As high-street chains close stores around the country, companies that build shops are coming to terms with paused schemes and supply outstripping demand. But many forward-looking firms are exploring alternatives

It’s a bloodbath on the high street. This year has already seen Maplin, Toys R Us and House of Fraser collapse into administration, while the likes of Debenhams, Marks & Spencer and Mothercare have all announced big store closure programmes as profits tumble.

Traditional retailers are being hit by a perfect storm of fragile consumer confidence, big business rates rises and the accelerating shift to online consumption, with shoppers ever harder to prise from their sofas.

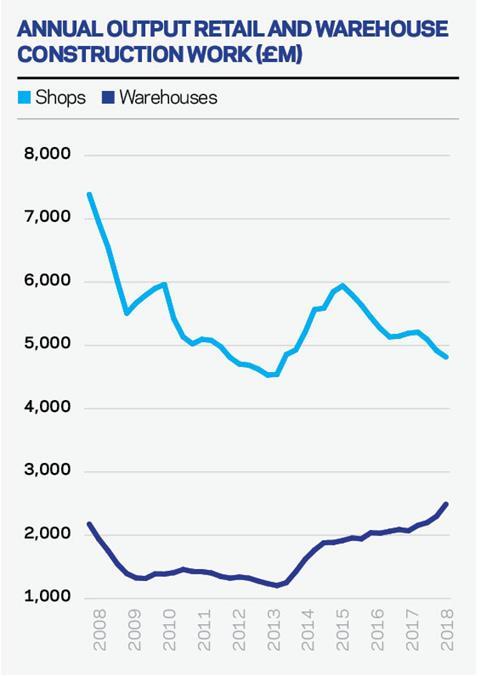

It should be no surprise this is having an impact on construction: Hammerson earlier this year took the decision to “defer” by at least six months its £1.4bn redevelopment of the Brent Cross shopping centre, while rumours of delay surround its similar-sized joint venture with Westfield in Croydon. With some declaring the age of the big shopping centre over, the annual volume of retail construction output has fallen by £1.1bn in three years, to £4.8bn in the 12 months to June this year, according to Office for National Statistics figures. That’s a drop of almost a quarter, once you take inflation into account.

“Retailers are taking stock. A lot of developers are in pause mode”

Daniel Hunt, Aecom

The problem, according to Mark Williams, director of shopping centre investor and asset manager Hark Group and president of the sector’s trade body, Revo, is space: there’s just too much of it. Williams estimates anything between 25-40% of all existing retail space in the UK will be surplus to requirements within a generation. Which doesn’t sound like good news for the people that build new retail space.

But there’s a flip side to this oversupply. If city centres are to survive, shops will have to be converted or redeveloped to into other more profitable uses. “You’ve got to go back to the Victorian period”, says Williams, “to find a time when the work to reposition our towns was of the scale it is now. It means changing every location in the UK.” The structural change in the way we all shop, therefore, provides opportunities as well as threats. Those in construction need to know, of course, exactly where those opportunities are going to be, and how the threats can be avoided.

Clearly negative

The reasons behind the retail sector’s travails are well-rehearsed. The proportion of goods bought online has increased five-fold in the last decade, with the Office for National Statistics stating that nearly 20% of purchases are now made online. Consumers use physical shops less often, and when they do venture outside, shopping must either be extremely convenient, or part of a day out where an attractive destination wraps entertainment and good food up with the experience. Clearly, many town centres, shopping centres and retail parks aren’t fit for this new era, leaving retailers losing sales to online-only rivals that are free of high street premises attracting expensive business rate bills.

The spate of insolvencies and retailers opting for company voluntary arrangements mean shopping centre owners are having to cope with falling rent rolls. Hammerson is the UK’s biggest shopping centre developer with £6bn of assets, and in its latest half-year results it reported that more than 5% of the space in its retail parks had fallen empty in just six months, mainly due to the collapse of Toys R Us, Maplin and Fabb Sofas. This saw rental income fall by 3.4%.

But even the retailers that, by most accounts, are managing the transition to online well, such as £4bn-turnover clothing and homeware company Next, are looking to reduce the space they hold and the rents they pay. The firm last week said it shut 15 stores this year, and that its average lease length is just six years.

Publishing half-year results, it made clear it had adopted strict criteria for its brick-and-mortar stores – it will renew store leases only where stores are either exceptionally profitable, or where it can get short leases at existing or reduced rent. Analyst house Exane BNP Paribas said the implications of its statement, which it described as “essential reading” for landlords, were that “reducing rents and shortening lease terms are clearly negative for valuations of retail property.”

At the same time as premises are becoming less profitable and valuable for landlords, the very fact of all the insolvencies and vacant space means that much of any demand for new space can be absorbed by vacant units. Simon Rawlinson, partner in consultant Arcadis, says: “It’s a tricky dynamic. There’s not many expanding, and losing retailers creates vacant units where you can bring new people in, cannibalising existing space.”

Thus, for those working exclusively in large, new-build retail developments, these are pretty desperate times. Despite the success of Westfield’s two big London developments at Stratford and White City, Daniel Hunt, director at consultant Aecom, says: “The days of the 1 million ft2 shopping centre – we’ll not see them again.” Hark Group’s Williams agrees. “If your specialism is building or designing three-level, inward-looking shopping centres and you’re not willing to learn new skills, you should probably retire now,” he says.

Even Robin Dobson, director of retail development at Hammerson – which is involved in the two biggest schemes currently in the UK pipeline, at Croydon and Brent Cross – admits that in future the construction of new “mega malls” is going to be “few and far between”.

Hammerson put the £1.4bn Brent Cross scheme – on which main contractor Laing O’Rourke had been expecting to start work – on hold in July citing “turbulence in the UK retail markets”. Dobson makes clear the developer is also taking the opportunity to review the scheme and potentially bring in more alternative uses. “We’re fully committed to it. But with the changes in the retail market, we’re reviewing how our plans need to change. This includes the weighting to retail as opposed to other uses,” he says.

He implies that the Croydon scheme, also, would not be starting on site any time soon. He says: “There are a number of other stages, not least progressing the detailed design work. It’s positive but complicated. There’s a long journey to take a project like this to site.”

This is a particular problem because Hammerson’s schemes are the biggest in the sector. Noble Francis, economics director at the Construction Products Association, says the body predicts retail construction output to fall 10% this year before stabilising in 2019 and 2020, with these two schemes the “key drivers” of this stabilisation. However, he says: “The retail environment could be very different next year and further delays cannot be ruled out.”

Darkest hour

Hammerson is of course not the only client to choose to pause during this market turbulence. Aecom’s Hunt says many retailers have reacted to the retailer insolvencies by commissioning detailed consumer research to help inform their next steps, and were unwilling to commit while this was still being digested. Meanwhile, Brexit has simply added to the uncertainty. “Retailers are taking stock. And a lot of developers are in pause mode. Rather than completely halting, they’re pausing for six months till they get over Brexit,” he says.

The darkest hour, however, is said to come just before the dawn. And for Hunt this shocked pause contains the promise of a coming opportunity. Indeed, for consultants, the pause itself has its compensations. “We’re doing a lot of feasibility work, optioneering for clients. This means getting projects up to certain stage, rather than going on site,” he says.

Hammerson: What developers want

Hammerson’s director of retail development Robin Dobson says there will be plenty of opportunities for retail construction if contractors and consultants are willing to keep up with new technology and remain flexible. “Fundamentally retailers will be needing to ensure they lead on innovation and maintain the maximum level of flexibility to adapt to consumer trends – whether that be in their technology or their physical buildings. Increasingly buildings will incorporate sophisticated artificial intelligence and voice recognition technology.

“The winners in the supply chain will be the ones that adapt to this change with relish and gusto.”

However, contractors will also need to keep working to bring construction costs down. “The ability for contractors to drive greater efficiency in programme, in cost and in quality – we want all of that, and ultimate flexibility at the same time.

“It’s a tough place to operate.”

Most agree the coming opportunity is in remodelling the existing stock – which means both big shop-fitting programmes for retailers, and phased rebuilding and adaption of shopping centres themselves. “Retailers want to find out what consumers want before going ahead,” says Hunt. “I think this [pause] is ahead of a significant programme of work.”

In fact, shopping centres have been adapting for some time, particularly by bringing in entertainment and food and beverage businesses to make shopping a genuine day out. But developers are now considering more radical options such as housing, office space and community facilities to generate footfall and intensity. “It’s about creating the best destination and experience,” says Hammerson’s Dobson. “We’re looking at a much more complementary mix of uses that deliver the hard data in terms of footfall that retailers want. It’s about how we repurpose, which means it’s actually a busy time for retail construction.”

Bright career

Hark Group’s Williams too is clear things are not all “doom and gloom.” “It’s about what we’re doing with that space. The environment has got to be nicer. If the places are ugly, people now have a choice, they don’t have to go out and shop.

“So if you know how to create flexible space, then you’ll have a bright career ahead of you.”

Experienced retail architect David Ellis, a member of Revo’s technical committee, says that in many towns the absolute centre still functions well, but the “doughnut” just around this faces the biggest challenges. “Often it’s about bringing residential closer in to the city centre, and looking closely about how you repurpose retail stock.

“We need to encourage social activity, gathering people together, civic and community uses. We’re social animals and that’s the role our city centres will continue to play.”

Some are already taking advantage of this new wave of opportunity. Kevin Dengate, retail head at contractor ISG says his firm will turn over £400m of retail work this year, a record figure, and that the negativity is overdone. “Frankly retailers have always historically gone out of business,” he says. “Nobody talks about the huge number of new online brands which are now starting to look for physical space.

“There’s always been new trends in the marketplace and contractors have to look at what’s next. There’s quite a big opportunity for older shopping centres to be improved with a mix of uses.”

ISG has also, Dengate says, taken advantage of existing relationships to deliver distribution and warehousing facilities for retailers’ online businesses (see box), mitigating declines in traditional retail build.

But if there are new opportunities, they will also require new approaches. Contracts are now, typically, for smaller £20m-60m phased redevelopments within live environments, rather than the likes of Laing O’Rourke’s rumoured £700m Brent Cross contract. These can, however, be more complex than the big one-off developments of old because of the risks associated with re-using existing buildings.

With construction costs calling schemes’ viability into question, however, clients can’t afford for contractors to simply price this additional risk and complexity in. This is leading to different contractual solutions. Architect Ellis says: “The repurposing is quite a tricky process and both the design industry and contractors need to deal with change and be flexible. You have to react to situations on site you’re not necessarily expecting.

“Hence the days of big lump sum design and build projects are gone, as contractors aren’t willing to take the risk. We’re seeing bespoke arrangements mixing design-and-build elements with construction management and other forms.”

ISG’s Dengate says this dynamic is manifesting in clients bringing contractors in earlier to work under pre-construction agreements in an open-book way, to mitigate risks before agreeing a final price. “Trying to get to a price point that works for the client and us isn’t always possible, and that’s where partnering comes in. We’re wanting to work in partnership to bring that risk down, we can offer much better value that way,” he says.

This, then, is fundamentally a challenge about remaking places – something that will give the UK’s designers and builders plenty of opportunities in the years to come – if they’re willing to be flexible about what they do, and how they do it.

Distribution – the flip side of the online revolution

Spend on distribution and warehousing construction has continued to grow in the last three years as retail construction output has dropped. At £2.5bn in the latest 12-month period, according to the Office for National Statistics, it is double what is was just five years ago. The growth in online shopping is a key driver, as retailers increasingly require large and sophisticated distribution facilities to handle online sales.

However, this is still only half as much as the £4.9bn spent on retail construction, and Noble Francis, economics director at the Construction Products Association, says: “The growth in warehouses construction is unlikely to offset the fall in new retail construction given that retail construction is higher value due to the interiors and fit-out.”

Nevertheless, Kevin Dengate, retail head at contractor ISG, says the firm has made construction distribution a major part of the firm’s retail construction business by leveraging existing relationships from shop-fitting programmes, and its own expertise from supermarket and data centre build work. “These buildings are now much more complicated than just sheds. It’s all about how quickly you can get to market – our customers come to us to get these built as quickly as possible,” he says.

1 Readers' comment