Frank Gehry’s £28.5m Berlin concert hall is an unusual building for this celebrated creator of the unusual. Ike Ijeh finds that through its sharp contradictions of age, shape and material, it achieves a kind of peace

Frank Gehry’s latest European building is not quite what you might expect. Gehry is one of the world’s most famous architects and his buildings are widely recognised for their futuristic, deconstructionist design and their twisted, convoluted forms. But externally at least, his latest project features none of his trademark tortured choreography and is arguably his quietest work to date.

The Pierre Boulez Saal is a recently completed €34m (£28.5m) concert hall in Berlin. Located in the Mitte cultural quarter just south of Berlin’s thunderous domed cathedral and the Berlin State Opera House, it sits rather unassumingly on a quiet street corner. The project has left the exterior completely unchanged. What is now the Barenboim-Said Akademie, the building in which the new concert hall sits was built in 1955 as a repository for the nearby opera house. Unlike most of post-war Berlin, the building was faithful recreation of the bombed original with its rusticated base and stuccoed, classical facades carefully reconstructed.

Therefore the first surprise comes with the eventual realisation that whatever Gehry has done has been squeezed into the confines of a classical building, which one imagines would be largely unsympathetic to the shape-shifting histrionics he usually favours.

But this is not the first time Gehry has worked within a historic building. His Hejmdal medical centre in Aarhus, Denmark, his only project to date in Scandinavia, was also force-fed into a retained classical block; a jutting roof and leaning staircase the only outward signs of inner turmoil.

Equally, while Gehry designed the facades of his infamous DZ Bank building a stone’s throw away near the Brandenburg Gate (his only other Berlin building), the city’s strict planning codes meant that that exterior is almost mechanically sober while all the fun takes place in its extraordinary twisting vortex of an atrium.

So, as with both these projects, the scene here is set for an intriguing internal clash between old and new.

Gehry on the inside

Externally the building can read as three rectilinear volumes. A central, four-storey wing flanked by two symmetrical and slightly protruding three-storey wings. While the interior of the building has been almost entirely gutted, with just the external walls retained, this tripartite arrangement has been maintained internally and the plan too is split into three.

This simple layout is also something one might not expect to find on a Gehry scheme and is further evidence of the constraints the existing fabric imposed.

Of the three sections, the middle section has been reconfigured as a full-height entrance atrium featuring a small cafe and stair to one side and surrounded by balconies, all of which are surmounted by a large skylight. The western section of the building has been redeveloped as cellular administrative and rehearsal space for the Barenboim-Said Akademie, the music academy founded by Berlin State Opera music director Daniel Barenboim and close friend Edward W Said in 1999.

The new Pierre Boulez Saal Hall occupies the remaining eastern wing of the building and is the only part of the complex Gehry has designed. The foyer and academy accommodation were redeveloped by Berlin practice HG Merz.

The foyer and academy offer a calming sequence of warmly-lit and autumnally coloured contemporary spaces which, in their solidity and angularity, remain sympathetic to the architecture of the exterior. What is surprising are the frequent flashes of retained, rough industrial steelwork in the form of gantries, columns or sliding doors, reminders of the building’s modernist and utilitarian roots.

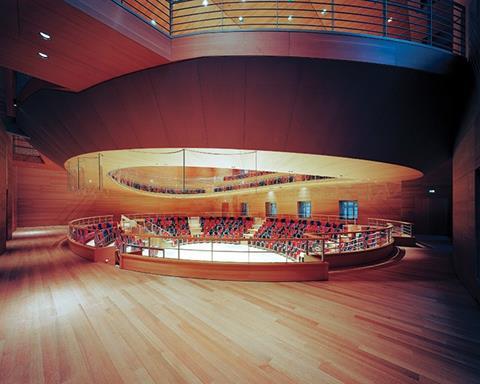

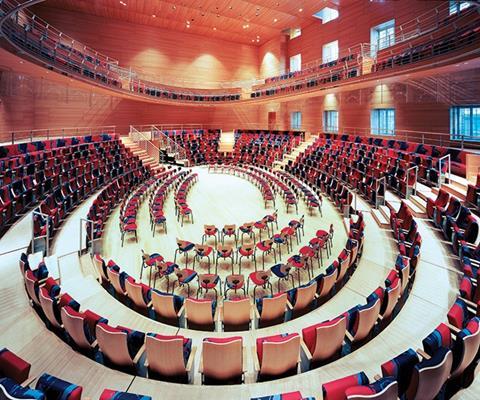

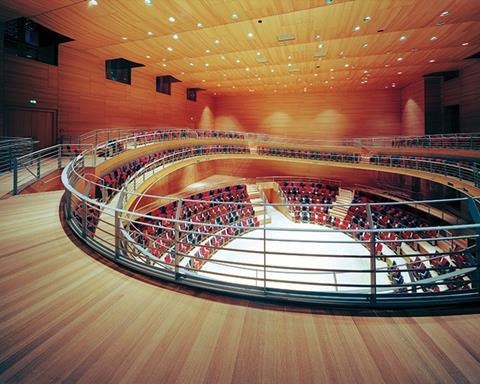

But the biggest surprise of all is Gehry’s new hall. It is a small space, seating a maximum of 682, but it is an extraordinary one. While the cuboid envelope formed by the building’s external walls is clearly visible, it is filled by a series of swirling ellipses like eddies frozen in a rectangular pool. In section the ellipses are spilt into two. The lowest forms a sunken stage surrounded by seating. The second forms a swooping balcony that encircles it above, its footprint slightly staggered from that of the oval below.

This may be a small space but it is full of tightly-spun drama and tension. The placing of an oval form within a rectilinear one provides the most obvious source of friction, the retention of the regimented window openings maintaining the conceit. Equally, in plan the upper balcony is expressed as an autonomous ribbon, pulling away from the corners of the enclosing cube to assist the passage of sound and create a dramatic quartet of plunging corner voids.

Gentle space

The space is undoubtedly small and intimate – the word “saal” is German for “room” – and the deliberate distinction between room and hall here is an important one to reveal the qualities to which this project aspires. And yet, in the separation of the upper balcony and the placement of one shape inside another, it calls to mind a football stadium cast in miniature, with the pitch reconfigured as an orchestral pit and the encircling stands buffed and pruned into an elegant timber promenade.

And it is timber that is the final crucial ingredient here. With the exception of the seats, every inch of the hall is clad in warm and luscious Douglas fir. It bathes the space in a comforting glow and suggests a level of intimacy and calm almost unmatched in Gehry’s previous work.

Gehry has placed a timber chamber into a building primarily comprised of another material before. His seminal Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles features the same ruse. But the swooping, vertiginous space he created there mimics the frenzy of its exterior form, even with the internal use of timber. But here the timber is a soothing agent, a balmy unction designed to repress discordancy rather than exaggerate it, like the muffles applied to quieten church bells.

The Pierre Boulez Saal Hall presents a Gehry we have rarely seen before. A calmer, more reflective and less provocative creator, not quite willing to entirely cast off the fissures and tensions from which he made his name but probably more engaged in trying to create harmony rather than chaos than we have ever seen him before.

Undoubtedly the presence of the existing building was a constraining factor here and in the hall one can almost sense the strain of the ellipses as they writhe and wriggle to burst free. But there are other factors too. Pierre Boulez, the celebrated French composer after whom the hall was named, died only last year and was a close friend of both Gehry and Barenboim. Gehry has spoken of the posthumous honour he wishes the hall to bestow and perhaps this softer tone has an emotional basis.

And in many ways the hall is a monument to contradiction, too. It negotiates a series of tensions between interior and exterior, classical and modern, cube and oval, timber and stone. And in so doing it seeks a consensus that is also at the core of the hall’s political ambitions. Daniel Barenboim is an Israeli and Edward W Said a Palestinian American. They founded the academy as part of their mission to unite young Arab and Israeli musicians. In its own resolution of smaller conflicts, the work stands as an architectural metaphor for bringing some harmony to some of the wider schisms of this world.

Project team: Concert hall

Architect Gehry Partners

Executive architect RW+

Client Pierre Boulez Saal / Barenboim-Said Akademie

Structural engineer GSE Ingenieur

Building services ZWP Ingenieur

Project manager TeamProject

No comments yet