Logging the details of the products and materials used on projects so they can have a second life after demolition has been discussed but never practised on a large London construction project – until now

Construction produces 68 million tonnes of demolition waste a year, 30% of the UK’s total. While 92% of this waste is recovered, most of it is downcycled to products of a lesser value. So reusing rather than downcycling materials could significantly reduce the industry’s carbon emissions.

As buildings become much more energy efficient and with the welcome focus on reducing upfront embodied carbon, the reuse of materials from demolished buildings is now the new front line for construction’s carbon reduction efforts. Forward-thinking developers are already reusing materials on projects to cut their carbon footprint – and this is a good marketing tool too.

Popular materials for reuse include structural steel and raised access flooring. Demand for the latter has become so great that anecdotally it is as expensive as new raised access flooring. This is because supply chains for reused materials are limited and the floor panels need to be cleaned up and tested before resale.

Reusing structural steel offers substantial carbon reductions, and establishing its properties is relatively easy through measurement and testing. Developers like identifying donor buildings because the new project can be designed specifically to suit the size of steel sections in the donor building. The limited supply of steel sections on the open market means that it is difficult to source the right sized sections to suit already designed buildings.

We saw there was a lack of standardisation about what data we record, how we record it and who is responsible for it. So, we developed the Waterman materials passport framework to standardise the process

Anastasia Stella, Circuland

For example, Great Portland Estates is developing what is said to be the largest steel reuse project in London at 30 Duke Street in St James’, an eight-storey office building with ground-floor retail south of Piccadilly. An estimated 74% of the structure will be reclaimed with 66.6% coming from the donor building, City Place House, a 40-year-old, 10-storey development close to Guildhall in the City, with the rest coming from steel reclamation specialists. Portland stone, granite, marble and timber handrails are also being reclaimed.

The market for reclaimed materials could receive a massive boost if the provenance – including the manufacturer, age, properties and standards to which it had been manufactured – can be easily established. The answer is material passports.

Information about building components is captured during design and construction and stored on a database, with the idea that this can be called up when the building is demolished, making it much easier to reuse the components.

The EU is already mandating digital product passports for items including electric car batteries from 2026 to make it easier to repurpose them for stationary applications such as home energy storage and – once the battery is worn out – for recycling. UK construction has some catching up to do as material passports have not been used on a major central London project… until now.

Barriers to their introduction include the lack of a standardised framework for the type of information that is captured and stored during design and construction so that consistent and relevant product data is available to those reusing those materials. A framework would stipulate the hierarchy of this information, from where the building is situated down to the properties of individual materials.

Engineer Waterman has developed just such a framework. It is providing building services, structural and sustainability services at 100 Fetter Lane, a 12-storey, 95,000ft2 office building that is targeting BREEAM Outstanding. Developer YardNine and funder BauMont Real Estate Capital have financed the project and the application of material passports on this scheme.

[The City of London] really have bought into material passports, and I think they eventually want to make it mandatory

Matt Brinklow, Mace

The framework was drawn up by Waterman’s sustainability specialist Anastasia Stella, who has since left the company to develop the software platform needed to record building and component data for recall later. “When we started, we saw there was a lack of standardisation about what data we record, how we record it and who is responsible for it”, she explains. “So, we developed the Waterman materials passport framework to standardise the process.

“Then we developed Circuland, which is a digital platform that brings the technology aspect into the framework. The framework provides the theory, and the platform brings the automation and practical application.”

Edenica, as the Fetter Lane project is called, is being used to trial the framework and digital platform. Mace is the main contractor.

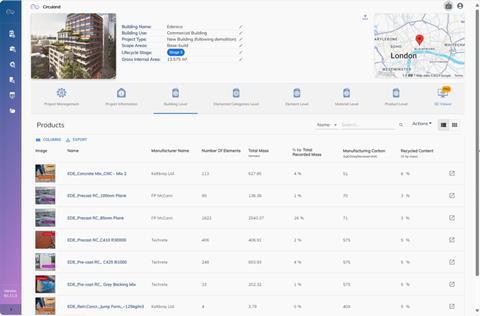

Five packages were chosen to trial the material passports: substructure and core, the steel frame, precast facades, raised access flooring and precast floor slabs. Those five packages add up to 80% of the building and the components do not need regular maintenance and are unlikely to deteriorate over the life of the building, making these easier to reuse.

The team avoided building services because of the complexity and maintenance regimes with most components replaced over the lifetime of the building. And providing warranties for mechanical components which wear out is more challenging than static pieces of steel.

Specialist contractor engagement was crucial, Stella says, as specialists are responsible for sourcing the materials and providing the relevant product information. Elliott Pycroft, project director for Mace, says this was the biggest challenge.

“We made sure that the supply chain was engaging as much as they needed to right from the beginning and altered the specifications while procuring those five packages to ensure that this was in line with what was needed, and the right data was there,” he says.

The building has been designed for disassembly; there are permanent lifting hooks at the back of the precast cladding panels and the steel structure is bolted, rather than welded.

Composite steel and concrete floor slabs have been avoided as these are impossible to reuse, with precast slabs selected instead. QR codes were fixed to the back of components to identify them when the building is deconstructed.

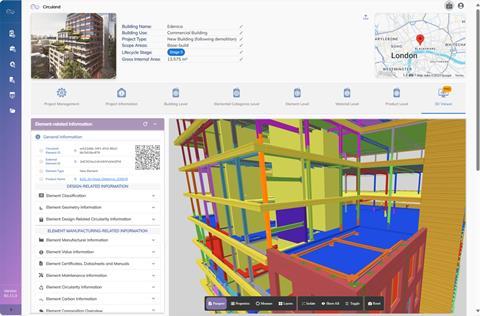

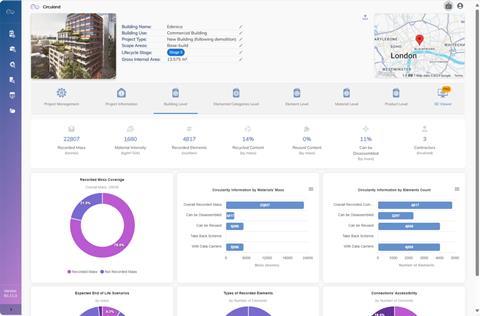

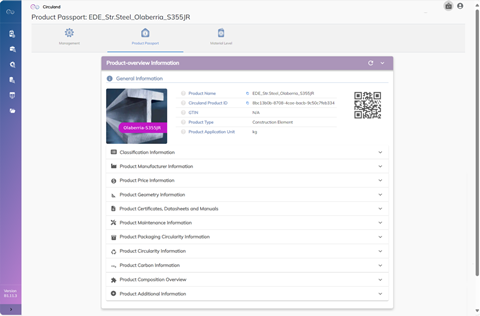

The materials and product information provided by the specialists was uploaded to the Circuland platform, which then generates a building passport and material passports for the components. The building passport is derived from the component passports and includes generic information such as the building’s location, the percentage of recycled content, what can be disassembled and the total carbon footprint.

The component passports provide a wealth of information including the manufacturer, geometric details, the standards to which the component was manufactured to, fire safety and CPD information, data sheets, maintenance requirements and the carbon footprint. It can also include the deconstruction strategy to help the demolition specialist.

Insitu concrete is hard to reuse but data was still captured including the grade of concrete, whether it included cement replacements and steel reinforcement details.

The platform hosts a 3D model of the building derived from the design and construction BIM data. Individual components can be selected by clicking on these in the model which brings up the passport information.

This avoids the need to identify the component from the QR code, which could be missing or damaged. Information about the components in the building can also be easily transferred to the facilities management team responsible for building maintenance. A maintenance history would make it easier to reuse some products.

The team are delighted with the results and plan to use it on other projects. Stella says feedback from the Edenica specialists suggests that the time needed to provide the necessary information could be reduced by 50%.

Pycroft says material passports are forming part of all the bids that Mace is putting forward for jobs while his colleague Matt Brinklow, Mace’s senior sustainability manager, says there is a lot of interest from the big London developers. The City of London Corporation is enthusiastic about material passports, Brinklow adds.

“The City of London was pioneering with their circular economy strategy and the need for a circular economy statement as part of a planning application,” he says. “They really have bought into material passports, and I think they eventually want to make it mandatory.”

Given the amount of development taking place across the Square Mile and the potentially enormous waste mountain and carbon emissions that this could generate, material passports are not before their time.

Project team

Client BauMont Real Estate Capital

Developer YardNine

Architect Fletcher Priest Architects

Cost consultant Arcadis

Project manager Third London Wall

Structural engineer Watermans Structures

Services engineer Watermans Building Services

Contractor Mace

Precast planks FP McCann

Precast façade Techrete

No comments yet