dubai’s Jumeirah district, and another in Saudi Arabia.

Abyaar’s payments office wanted evidence that someone else within Abyaar had given us each order – it was ridiculous, but we provided it

David Marks

The first hint of trouble was in May 2008, when an interim payment was not made, but Marks put that down to Dubai’s notorious bureaucracy. Five months later, it still had not arrived, but Marks hoped for the best.

It was at this time that Building met him and Barfield in Dubai. These would turn out to be the last days of Dubai’s boom, although the only clues at the time were whispers about projects on hold and fewer deals being done at the Cityscape expo that month. By November it was clear that the property market had begun the collapse that (according to the latest figures from research firm Proleads) has halted work on projects worth $300bn (£182bn).

Back in October, Marks and Barfield wanted to tell Building about their design for the arts district. Their enthusiasm was obvious, as was the fact that theirs was a carefully conceived projects in a city known for brash designs that were built quickly and fairly difficult to live in. Marks explained that each of his 11 gently rounded buildings reflected a desert shade, from pinks through to yellows. The mainly residential buildings were ultramodern and traditional, with the deep balconies of traditional Arab architecture. At the centre was a clubhouse.

Marks was particularly excited about the scheme’s community feel. Some 80% of the development is parkland through which people can walk to the clubhouse, which includes a swimming pool and a spa. It was “really unusual” for Dubai, Marks said.

The descent

In November Marks received a warning he could not ignore: Abyaar told him to stop working on the project, which was by then under construction. He telephoned the developer’s chief operating officer and his practice manager rang its chief financial officer. “They both told us everything was fine,” says Marks.

As invoices continued to go unpaid, further calls to Abyaar revealed that it had moved its office for processing payments to Kuwait. “This meant we had to send all the documents we had sent to Dubai to Kuwait instead.” After this, what Marks calls “the whole payment plan circus” began. In one phone conversation, Marks says Abyaar asked him to offer a discount, but did not specify how much. Marks says he offered payment plans and discounts, including just under 19% of all that was owed, but the client “never agreed nor disagreed”, a response he alleges was a “delaying tactic”. “The value of the dirham had already fallen considerably,” he adds, “and I was becoming anxious about getting paid.”

But despite this concession, no money came through. Meanwhile, in January it was reported in the press that Abyaar had secured a loan worth 14m Kuwaiti dinars (£29.6m), which it told the Kuwait stock exchange was to pay off debts and fund projects. In February, it was reported that it had got a further 45m dinars. Marzouk Al Rashdan, Abyaar’s vice president, said the deal would reschedule “90% of Abyaar’s short-term finance”.

It will take two years for the case to get to court and then the settlement will leave you receiving 500 dirhams (£80) a year from us

What David Marks says Abyaar told him

By now Marks was fuming. “Abyaar got two injections of cash to help it pay its debts and we still weren’t getting paid.” As a result, the practice had its own financial crisis, and he and Barfield were forced to begin the gut-wrenching process of letting staff go. The payroll has now been cut from 40 to 20 people. Marks, who is not given to emotional statements, says: “It caused us a lot of pain.”

In April 2009, the whole drawn-out process became yet more tortuous, says Marks. “The people in Abyaar’s payments office wanted evidence that someone else within Abyaar had given us each order – it was ridiculous, but we provided it. Then they wanted us to get the project manager to justify each order. Next, they wanted to see copies of the work we had done. Then they wanted us to get the project manager to sign off each of these drawings – which became particularly difficult after the project manager has stopped working for Abyaar.”

Onerous as this was, Marks Barfield did it all. “We were able to justify everything. We actually found that we had duplicated one small invoice – an admin error that we were happy to correct.” But still no payments materialised. The whole “charade”, Marks claims, was aimed at “making us jump through hoops to hide the fact they had no intention of paying us”.

Maddeningly, in June, it was reported that Abyaar received yet another loan to meet its debts – a further 18m dinars. Yet Marks Barfield had still not received anything for invoices that dated back to May 2008.

The final straw came the same month when Abyaar called “implying we had to accept 50% or less and then they would consider paying us”. Marks refused to accept this. He claims that during one of many telephone conversations with Abyaar he was told “there is no point going to lawyers about this because we have the best lawyers working for us. It will take two years for the case to get to court and even then the settlement will leave you receiving 500 dirhams (£80) a year from us”. Abyaar was unavailable for comment on this claim.

At this point, Marks decided to hire a debt collection agency. He says: “We considered the legal route but I don’t trust the system in Dubai. The legal process is dysfunctional because the courts are backed up, and even if you get the judgment you want, that could take two years and then it’s doubtful it will be enforced. Plus, the clients can afford the best lawyers,” he says. So Marks has appointed a British debt collection firm. He says: “Their methods are completely legal but they are very persuasive.” Sinister as this may sound, he says it consists mainly of doggedly calling clients – something for which smaller firms don’t have the resources.

What now?

Some claim the situation in Dubai is starting to improve. Nelson Ogunshakin, chief executive of the ACE, says: “Discussions between clients and supply chains are moving forward.”

Contractors in Dubai have become glorified debt collectors. I’m spending all my time calling clients, asking when we’ll get paid

UK contractor in the UAE

A spokesperson for Atkins says although the Middle East remains “challenging”, “cash payments are being received”. The firm, which also works for Abyaar, would not comment on that developer specifically. Likewise, RTKL, the designer of the International Media Production Zone declined to comment.

Vince Clancy, the chief executive of Turner & Townsend, is also warily optimistic. “The Middle East has been tough but things are improving. We’ve rescheduled payments and although the situation is not fully resolved we’re getting there.”

Another hope is that the UK government may be able to influence the rulers of Dubai, who are closely linked to the main developers. Peter Mandelson, the business secretary, raised the payment issue on a visit to Dubai in April. The ACE says it wrote to Mandelson’s office recently and received an “encouraging reply”.

UK Trade & Investment, the arm of government that helps UK firms work abroad, also confirms it is talking to clients in Dubai. “We are in touch with a cross-section of UK construction sector companies that are operating in Dubai – engineering, architects, builders, small and large. We are speaking to Emirati entities too, and of course we have raised this with the government here.”

Marks Barfield, however, remains unpaid. July brought another twist of the knife when Abyaar announced a profit of 2009 of 4.89m Kuwaiti dinars (£10.4m) for the first half of 2009. This was down on the same period in 2008, when the client made 13.3m dinars, but it was profit all the same.

Others are also suffering. A source at a QS says his firm is owed about 35% of its turnover – about £30m – by Dubai developers. The source, who spoke on condition of anonymity, says: “We’re owed the equivalent of four months’ invoicing.” Those clients that are prepared to discuss payments are asking for discounts of up to 40%. “We can’t accept that. The situation is horrendous.”

Main contractors are affected, too. Although none would speak on the record, a senior source at one says: “Contractors in Dubai have become glorified debt collectors. I’m spending all my time calling clients, asking to go in and see them, asking when we’ll get paid or how much they can pay. Then I have to go back to subcontractors and divvy it up between the ones that are in the most need.” He says he tells them they will get the full amount eventually but that has not stopped many camping out in his reception.

Will the victims of the great Dubai meltdown ever see their money? A distant precedent is semi-feudal Saudi Arabia, which closed down its construction boom after the end of the seventies oil rush, leaving many British firms permanently unpaid. Dubai, by comparison, is a relatively open capitalist economy, and clients there will presumably have to play by the rules – eventually. But Marks is prepared for the worst. He says: “Whatever happens we will survive; we won’t go out of business. But this saga has taken up a lot of time and we have made a lot of redundancies, so it has caused us a lot of damage. We’re outraged by what has happened.”

Abyaar’s press office had not returned Building’s calls before the magazine went to press.

Don't miss the Global Infrastructure Forum

5 Readers' comments